I first published this post in 2012, just one year before I officially converted to the Catholic Church. My journey up to that point had included a possible conversion to Eastern Orthodoxy but I first had to sort out my thinking on the Pope. This post was a piece of that process.

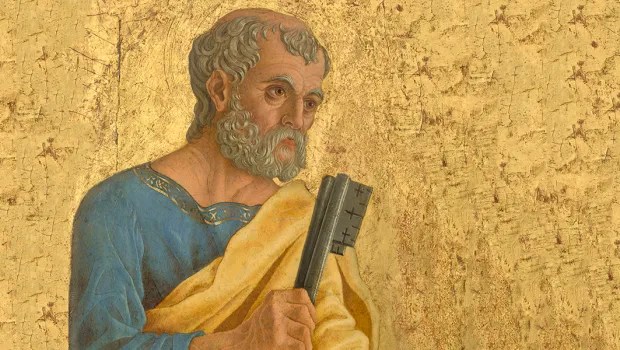

The Apostle Peter is a fascinating man in the New Testament. In the Protestant world it is common for pastors to say they love Peter because he was such a goof-up. Peter gives us all kinds of hope that any of us can be saved. But anyone who has grown up in, or spent a lot of time in, the Protestant world and worldview knows it is Paul who is Apostle number one. There are at least two good reasons for this. One is that Paul wrote those books of the Bible that are most central for Protestants: Romans, Galatians, 1 Corinthians, etc. Second is that Protestants are wary of Peter because Catholics say the true Church founded by Christ was founded upon Peter (the rock) as the first of the apostles, as the first “pope”. Get too close to Peter and one might be tempted to think Catholics are on to something.

But Peter is a big deal. To my count Peter is mentioned in the New Testament something like 155 times, whereas the rest of the apostles combined are only mentioned around 130 times. Of course mere numbers don’t necessarily add up to importance. It’s how Peter is mentioned, what he does, what he says, what others say about him, and especially what Christ says to Peter that show Peter is the central Apostle, the key figure of the New Testament Church. As we look at the Biblical references to Peter the picture begins to fill out.

An aside: I have heard many Protestant teachings on the famous Matthew 16:18 passage where Jesus says “upon this rock I will build My church.” That passage in isolation can be taken any number of ways. But after looking at a more complete picture of Peter as the New Testament writers saw him, I must say the Roman Catholic understanding of Peter as the Rock upon which Christ will build His Church makes the most sense. In fact, even without this particular passage, the other passages below add up to the same idea. Rather than seeing the Catholic position as some kind of crazy overlay to this passage, it now seems clear to me that it is the Protestants who must come up with a better argument. So far I have not heard anything better. Of course, this makes me, an old Protestant, very curious.

Below are the New Testament references I was able to find regarding Peter. I have tried to group them a bit, and added a few of my thoughts. I have not ranked them in any particular order. I’m sure I’ve made some mistakes. All quotations are from the New American Standard Bible.

Peter listed/mentioned first with the apostles

Peter being mentioned or listed first among the apostles:

Matt. 10:2 Now the names of the twelve apostles are these: The first, Simon, who is called Peter, and Andrew his brother; and James the son of Zebedee, and John his brother;

Mark 1:36 Simon and his companions searched for Him;

Mark 3:16 And He appointed the twelve: Simon (to whom He gave the name Peter),

Luke 6:14-16 Simon, whom He also named Peter, and Andrew his brother; and James and John; and Philip and Bartholomew; and Matthew and Thomas; James the son of Alphaeus, and Simon who was called the Zealot; Judas the son of James, and Judas Iscariot, who became a traitor.

Acts 2:37 Now when they heard this, they were pierced to the heart, and said to Peter and the rest of the apostles, “Brethren, what shall we do?”

Acts 5:29 But Peter and the apostles answered, “ We must obey God rather than men.

Peter is first when entering upper room after our Lord’s ascension:

Acts 1:13 When they had entered the city, they went up to the upper room where they were staying; that is, Peter and John and James and Andrew, Philip and Thomas, Bartholomew and Matthew, James the son of Alphaeus, and Simon the Zealot, and Judas the son of James.

