[In this post I ruminate on the relationship of art to our belief, or absence of belief, in God, god, or gods. As is typical for me, my train of thought is more lurching than steady, and my end goal is more personal than pedagogical.]

Our lenses

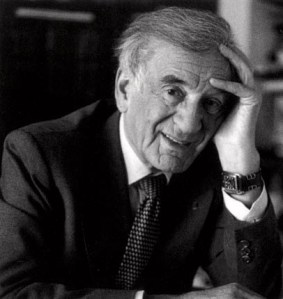

I love Pasolini’s seminal filmIl Vangelo secondo Matteo (1964). It is a work of great and simple beauty. It is also a powerful film that flies in the face of the overly sentimentalized and often lifeless versions of Jesus’ life that came before. And yet, Pasolini, though he seems to be taking the story directly from the words on the page (the Gospel of St. Matthew), understands Christ through his own political and personal commitments. In other words, Pasolini, the devout Marxist, unabashed homosexual, and hater of the Catholic Church, saw a Christ that was thoroughly materialist (philosophically) and politically radical (of the socialist ilk).

An earthy, socialist Christ

Enrique Irazoqui as Jesus

from Il Vangelo secondo Matteo (1964)

As I understand it, for Pasolini, Jesus was a kind of pre-incarnate Karl Marx (rather than the incarnate God) who challenged the status quo of his day, and died as the earliest socialist martyr. Pasolini’s belief in the non-existence of God played a big part in how he saw Jesus and why he made the film. In a sense one could say Il Vangelo secondo Matteo is a kind of materialist corrective to the church’s position.

As I said, I love Pasolini’s film, but he got it wrong. I say this because of my own beliefs about God and about Jesus which, though personal on the one hand, I believe are also objectively true. My understanding of God is integral to the set of the “lenses” through which I look at the world. In other words, the difference between me and Pasolini is not really about any of his films, rather our differences go back to our presuppositions about God, truth, and the goals of human existence – even if we may agree on many things, and no doubt I am generally in awe of him as an artist.

Certainly great works of art are not, in our experience, predicated on any particular belief about God.

The God Who Is There

I have been thinking lately (and off and on for a long time) of the role that theology plays, or does not play, in how one approaches watching a film, looking at a painting, listening to a piece of music, or reading a book. So much of what we get out of a work of art comes from what we are able to bring to it, especially what it is we want from that particular work of art, and of art in general. What we want, I believe, is deeply affected by, and even grows out of, whether or not we are convinced of the existence of God, or god, or many gods, or none at all. So much depends on whether we are convinced of some ultimate meaning in the Universe, or whether we believe there is no ultimate meaning. And so much depends on how honest, even ruthlessly honest, we are with ourselves about these issues and their implications.

I use the word theology specifically. The term “theology” is a compound of two Greek words, θεος (theos: god) and λογος (logos: rational utterance). What I am interested in is a reasoned and rational examination of God, not merely of some vague spirituality (but that’s another presupposition isn’t it). What I find critical is the blunt question: Do you (do I) believe in God? How one answers that question has profound implications.

But the question is already on the table. We have inherited it. We can’t get away from it, just as we can’t get away from a myriad of other questions. And how we live our lives, including the art we make, is directly related to our answer. Art is a part of how we live our lives and, in many ways, emerges from the very heart of the matter. This is as true for Pasolini as it is for Spielberg as it is for Tarantino.

Often a work of art has, embedded within it, the answer to the question. Sometimes that answer is obvious. More often the answer is like backstory, a kind of presupposition that sits in the background and informs the art out front, as it were.

