I am always a little curious about non-cinema art that gets labeled “cinematic.” A while ago I posted some thoughts on Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Still series. Lately I have been thinking about the staged photographs of Jeff Wall. And I have to say my thoughts are all a’flux.

If you are unfamiliar with Jeff Wall, one of the best overviews of Wall’s work is in this article.

Wall is one of the looming names in contemporary art, and like many artistic luminaries, one either likes his work or doesn’t. I happen to like his work quite a lot, but more from an intellectual curiosity and from being impressed with his virtuosity rather than from emotional engagement. In many ways his photographs seem to be either exercises in meticulous stagecraft or in meticulous banality. One label that has been tossed at Wall’s work is “cinematic” or “movie like.”

One article says the qualities of Wall’s photographs are such “…that the pictures glow like a movie screen.” The article goes on to say that Wall’s images are deeply indebted to cinema, which IS true, especially given that Wall wanted to be a filmmaker at one time. But is his work cinematic? [Other articles that mention the cinematic quality of Wall’s work: here, here, here, here, and here.]

I am inclined to think the label is being misused, but not intentionally so.

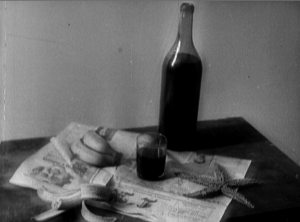

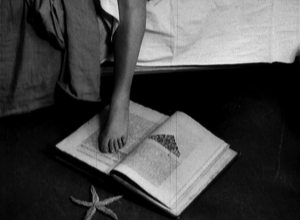

Consider the following four Jeff Wall images*:

Insomnia, (date ?)

Volunteer, (1996)

A View From An Apartment, (2004-2005)

Rear, 304 E. 20th Ave., May, (1997)

Each of these pictures are obviously staged and photographed with a great deal of control and specificity applied by the artist. And like any photograph with human beings in the frame, there is some sense of narrative. But can we call them cinematic? Is that fair? Is it because the pictures are of people in some kind of “life world” context? That is, do the images seem as though there is some preceding event(s) to the frozen moment, and that that frozen moment will be followed by another?

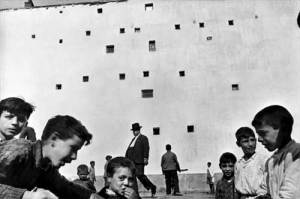

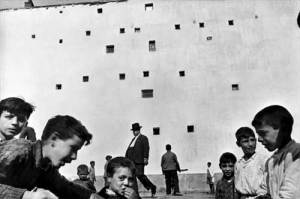

I do not think this is a strong enough argument for the cinematic label. But even if it is, aren’t there many more photographic examples that have richer narrative possibilities? Such as these two, apparently unstaged, photographs from Cartier-Bresson (I don’t have the titles or dates, unfortunately):

We could say much the same thing about a lot of painting. Consider this paining by Edgar Degas, which has a kind of in media res quality, as well as a sense of the banal.

Place de la Concorde, (1875), oil on canvas

Should we consider this Degas to be somewhat cinematic too? If so, then I find Degas to be at least as cinematic as Wall, and maybe more so, which is ironic given that the photographic apparatus is closer to that of cinema.

Maybe, instead, we should consider the typical way Wall’s images are presented to the viewer. Wall’s images are oversized (comparatively) cibachrome enlargements that are placed in lightboxes mounted on the wall. Thus, when one sees a Jeff Wall image in its native setting, one sees a very large photograph that is lit from behind, and therefore glows like a television screen, or, more appropriately, an advertisement light box. In this way Wall’s images have the immensity of a medium-large painting, but with the technical aura and aesthetic more closely aligned with mechanical presentation, i.e. television and cinema. Does that still qualify his work as cinematic? When one sees a lightbox advertisement at a bus stop or a store window does one think “cinematic?” Somehow I doubt it.

This video (below) of the Jeff Wall retrospective at MoMA will give some idea of how the images are presented.

http://www.youtube.com/get_player

Maybe it’s just the size of Wall’s work. Of course, great big narrative paintings have been around for a long time too. Maybe this painting at the Louvre is somewhat cinematic.

Note: I grabbed this image off the Internets. I don’t know the title or artist of the painting, and I don’t know who took the photo, but I’m sure it’s from someone’s vacation.