Peter leads the fishing and his net does not break. According to Catholics, the boat (the “barque of Peter”) is seen as a metaphor for the Church:

John 21:2-3 Simon Peter, and Thomas called Didymus, and Nathanael of Cana in Galilee, and the sons of Zebedee, and two others of His disciples were together. Simon Peter said to them, “I am going fishing.” They said to him, “We will also come with you.” They went out and got into the boat; and that night they caught nothing.

John 21:11 Simon Peter went up and drew the net to land, full of large fish, a hundred and fifty-three; and although there were so many, the net was not torn.

Though Peter and John are both very important figures in the early church, Peter is always mentioned before John:

Luke 8:51 When He came to the house, He did not allow anyone to enter with Him, except Peter and John and James, and the girl’s father and mother.

Luke 9:28 Some eight days after these sayings, He took along Peter and John and James, and went up on the mountain to pray.

Luke 22:8 And Jesus sent Peter and John, saying, “Go and prepare the Passover for us, so that we may eat it.”

Acts 1:13 When they had entered the city, they went up to the upper room where they were staying; that is, Peter and John and James and Andrew, Philip and Thomas, Bartholomew and Matthew, James the son of Alphaeus, and Simon the Zealot, and Judas the son of James.

Acts 3:1-4 Now Peter and John were going up to the temple at the ninth hour, the hour of prayer. And a man who had been lame from his mother’s womb was being carried along, whom they used to set down every day at the gate of the temple which is called Beautiful, in order to beg alms of those who were entering the temple. When he saw Peter and John about to go into the temple, he began asking to receive alms. But Peter, along with John, fixed his gaze on him and said, “Look at us!”

Acts 3:3 When he saw Peter and John about to go into the temple, he began asking to receive alms.

Acts 3:11 While he was clinging to Peter and John, all the people ran together to them at the so-called portico of Solomon, full of amazement.

Acts 4:13 Now as they observed the confidence of Peter and John and understood that they were uneducated and untrained men, they were amazed, and began to recognize them as having been with Jesus.

Acts 4:19 But Peter and John answered and said to them, “ Whether it is right in the sight of God to give heed to you rather than to God, you be the judge;

Acts 8:14 Now when the apostles in Jerusalem heard that Samaria had received the word of God, they sent them Peter and John,

Peter is mentioned first as going to mountain of transfiguration. He is also the only disciple to speak at the transfiguration:

Luke 9:28 Some eight days after these sayings, He took along Peter and John and James, and went up on the mountain to pray.

Luke 9:33 And as these were leaving Him, Peter said to Jesus, “ Master, it is good for us to be here; let us make three tabernacles: one for You, and one for Moses, and one for Elijah”— not realizing what he was saying.

Peter is the first of the apostles to confess the divinity of Christ:

Matt. 16:16 Simon Peter answered, “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.”

Mark 8:29 And He continued by questioning them, “But who do you say that I am?” Peter answered and said to Him, “You are the Christ.”

John 6:69 We have believed and have come to know that You are the Holy One of God.”

Peter ranked(?) higher than John

John arrived at the tomb first but stopped and waited for Peter. Peter then arrived and entered the tomb first:

Luke 24:12 But Peter got up and ran to the tomb; stooping and looking in, he saw the linen wrappings only; and he went away to his home, marveling at what had happened.

John 20:4-6 The two were running together; and the other disciple ran ahead faster than Peter and came to the tomb first; and stooping and looking in, he saw the linen wrappings lying there; but he did not go in. And so Simon Peter also came, following him, and entered the tomb; and he saw the linen wrappings lying there,

It is Peter that is named as the eye witness even though both Peter and John had seen the risen Jesus the previous hour:

Luke 24:34 saying, “ The Lord has really risen and has appeared to Simon.”

Peter seen as the Leader of the Apostles

In the garden of Gethsemane, Jesus asks Peter, and no one else, why he was asleep. It would seem Peter is held accountable, on behalf of the apostles, for their actions:

Mark 14:37 And He came and found them sleeping, and said to Peter, “Simon, are you asleep? Could you not keep watch for one hour?

