The Father [mellifluously]

Oh sir, you know well that life is full of infinite absurdities,

which, strangely enough, do not even need to appear plausible,

since they are true.

The Manager

What the devil is he talking about?

from: Six Characters in Search of an Author

by Luigi Pirandello (1921)

Harold Crick

This may sound like gibberish to you, but I think I’m in a tragedy.

from: Stranger Than Fiction (2006)

With apologies to those who get tired reading overly long posts, let’s get a little bit theological for a moment. I know I don’t have to ask you if you have ever considered what you would do if you were God (creator god, god of the universe, etc.). I’m sure you have at some point in your life. You have probably thought you would change the world, make it free of war and suffering, take away every tear and heal every wounded heart (I’m giving you/me the benefit of the doubt). And you would be doing good. Maybe, however, you have also considered what you would do if you were truly and completely a creature, that is, one who has a creator, a real being of some sort, not time+matter+chance. As a creature you would be contingent, that is, you would exist only because another being exists. You would breathe because another being gives you breath. You would awake each day because your creator gave you another day. And even your thoughts would be given to you by this creator or yours. Your creator would necessarily reside at a higher order of existence than you. In Medieval terminology, your creator would be more real than you. Compared to all of creation the creator God would be the most real being.

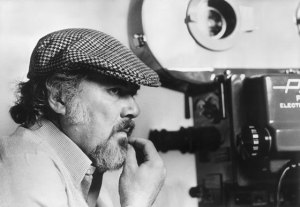

Heady stuff, but those are the kinds of ideas underlying the film Stranger Than Fiction (I am assuming you’ve seen the film), a film that explores the relationship between character and author. This is not a review of the film, but an exploration into its major theme.

When an author writes a novel, that author creates a world, a fictional world, but a world nonetheless. The characters in the novel are not real compared to you and me, but they are real compared to each other. They exist on a different, less real plane of existence than we do, but they are real (I realize this takes some mental gymnastics, but it makes sense, no really). If an author has a character killed in her novel she is not sent to jail, for that character is not real in comparison to us, but if that character has been murdered we readers want justice to be meted out within the context of the story. The author, also, is not beholden to the character. That character cannot legitimately hold the author accountable for anything.

But what if you were that character, and you had the knowledge of being that character, and therefore knew of your creator in some way? Maybe even got to meet your author? How would you feel then?

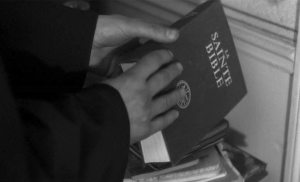

For centuries now there has been a passage (one of many, in fact) in the Christian New Testament scriptures that has driven Christians crazy. So much so that many (maybe most) Christians probably avoid it altogether. It goes like this:

But who are you, o man, to answer back to God? Will what is molded say to its molder, “Why have you made me thus?” Has the potter no right over the clay, to make out of the same lump one vessel for beauty and another for menial use?

The idea here is that a creator (here it is God, creator of everything) has complete decision-making control over the thing created, without impunity. Out of the same lump of clay a potter can make a beautiful vase for the mantle or a chamber pot for functional use. I do not know if there is a similar concept in other religions or worldviews. I grew up in a Christian tradition, so that’s what I know. Help me out if you know of any others. One thing I do believe is that we all (at least at times) tend to look at God, even if we don’t believe in a god, and deny God’s rule over us – certainly any kind of absolute rule. We sometimes also hold God (even if we don’t believe in a god) accountable for the state of the world, and may find ourselves saying that if we were God we would do things differently.

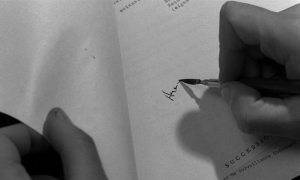

The issue, of course, is sovereignty. Who has ultimate control over your life? You, God, fate, nothing? In Stranger Than Fiction, Harold Crick (Will Ferrell) must come to terms with the fact that he is the literary creation of an author, that his existence is contingent upon the artistic desires of his author, Karen Eiffel (Emma Thompson). Now there are a host of unexplained issues, like how can Crick be a fictitious character interacting with the same world as his creator who should be on a different level of existence, etc., but the film doesn’t care to explain them. (I figure it’s like trying to figure out the implication of time travel in The Terminator films – at a certain point you just let it go.) For the most part, however, the film is not concerned with technicalities, but with the nature of contingency and authorship. The crux of the film comes when Crick finally reads the (his) story which has not yet been finished – the last few pages still handwritten, not yet typed, which would make them final and seal his fate. These last few pages are critical for Crick because they tell of his death. Crick has known he is going to die for part of the film already, and has been trying to avoid that, but now he reads what his author has planned for him and discovers his end.