It certainly is huge and, although I don’t know its date, it must pre-date the invention of cinema. Does that mean it anticipates the coming of cinema in some way? Maybe, but not likely. Just because a work of art is big and appears to have a story embedded in it doesn’t automatically make it cinematic, seems to me. And, of course, the painting does not glow with its own light source. And yet, maybe it is cinema that is more like oversized genre paintings of the past and not the other way around. Should we label all instances of cinema as cinematic?(!).

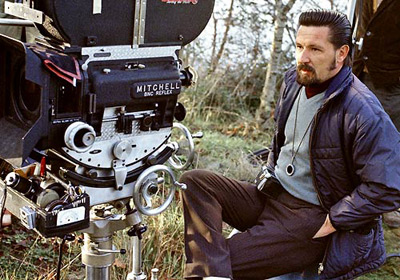

Maybe what is most fascinating about Jeff Wall’s work on an immediate level at least, is just how stagey they are. In the history of photography the staged photo has held a lesser place, reserved primarily for advertising, because staging an image apparently undercuts the great achievement of photography: capturing life in a moment, as it is (or was) with no barrier except for the lens and the technical processes. Wall, on the other hand, hires actors, carefully plans and sets up his shots, and probably takes numerous tries to get it just right. Then, of course, he digitally alters them as needed to get what he envisions.

Consider this image:

Mimic, (1982)

Here Wall has staged his re-imagined version of a real event which he saw. What hits the viewer, along with the obvious content of the subject, is the fact that this apparent “snapshot” could only exist if it was staged. It’s perfection, its clarity (only achieved with a not-very-portable large format camera sitting on a trip), its careful composition all point to a set-up rather than a lucky shot.

Maybe that staginess is what encourages the cinematic label. But that level of craft and arrangement is not unique to cinema. In most other arts the carefully arranged composition is standard fare. Just consider the genre paintings of Jan Steen:

The Artist’s Family, (c. 1663) Oil on canvas, Mauritshuis, The Hague

In this sense Wall’s work is something more akin to the history of art in general than to photography. The camera is his tool but he is not beholden to the “moment.”

Of course the staging of actors before the lens so that the camera can capture a scene, as it were, is nothing new. Although such staging has played a lesser role in the history of photography, as far as what is considered art is concerned, is has always been present, and maybe more prevalent in the past.

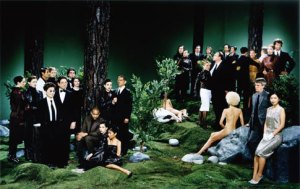

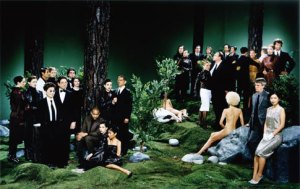

One connection with staging is the idea of the tableau vivant or living picture. Here we have the tableau vivant of Wall’s Dead Troops Talk:

Dead Troops Talk, (1992)

One of the comic ironies of this image is that we have those who are dead animating a tableau vivant. Now here we have an advertisement which appeared in the September 2000 issue of Harper’s Bazaar:

Here we have a tableau vivant from 1910 with actors portraying a scene from the story of Joan of Arc:

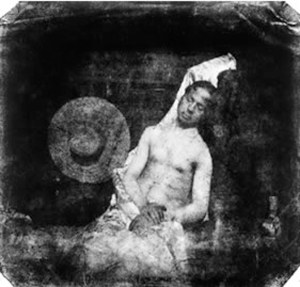

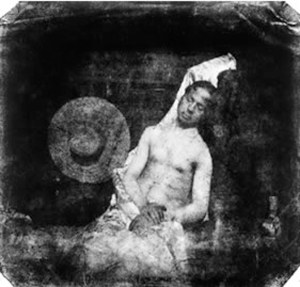

And here we have the photographer Hippolyte Bayard circa 1840 playing himself as a drowned man in a very early tableau vivant of sorts:

I find these kinds of connections fascinating, but nothing here suggests that Wall’s work is cinematic. In fact, the tableau vivant is more of a theater convention than that of cinema. Certainly Wall’s images have ties to photography, painting and theater that are at least as strong, and probably more so, than to cinema.