Peter is designated (called out) by an angel as unique among the apostles:

Mark 16:7 But go, tell His disciples and Peter, ‘ He is going ahead of you to Galilee; there you will see Him, just as He told you.’”

Peter receiving Special Instruction and Revelation

Peter alone is told he has received special, divine revelation from God the Father:

Matt. 16:17 And Jesus said to him, “Blessed are you, Simon Barjona, because flesh and blood did not reveal this to you, but My Father who is in heaven.

Jesus instructs the disciples by specifically instructing Peter to let down their nets for a catch. Peter specifically is told he will be a “fisher of men”:

Luke 5:4,10 When He had finished speaking, He said to Simon, “Put out into the deep water and let down your nets for a catch… and so also were James and John, sons of Zebedee, who were partners with Simon. And Jesus said to Simon, “ Do not fear, from now on you will be catching men.”

Peter speaking/Asking on Behalf of the Disciples

Peter asks Jesus about the rule of forgiveness. Peter frequently takes a leadership role among the apostles in seeking understanding of Jesus’ teachings:

Matt. 18:21 Then Peter came and said to Him, “Lord, how often shall my brother sin against me and I forgive him? Up to seven times?”

Peter speaks on behalf of the apostles by telling Jesus that they have left everything to follow Him:

Matt. 19:27 Then Peter said to Him, “Behold, we have left everything and followed You; what then will there be for us?”

Peter speaks for the disciples on their following Jesus:

Mark 10:28 Peter began to say to Him, “Behold, we have left everything and followed You.”

Peter speaks for the disciples about their witnessing Jesus’ curse on the fig tree:

Mark 11:21 Being reminded, Peter said to Him, “ Rabbi, look, the fig tree which You cursed has withered.”

Peter functions as the spokesman or representative (or vicar, to use popular a Catholic term) for Jesus:

Matt. 17:24-25 When they came to Capernaum, those who collected the two-drachma tax came to Peter and said, “Does your teacher not pay the two-drachma tax?” He *said, “Yes.” And when he came into the house, Jesus spoke to him first, saying, “What do you think, Simon? From whom do the kings of the earth collect customs or poll-tax, from their sons or from strangers?”

When Jesus asked who touched His garment, it is Peter who answers:

Luke 8:45 And Jesus said, “Who is the one who touched Me?” And while they were all denying it, Peter said, “Master, the people are crowding and pressing in on You.”

It is Peter who seeks clarification of a parable on behalf on the disciples:

Luke 12:41 Peter said, “Lord, are You addressing this parable to us, or to everyone else as well?”

After many of the disciples leave Jesus, it is Peter who speaks on behalf of the remaining disciples and confesses their belief in Christ after the Eucharistic discourse:

John 6:68 Simon Peter answered Him, “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have words of eternal life.

Peter as Christ’s Representative on Earth

Protestants debate this, but it would seems that Jesus builds the Church primarily (only?) on Peter, the rock:

Matt. 16:18 I also say to you that you are Peter, and upon this rock I will build My church; and the gates of Hades will not overpower it.

Only Peter receives the keys of the kingdom of heaven:

Matt. 16:19 I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; and whatever you bind on earth shall have been bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall have been loosed in heaven.”

Peter, by paying the tax for both Jesus and himself, is acting Christ’s “representative” on earth:

Matt. 17:26-27 When Peter said, “From strangers,” Jesus said to him, “Then the sons are exempt. However, so that we do not offend them, go to the sea and throw in a hook, and take the first fish that comes up; and when you open its mouth, you will find a shekel. Take that and give it to them for you and Me.”

Peter given charge/care of the other disciples

Jesus prays specifically for Peter, that his faith may not fail, and charges him to strengthen the rest of the apostles:

Luke 22:31-32 “Simon, Simon, behold, Satan has demanded permission to sift you like wheat; but I have prayed for you, that your faith may not fail; and you, when once you have turned again, strengthen your brothers.”