Discovering the end of the story.

These are internal and sobering moments for Crick. By discovering the end of his story he has a context for his existence, he sees his purpose, his reason for being. Fortunately for him he reads of a noble end – dying saving the life of someone else. (What the film doesn’t explore is the possibility of him dying for not so noble reasons.) He is now no longer in the position of needing to know why he is here and where he is going. In this sense the film is fundamentally existential. The question of his existence is solved for him.

Now he gives the story back to his author, and surprisingly, he says that she should not change anything. In other words, it is the right thing for the story to end the way she has envisioned it, for him to die. She tries to protest, but he insists, and then walks away.

Thy will be done.

I cannot help but think of the moment, on the night before Jesus of Nazareth was killed by the Romans, when Jesus prays in the garden and confronts God the Father in his prayer. Now it would be wrong to make too much of the parallels, but in the story we find Jesus saying to God that he would prefer to not have to die, to not go through with it, but he then says whatever Gods wishes he himself also wishes. He says “Thy will be done.” For Crick, he has come to the conclusion that the story of his life, even if it entails him dying long “before his time” is okay with him. His words to his creator might just have well been, “Thy will be done.”

The intellectual doesn’t like it.

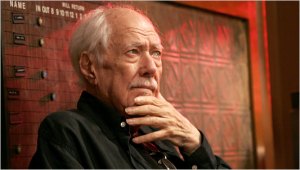

Interestingly, when the book is finished, and we follow Crick through what would have been the last moments of his life, we discover that his author has spared his life. Sure, Crick does save the boy from being hit by the bus, and Crick is then hit by the bus himself, but Crick lives. Badly banged up for sure, but alive nonetheless. Professor Jules Hilbert (Dustin Hoffman) does not like the new ending. He believes Crick’s death would make the book one of the best he has ever read, but now it’s just “okay.” Clearly, Hilbert is in a position to question the artistic choices of Eiffel, for he is an expert, a professor of literature. In some ways Hilbert stands for the tendency in all of us to look at the world and question the creator’s decisions.

“I mean, isn’t that the type of man you want to keep alive?”

When Hilbert asked why Eiffel changed the ending and kept Crick alive, she responds:

“Because it’s a book about a man who doesn’t know he’s about to die. And then dies. But if a man does know he’s about to die and dies anyway. Dies- dies willingly, knowing that he could stop it, then- I mean, isn’t that the type of man who you want to keep alive?”

Here we have the key line of the film. Crick’s destiny is changed because of a truly selfless act. He willingly laid down his life because he saw the true good of doing so. He sacrificed himself for the salvation of someone else, and because he knew that was what it was all about, that that was the telos of his life, he decided to choose what was good, not what was merely convenient for him. And then, because he was willing to be such a person his creator spares his life.

Harold Crick was a man in search of his author. Finding his author gave him the opportunity to know a little more about what his life was all about, He then had to choose whether to accept or reject his fate, to trust or reject his creator. Regardless, his fate was inevitably in the hands of his creator. He chose to accept it, not out of resignation, but out of the realization that his death was a good thing, really that his life had a purpose, was existentially valuable. He had a profound change of heart. And then he discovered that by accepting his fate he saved his life after all.

There are many accounts of human beings pleading with God. One such event was when God came to Moses and said he was so angry at the Israelites for turning their backs on him that he was going to destroy them all and start all over with Moses. Moses pleads with God to spare the Israelites and God does. But we also have the story above of Jesus pleading with God for another way and God does not spare him. It’s not about finding the right formula to effectively twist God’s arm to get what one wants. It’s about a true change of heart, a deep fundamental change at the core of one’s being, and then taking whatever comes. One may not be “happy” with what comes, but one might, just might find some level of contentment, as does Harold Crick.

What the film implies, but does not make explicit, is that for all his anxiety, Harold Crick is blessed. For most people the hardships and struggles of life come without explanation. We experience tragedy, or see others do so, without knowing what it is all about or if there is any purpose behind it. Crick gets to see his purpose. And when he does it makes sense to him, maybe not complete sense, but his life is not meaningless absurdity. This does not mean he is happy about it, but sometimes just knowing what it’s all about is all one needs. In fact, that might be what everyone desires after all – just to know what it’s all about.

I suppose that at some point all of us are faced with believing or not believing in a god. I grew up in a Christian tradition and have always believed in God. My theology has changed over the years (I’ll spare you the details), but I have always believed there is a purpose underlying my existence (and everyone else’s). This belief, though, has not made life easier for me. On the contrary, it has often made life harder, but better as well.