Moral Objects

A work of art is, in some ways, a mysterious thing. Like love, we know what art is, but we can’t always nail it down and give it a clear definition and well defined boundaries. Art emerges from deep within our humanness. Every culture and society has organically produced art, that is, art which emerges naturally from withing that culture or society. When I was an art history major many years ago I was introduced to many ancient works of art, via slides of course, like this exciting number:

Seated female, Halaf; 7th–6th millennium B.C., Mesopotamia or Syria

Ceramic, paint; H. 5.1 cm, W. 4.5 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art

This little statuette dates from nearly nine thousand years ago. Most likely it is a symbol of fertility. And most likely it was part of the symbolic rites and proto-religious system of that time. Many thousands of figures like this one have been unearthed. This little object speaks volumes about what was important to that ancient culture, like the importance of fertility to agrarian societies, and the importance of sexuality, and the very human need to supplicate before a god for one’s well-being. It also speaks of the human tendency to create symbols and to understand the world in terms of abstractions.

What I find interesting is how ancient and deeply ingrained is the human need to grasp at metaphysical solutions to the everyday muck of life problems, fears, and desires. I also find it fascinating that humans have to make physical objects that express the metaphysical, the ontological, the teleological, etc.

Even the Israelites, who had seen the ten plagues on Egypt, who had witnessed the parting of the Red Sea, who had the pillar of fire and the pillar of smoke in the wilderness, who had seen the walls of Jericho miraculously fall, and who had seen many other wonders of Yahweh, still created the golden calf, and still kept idols of other gods in their houses, and still built or maintained the high places (religious sites on hilltops to worship gods other than Yahweh). Today we have our idols and gods too – witness the way we worship our sports teams, or entertainers, our possessions, ourselves, for example.

Moral Stories

What humans have always seemed to enjoy are stories of moral dilemmas played out in both mundane and fantastical ways. Consider the medieval mystery plays. These were more than merely pedagogical in nature, they were social events that brought people together and incorporated some audience participation, including talking back to the characters during the performance, etc.

I hear that in some movie theaters in other countries (I write from the U.S.) audiences are very vocal and even talk to the screen, as it were, and critique out loud the actions of the characters while the film is playing. Regardless, quiet or vocal, we all seem to gravitate toward the moral. We like passing judgment, we like justice, and, interestingly, we like wickedness too. However, without some kind of absolute from which morality emanates, having a moral opinion is, in final terms, as much comic as it is tragic.

Medieval Mystery Play

So why do we continue to hold moral positions in a morally relativistic and credulistic world? If I had a clear answer I could probably chair some philosophy or psychology department somewhere. My guess, though, is that we will invent an absolute if we can’t find one. In other words, if one doesn’t believe in moral absolutes, or in something big enough (God for example), then one will invent a substitute absolute, for example: an economic or political system, or a biological and physical set of laws, or maybe an absolute that claims there are no absolutes. Regardless, the moral story still digs deep into our souls.

Even the most mundane and vapid kinds of films have some moral content which can be understood within a larger framework of meaning. Consider this audio review of the recent film Tranformers by a pastor at Mars Hill Church in Seattle. (The review is at the end of that post.)

Only Physical, or Metaphysical?

As I take a look at the popular art of today, that is, television shows (i.e. CSI, Survivor, et al) and film (i.e. Michael Clayton, Enchanted, et al), I see worlds presented that do not include God, or any so-called traditional god, that is, a creator deity with whom our destiny lies. These are materialistic worlds, worlds in which stuff is the ultimate reality, no final truth, and no source of meaning. Interestingly, the goals of the characters are all about meaning, and soul searching, and truth.

The characters or contestants are driven forward by things or ideas that they deem important. This is basic story telling. This is fundamental script writing. But it doesn’t make sense if there is no final meaning in the universe, otherwise it’s just a cruel game. Why should we care that someone is searching for something that doesn’t exist? Or even if, for some untenable reason, we do care, why should they search? Consider this quote regarding the modern predicament:

The quality of modern life seemed ever equivocal. Spectacular empowerment was countered by a widespread sense of anxious helplessness. Profound moral and aesthetic sensitivity confronted horrific cruelty and waste. The price of technology’s accelerating advance grew ever higher. And in the background of every pleasure and every achievement loomed humanity’s unprecedented vulnerability. Under the West’s direction and impetus, modern man had burst forward and outward, with tremendous centrifugal force, complexity, variety, and speed. And yet it appeared he had driven himself into a terrestrial nightmare and a spiritual wasteland, a fierce constriction, a seemingly irresolvable predicament.