In front of the apostles, Jesus asks Peter if he loves Jesus “more than these,” which likely refers to the other apostles. Peter has a special role regarding the apostles:

John 21:15 So when they had finished breakfast, Jesus said to Simon Peter, “Simon, son of John, do you love Me more than these?” He said to Him, “Yes, Lord; You know that I love You.” He said to him, “Tend My lambs.”

Jesus charges Peter to “feed my lambs,” “tend my sheep,” “feed my sheep.” Sheep appears to mean all people (or all believers), including the apostles:

John 21:15-17 So when they had finished breakfast, Jesus said to Simon Peter, “Simon, son of John, do you love Me more than these?” He *said to Him, “Yes, Lord; You know that I love You.” He said to him, “Tend My lambs.” He said to him again a second time, “Simon, son of John, do you love Me?” He said to Him, “Yes, Lord; You know that I love You.” He said to him, “ Shepherd My sheep.” He said to him the third time, “Simon, son of John, do you love Me?” Peter was grieved because He said to him the third time, “Do you love Me?” And he said to Him, “Lord, You know all things; You know that I love You.” Jesus said to him, “ Tend My sheep.

Peter Leading the Early Church

Peter initiates the selection of a successor to Judas immediately after Jesus ascended into heaven. Note: This passage also supports (or establishes) the concept of apostolic succession:

Acts 1:15 At this time Peter stood up in the midst of the brethren (a gathering of about one hundred and twenty persons was there together), and said,

Peter is the first apostle to preach the Gospel:

Acts 2:14 But Peter, taking his stand with the eleven, raised his voice and declared to them: “Men of Judea and all you who live in Jerusalem, let this be known to you and give heed to my words.

Peter is the first to preach on repentance and baptism in the name of Jesus Christ:

Acts 2:38 Peter said to them, “ Repent, and each of you be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins; and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit.

Peter performs the first healing miracle of the apostles:

Acts 3:6-7 But Peter said, “I do not possess silver and gold, but what I do have I give to you: In the name of Jesus Christ the Nazarene—walk!” And seizing him by the right hand, he raised him up; and immediately his feet and his ankles were strengthened.

Peter is the first to teach that there is no salvation other than through Christ:

Acts 3:12-26 But when Peter saw this, he replied to the people, “Men of Israel, why are you amazed at this, or why do you gaze at us, as if by our own power or piety we had made him walk? The God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, the God of our fathers, has glorified His servant Jesus, the one whom you delivered and disowned in the presence of Pilate, when he had decided to release Him. But you disowned the Holy and Righteous One and asked for a murderer to be granted to you, but put to death the Prince of life, the one whom God raised from the dead, a fact to which we are witnesses. And on the basis of faith in His name, it is the name of Jesus which has strengthened this man whom you see and know; and the faith which comes through Him has given him this perfect health in the presence of you all. And now, brethren, I know that you acted in ignorance, just as your rulers did also. But the things which God announced beforehand by the mouth of all the prophets, that His Christ would suffer, He has thus fulfilled. Therefore repent and return, so that your sins may be wiped away, in order that times of refreshing may come from the presence of the Lord; and that He may send Jesus, the Christ appointed for you, whom heaven must receive until the period of restoration of all things about which God spoke by the mouth of His holy prophets from ancient time. Moses said, ‘ The Lord God will raise up for you a prophet like me from your brethren; to Him you shall give heed to everything He says to you. And it will be that every soul that does not heed that prophet shall be utterly destroyed from among the people.’ And likewise, all the prophets who have spoken, from Samuel and his successors onward, also announced these days. It is you who are the sons of the prophets and of the covenant which God made with your fathers, saying to Abraham, ‘ And in your seed all the families of the earth shall be blessed.’ For you first, God raised up His Servant and sent Him to bless you by turning every one of you from your wicked ways.”

Acts 4:8-12 Then Peter, filled with the Holy Spirit, said to them, “Rulers and elders of the people, if we are on trial today for a benefit done to a sick man, as to how this man has been made well, let it be known to all of you and to all the people of Israel, that by the name of Jesus Christ the Nazarene, whom you crucified, whom God raised from the dead—by this name this man stands here before you in good health. He is the stone which was rejected by you, the builders, but which became the chief corner stone. And there is salvation in no one else; for there is no other name under heaven that has been given among men by which we must be saved.”