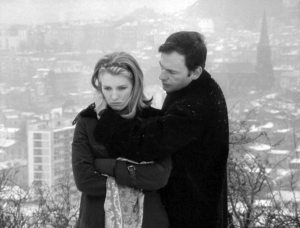

One thing to ponder is that some films do use tableaus to create their meanings. In other words, it is not uncommon for filmmakers to stage relatively static mise en scène for effect, rather than exploit the more cinematic capabilities of the technology. For example, consider these two images from Godard’s Weekend (1967):

Although the burning wrecks are dramatic, and the flames do move, the scenes are obviously carefully constructed piles of autos set aflame and presented to the viewer as a kind of emotional tableau on modernism – even humorous if one can see Godard winking.

Or consider these two images from Greenaway’s The Cook, The Thief, The Wife, and Her Lover (1989):

What makes tableau’s work in a cinema context is the fact that they are not cinematic in their qualities. There is something particularly “wrong” with them in the context that then draws our attention to their existence and therefore to our viewing.

And yet, though maybe not examples of the “cinematic,” what makes these images from Weekend and The Cook (et al) cinema is that, regardless of their tableau qualities, they exist in time and they have motion, and they are part of wholes that exist in time and have motion. Unlike the Jeff Wall images, these screengrabs are false images in a way, for the originals (and original intentions) are not of static moments, rather they move: the flames ascend, the steam rises, the camera pans and trucks.

And movement is the one thing photography lacks. But photography can suggest movement by capturing a thing in motion and presenting it as such. For example, this image:

Milk, (1984)

Here Wall has created a particularly enigmatic image of a man crouching on a sidewalk or path with milk shooting out of the bottle for some mysterious reason. At least one thing that makes this image interesting is the fact that the milk is in an impossible position. Liquid does not hang suspended in the air like that. Photography provides a unique ability to capture such images

But Wall also works on a grander scale with imaging movement. Consider this image:

A Sudden Gust of Wind, (1993)

I would consider A Sudden Gust of Wind to look the most like a still from some film, maybe an Eastern European film. But of course this image is not the progeny of cinema. It is a re-imaging of a famous Japanese print:

This print is from Hokusai’s 36 Views of Mount Fuji. Hokusai lived from 1760 to 1849, before the invention of cinema.

So even when we get close to something that might be cinematic there are specific non-cinema connection that pull us back. What then is cinematic? What are its qualities?

I am going to say that cinematic is a feeling more than a set of specific characteristics. The reason being that cinema has so many characteristics that a mere listing, and then tagging, would be an almost endless task. But feelings come from somewhere, are grounded in something, and I believe to feel that a work of non-cinema is cinematic must be based in some sense of what makes a movie a movie and not something else.

Cinema’s greatest strength lies with its unique abilities to manipulate the image in time and space. But it is important to realize that there are so many connections with other arts and with the varieties of human expertise that strict demarcations are impossible. Regardless, the cinematic image is an image that moves and that exists in time. One could add montage to the list, but one can find montage in all the arts – even Eisenstein argued for that. There is great power in the combination of film images, but “[t]he dominant, all-powerful factor of the film image is rhythm, expressing the course of time within the frame.” – Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time, p. 113.

But it is important to make a distinction. The time within the image is not the same as the time of the viewer even if they both tic off the same number of seconds. An artist creates a world and presents it to the viewer or reader. To receive the work is to enter into that world. With cinema one enters the image, as it were, and into the time of the story – into the world of the work. Cinema, unlike photography, can carry one along inside the image, inside the created world. The static photographic image, regardless of its qualities, can only go so far in this regard.

All arts create their worlds. What makes cinema cinematic is the ability to do so with greater power than other visual artforms, and in particular photography. Which brings us back to Jeff Wall.

There are aspects of Wall’s photographs that have kinship to cinema. But there is also a pushing back. The careful and obvious staginess, the frozen moment, the artificiality at times seem to undercut the cinematic label, even deny it. One may chaff at the mystery and long for more of a story, but Wall’s images, in that sense, are dead ends. Very quickly one realizes there really isn’t a story in the images because they are purely fabricated moments. They are not part of a rhythm. And thus, I see Wall’s works to be humorous in this regard: They draw one into an expectation of the cinematic but deliver something else. That something else is a mystery of Jeff Wall’s.

_____________________________________

*I have “screen grabbed” Jeff Wall’s images, except one, from the Jeff Wall Online Exhibition at the MoMA web site. Needless to say, the images here are not quite as good as they are on the MoMA site, and nothing compared to the real thing.