>

Stavrogin

…in the Apocalypse the angel swears that there’ll be no more time.

Kirillov

I know. It’s quite true, it’s said very clearly and exactly. When the whole of man has achieved happiness, there won’t be any time, because it won’t be needed. It’s perfectly true.

Stavrogin

Where will they put it then?

Kirillov

They won’t put it anywhere. Time isn’t a thing, it’s an idea. It’ll die out in the mind.

-F. Dostoievsky, The Possessed

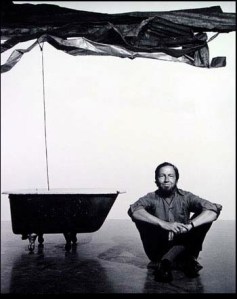

There are few filmmakers, if any, who have philosophized as deeply about the nature of time as Andrey Tarkovsky. Time, as a philosophical concept, has been examined in depth by many, but rarely do filmmakers seem to step, philosophically or artistically, beyond commonly accepted film school concepts of time. In other words, for most filmmakers time is a concrete conceptual medium which one manipulates with accepted narrative forms according to common schemata in order to tell a clearly defined and easily understood cause and effect story. But that is not really time itself.

from Stalker (1979)

What do we talk about when we talk about time? For the most part we talk of time’s effects, of managing time, of the past or the future, of what could have happened or what did, of how one thing led to another. But time is none of these things in itself. Time is a mystery, and we relate to time in ways far more complex than the march of cause and effect. When we bring in the relationship of memory to time, and we dig into the nature of reality and its relationship to truth, we begin to exponentially expand the concept of time. Because memory is related to morality, time can also be understood as a spiritual concept.

from Mirror (1975)

In his book Sculpting in Time (pp. 57-8), Tarkovsky says this about time:

Time is necessary to man, so that, made flesh, he may be able to realize himself as a personality. But I am not thinking of linear time, meaning the possibility of getting something done, performing some action. The action is a result, and what I am considering is the cause which makes man incarnate in a moral sense.

History is still not Time; nor is it evolution. They are both consequences. Time is a state: the flame in which there lives the salamander of the human soul.

Time and memory merge into each other; they are like the two side of a medal. It is obvious enough that without Time, memory cannot exist either. But memory is something so complex that no list of all its attributes could define the totality of the impressions through which it affects us. Memory is a spiritual concept! For instance, if somebody tells us of this impressions of childhood, we can say with certainty that we shall have enough material in our hands to form a complete picture of that person. Bereft of memory, a person becomes the prisoner of an illusory existence; falling out of time he is unable to seize his own link with the outside world–in other words he is doomed to madness.

As a moral being, man is endowed with memory which sows in him a sense of dissatisfaction. It makes us vulnerable, subject to pain.

Cinema has a unique relationship with time. Of all the art forms only film can capture time, as it were, and preserve it. Tarkovsky says this as critical. Here he talks of this unique aspect of cinema around the time of filming The Sacrifice (1986):

His speech begins at 5:37 into the piece.

To think of time as a state, as that flame in the soul, and of action as merely a result of time, and to think of cinema as a medium that preserves time, provides the foundation upon which a different kind of film can be constructed. Different, not in the sense of odd or misshapen, but different from the conventions and expectations of what we have typically received. The history of cinema is replete with action driven plots, with stories that emerge from a fascination with time’s results, the effects of time. When the underlying state of time is manifest, if at all, it is too often the representation of shrunken persons and truncated souls.

from Nostalgia (1983)

What then is the role, even responsibility of cinema? Or of the filmmaker? The role of cinema has necessarily changed over the years. In years past the mere existence of a short film brought about wonderment, and sometimes caused viewers to run for the exits. But cinema has changed, and so have we. Tarkovsky writes:

Cinema is therefore evolving, its form becoming more complex, its arguments deeper; it is exploring questions which bring together widely divergent people with different histories, contrasting characters and dissimilar temperaments. One can no longer imagine a unanimous reaction to even the least controversial artistic work, however profound, vivid or talented. The collective consciousness propagated by the new socialist ideology has been forced by the pressures of real life to give way to personal self-awareness. The opportunity is now there for filmmaker and audience to engage in constructive and purposeful dialogue of the kind that both sides desire and need. The two are united by common interests and inclinations, closeness of attitude, even kinship. Without these things even the most interesting individuals are in danger of boring each other, of arousing antipathy or mutual irritation. That is normal; it is obvious that even the classics do not occupy an identical place in each person’s subjective experience.

Sculpting in Time (pp. 84-85)

Tarkovsky goes on to say about the filmmaker’s responsibility:

Directing in the cinema is literally being able to ‘separate light from darkness and dry land from the waters’. The director’s power is such that it can create the illusion for him of being a kind of demiurge; hence the grave temptations of his profession, which can lead him very far in the wrong direction. Here we are face with the question of the tremendous responsibility, peculiar to cinema, and almost ‘capital’ in its implications, which the director has to bear. His experience is conveyed to the audience graphically and immediately, with photographic precision, so that the audience’s emotions become akin to those of a witness, if not actually of an author.

Sculpting in Time (p. 177)

from The Sacrifice (1986)

In a sense the filmmaker is the creator of time. The audience enters into the world of the film, the mental/emotional space circumscribed by the filmmaker, and lives, as it were, in that space for at least the duration of screen time, if not on some level for ever after. Clearly this has implications for issues of responsibility, both for filmmaker and audience. But this kind of thinking opens up possibilities for ‘approach’ as well. In other words, to think of time as “the cause which makes man incarnate in a moral sense” is to confront something living rather than a mere object of manipulation. This approach is what turns Tarkovsky’s film into what they are: films that contemplate the deeper truths of the soul and call us to do the same. This approach is also the antidote to the ‘boring art film’ in that it does not allow for the mere application of style for artistic effect. And it can, at times, be as a kind of lens that helps reveal the more profound aspects of one’s soul.

*All quotes come from Sculpting in Time by Andrey Tarkovsky, trans. Kitty Hunter-Blair, University of Texas Press, 1986.