Peter resolves the first doctrinal issue on circumcision at the Church’s first council at Jerusalem, and no one questions him. After Peter the Papa spoke, all were kept silent:

Acts 15:7-12 After there had been much debate, Peter stood up and said to them, “Brethren, you know that in the early days God made a choice among you, that by my mouth the Gentiles would hear the word of the gospel and believe. And God, who knows the heart, testified to them giving them the Holy Spirit, just as He also did to us; and He made no distinction between us and them, cleansing their hearts by faith. Now therefore why do you put God to the test by placing upon the neck of the disciples a yoke which neither our fathers nor we have been able to bear? But we believe that we are saved through the grace of the Lord Jesus, in the same way as they also are.” All the people kept silent, and they were listening to Barnabas and Paul as they were relating what signs and wonders God had done through them among the Gentiles.

Only after Peter finishes speaking do Paul and Barnabas speak in support of Peter’s definitive teaching:

Acts 15:12 All the people kept silent, and they were listening to Barnabas and Paul as they were relating what signs and wonders God had done through them among the Gentiles.

The church prayed for Peter while he was in prison:

Acts 12:5 So Peter was kept in the prison, but prayer for him was being made fervently by the church to God.

Peter acts as the chief elder (or bishop?) by exhorting all the other elders of the Church:

1 Peter 5:1 Therefore, I exhort the elders among you, as your fellow elder and witness of the sufferings of Christ, and a partaker also of the glory that is to be revealed,

Peter brings the Gospel to the Gentiles

Peter is first Apostle to teach that salvation is for all, both Jews and Gentiles:

Acts 10:34-48 Opening his mouth, Peter said: “I most certainly understand now that God is not one to show partiality, but in every nation the man who fears Him and does what is right is welcome to Him. The word which He sent to the sons of Israel, preaching peace through Jesus Christ (He is Lord of all)— you yourselves know the thing which took place throughout all Judea, starting from Galilee, after the baptism which John proclaimed. You know of Jesus of Nazareth, how God anointed Him with the Holy Spirit and with power, and how He went about doing good and healing all who were oppressed by the devil, for God was with Him. We are witnesses of all the things He did both in the land of the Jews and in Jerusalem. They also put Him to death by hanging Him on a cross. God raised Him up on the third day and granted that He become visible, not to all the people, but to witnesses who were chosen beforehand by God, that is, to us who ate and drank with Him after He arose from the dead. And He ordered us to preach to the people, and solemnly to testify that this is the One who has been appointed by God as Judge of the living and the dead. Of Him all the prophets bear witness that through His name everyone who believes in Him receives forgiveness of sins.” While Peter was still speaking these words, the Holy Spirit fell upon all those who were listening to the message. All the circumcised believers who came with Peter were amazed, because the gift of the Holy Spirit had been poured out on the Gentiles also. For they were hearing them speaking with tongues and exalting God. Then Peter answered, “ Surely no one can refuse the water for these to be baptized who have received the Holy Spirit just as we did, can he?” And he ordered them to be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ. Then they asked him to stay on for a few days.

Acts 11:1-18 Now the apostles and the brethren who were throughout Judea heard that the Gentiles also had received the word of God. And when Peter came up to Jerusalem, those who were circumcised took issue with him, saying, “ You went to uncircumcised men and ate with them.” But Peter began speaking and proceeded to explain to them in orderly sequence, saying, “ I was in the city of Joppa praying; and in a trance I saw a vision, an object coming down like a great sheet lowered by four corners from the sky; and it came right down to me, and when I had fixed my gaze on it and was observing it I saw the four-footed animals of the earth and the wild beasts and the crawling creatures and the birds of the air. I also heard a voice saying to me, ‘Get up, Peter; kill and eat.’ But I said, ‘By no means, Lord, for nothing unholy or unclean has ever entered my mouth.’ But a voice from heaven answered a second time, ‘ What God has cleansed, no longer consider unholy.’ This happened three times, and everything was drawn back up into the sky. And behold, at that moment three men appeared at the house in which we were staying, having been sent to me from Caesarea. The Spirit told me to go with them [m] without misgivings. These six brethren also went with me and we entered the man’s house. And he reported to us how he had seen the angel standing in his house, and saying, ‘Send to Joppa and have Simon, who is also called Peter, brought here; and he will speak words to you by which you will be saved, you and all your household.’ And as I began to speak, the Holy Spirit fell upon them just as He did upon us at the beginning. And I remembered the word of the Lord, how He used to say, ‘ John baptized with water, but you will be baptized with the Holy Spirit.’ Therefore if God gave to them the same gift as He gave to us also after believing in the Lord Jesus Christ, who was I that I could stand in God’s way?” When they heard this, they quieted down and glorified God, saying, “Well then, God has granted to the Gentiles also the repentance that leads to life.”

Peter binds and looses

Peter exercises his binding authority by declaring the first anathema of Ananias and Sapphira (which is ratified by God):

Acts 5:3 But Peter said, “Ananias, why has Satan filled your heart to lie to the Holy Spirit and to keep back some of the price of the land?

Peter again exercises his binding and loosing authority by casting judgment on Simon’s quest for gaining authority through the laying on of hands:

Acts 8:20-23 But Peter said to him, “May your silver perish with you, because you thought you could obtain the gift of God with money! You have no part or portion in this matter, for your heart is not right before God. Therefore repent of this wickedness of yours, and pray the Lord that, if possible, the intention of your heart may be forgiven you. For I see that you are in the gall of bitterness and in the bondage of iniquity.”

Peter heals others

Peter’s own shadow has healing power:

Acts 5:15 to such an extent that they even carried the sick out into the streets and laid them on cots and pallets, so that when Peter came by at least his shadow might fall on any one of them.

Peter is mentioned first among the apostles and works the healing of Aeneas:

Acts 9:32-34 Now as Peter was traveling through all those regions, he came down also to the saints who lived at Lydda. There he found a man named Aeneas, who had been bedridden eight years, for he was paralyzed. Peter said to him, “Aeneas, Jesus Christ heals you; get up and make your bed.” Immediately he got up.

Peter is mentioned first among the apostles and raises Tabitha from the dead:

Acts 9:38-40 Since Lydda was near Joppa, the disciples, having heard that Peter was there, sent two men to him, imploring him, “Do not delay in coming to us.” So Peter arose and went with them. When he arrived, they brought him into the upper room; and all the widows stood beside him, weeping and showing all the tunics and garments that Dorcas used to make while she was with them. But Peter sent them all out and knelt down and prayed, and turning to the body, he said, “ Tabitha, arise.” And she opened her eyes, and when she saw Peter, she sat up.

Angels are active in Peter’s life and ministry

Cornelius is told by an angel to call upon Peter. Peter was granted this divine vision:

Acts 10:5 Now dispatch some men to Joppa and send for a man named Simon, who is also called Peter;

Peter is freed from jail by an angel. He is the first Apostle to receive direct divine intervention:

Acts 12:6-11 On the very night when Herod was about to bring him forward, Peter was sleeping between two soldiers, bound with two chains, and guards in front of the door were watching over the prison. And behold, an angel of the Lord suddenly appeared and a light shone in the cell; and he struck Peter’s side and woke him up, saying, “Get up quickly.” And his chains fell off his hands. And the angel said to him, “Gird yourself and put on your sandals.” And he did so. And he said to him, “Wrap your cloak around you and follow me.” And he went out and continued to follow, and he did not know that what was being done by the angel was real, but thought he was seeing a vision. When they had passed the first and second guard, they came to the iron gate that leads into the city, which opened for them by itself; and they went out and went along one street, and immediately the angel departed from him. When Peter came to himself, he said, “Now I know for sure that the Lord has sent forth His angel and rescued me from the hand of Herod and from all that the Jewish people were expecting.”

Other Apostles Testify to Peter’s Teaching and Leadership

James speaks to acknowledge Peter’s definitive teaching. “Simeon” is a reference to Peter:

Acts 15:13-14 After they had stopped speaking, James answered, saying, “Brethren, listen to me. Simeon has related how God first concerned Himself about taking from among the Gentiles a people for His name.

Paul says he doesn’t want to build on “another man’s foundation” which may refer to Peter and the church Peter may have built in Rome:

Rom. 15:20 And thus I aspired to preach the gospel, not where Christ was already named, so that I would not build on another man’s foundation;

Paul distinguishes Peter from the rest of the apostles and brethren:

1 Cor. 9:5 Do we not have a right to take along a believing wife, even as the rest of the apostles and the brothers of the Lord and Cephas?

Paul distinguishes Jesus’ post-resurrection appearances to Peter from those of the other apostles:

1 Cor. 15:4-8 and that He was buried, and that He was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, and that He appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. After that He appeared to more than five hundred brethren at one time, most of whom remain until now, but some have fallen asleep; then He appeared to James, then to all the apostles; and last of all, as to one untimely born, He appeared to me also.

Paul spends fifteen days with Peter privately before beginning his ministry. This comes even after Christ’s revelation to Paul. Paul needed Peter’s acceptance and blessing:

Gal. 1:18 Then three years later I went up to Jerusalem to become acquainted with Cephas, and stayed with him fifteen days.

Interesting

Peter is the only man to walk on water other than Christ:

Matt. 14:28-29 Peter said to Him, “Lord, if it is You, command me to come to You on the water.” And He said, “Come!” And Peter got out of the boat, and walked on the water and came toward Jesus.

Jesus teaches from Peter’s boat. The boat may be a metaphor for the Church, the so-called “barque of Peter”:

Luke 5:3 And He got into one of the boats, which was Simon’s, and asked him to put out a little way from the land. And He sat down and began teaching the people from the boat.

Peter speaks out to the Lord in front of the apostles concerning the washing of feet:

John 13:6-9 So He came to Simon Peter. He said to Him, “Lord, do You wash my feet?” Jesus answered and said to him, “What I do you do not realize now, but you will understand hereafter.” Peter said to Him, “Never shall You wash my feet!” Jesus answered him, “ If I do not wash you, you have no part with Me.” Simon Peter *said to Him, “Lord, then wash not only my feet, but also my hands and my head.”

Only Peter got out of the boat and ran to the shore to meet Jesus:

John 21:7 Therefore that disciple whom Jesus loved said to Peter, “It is the Lord.” So when Simon Peter heard that it was the Lord, he put his outer garment on (for he was stripped for work), and threw himself into the sea.

Jesus predicts Peter’s death:

John 13:36 Simon Peter said to Him, “Lord, where are You going?” Jesus answered, “ Where I go, you cannot follow Me now; but you will follow later.”

John 21:18 Truly, truly, I say to you, when you were younger, you used to gird yourself and walk wherever you wished; but when you grow old, you will stretch out your hands and someone else will gird you, and bring you where you do not wish to go.”

Peter is mentioned first in conferring the sacrament of confirmation:

Acts 8:14 Now when the apostles in Jerusalem heard that Samaria had received the word of God, they sent them Peter and John,

Peter was most likely in Rome. “Babylon” was often used as a code word for Rome:

1 Peter 5:13 She who is in Babylon, chosen together with you, sends you greetings, and so does my son, Mark.

Peter writes about Jesus’ prediction of Peter’s death:

2 Peter 1:14 knowing that the laying aside of my earthly dwelling is imminent, as also our Lord Jesus Christ has made clear to me.

Peter makes a judgement of Paul’s letters:

2 Peter 3:16 as also in all his letters, speaking in them of these things, in which are some things hard to understand, which the untaught and unstable distort, as they do also the rest of the Scriptures, to their own destruction.

Peter was the first among the Apostles, perhaps struggled with that position at times, but proved to be the servant of all:

Matt. 23:11 But the greatest among you shall be your servant.

Mark 9:35 Sitting down, He called the twelve and *said to them, “ If anyone wants to be first, he shall be last of all and servant of all.”

Mark 10:44 and whoever wishes to be first among you shall be slave of all.