~Richard Tarnas, The Passion of the Western Mind

What does one do with this? How does one come to terms with a spiritual wasteland, or an irresolvable predicament? Is it so that rational human beings must suffer the conflict of a great desire for meaning in a world that has no ultimate meaning? Is religion an answer or a placebo? No matter what we do we do not get away from these questions. How we solve them, or come to terms with them, is a big deal (or maybe it is also meaningless). My contention is that there is a God, that that God is there, and that that God is knowable. But am I deluded? I don’t think so. And the person who thinks I am deluded believes from a place of conviction as well. I find this more than fascinating.

Michael Clayton

What most recently sparked my thinking about all this God and art stuff was a recent viewing of Michael Clayton. The story in this film plays itself out in a Western (geographically & conceptually), materialistic world where there is no transcendent god. It is a thoroughly modern view of human existence. There are no moral absolutes. And yet, Clayton is a man in search of himself. He is in desperate need of a positive existential moment. He needs to make a self-defining, self-actualizing choice so that he can move beyond his cliff-edge existence and become who he should be. He needs to make the right choice even if it is difficult and painful, even if it means giving up who he has been. There is nothing narratively original in this aspect of the story. It is as timeless as a Greek tragedy.

The story revolves around a legal battle in which a company is being sued for its harmful actions. Arthur Edens (Tom Wilkinson) is the attorney working the case. Unfortunately for his law firm and for his client he is deeply troubled by the case. He feels he is defending murder, in a sense. The firm sends Michael Clayton (George Clooney) to talk with Edens. Part of that conversation goes like this:

Michael Clayton: You are the senior litigating partner of one of the largest, most respected law firms in the world. You are a legend.

Arthur Edens: I’m an accomplice!

Michael Clayton: You’re a manic-depressive!

Arthur Edens: I am Shiva, the god of death

“I am Shiva, the god of death.”

Wow. Where did that come from? Shiva, the god of death? It certainly grabs one’s attention, and it sounds rather cool, but why, in this film, out of nowhere make a reference to one of the principal deities of Hinduism? I say “nowhere” because there is no indication throughout the film that any of the characters believe in any kind of god or religion. In fact, it could be argued that the problem facing all the characters is that, because there is no god, no ultimate reality to which they are finally accountable, they are lost in a sea of moral floundering. Morality becomes personal preference, personal conviction, and power.

Making a reference to Shiva, the destroyer and transformer Hindu god, makes some sense then. First, Edens feels like a destroyer, or at least one who defends the destroyer. He has personal convictions of wrongdoing and it is eating away his soul. Second, in a world personal morality one can choose, as one needs or sees fit, any god that works for the moment, so why not Shiva? Shiva becomes Eden’s god of choice because the concept of Shiva explains his convictions somehow. Shiva is his self-image for the moment. Tomorrow it might be a different god. Maybe Vishnu or Brahma. Or maybe a Sumerian god.

Interestingly the reference to Shiva comes up again. Once Clayton confronts Karen Crowder (Tilda Swinton) with the fact that he has carried out Eden’s plan to expose the company, we get this bit of dialog:

Karen Crowder: You don’t want the money?

Michael Clayton: Keep the money. You’ll need it.

Don Jefferies: Is this fellow bothering you?

Michael Clayton: Am I bothering you?

Don Jefferies: Karen, I’ve got a board waiting in there. What the hell’s going on? Who are you?

Michael Clayton: I’m Shiva, the God of death.

“I am Shiva, the god of death.”

Again it’s Shiva, the god of death, and this time the line is used as a final punctuation to the film’s climax. However, unlike Eden, Clayton uses the line more for its effect on Crowder and Jefferies than from a sense of personal identification. What might that effect be? Within the context of the film, and within the context of a largely non-Hindu society, this line comes as a kind of shock, a non-sequitur of sorts, that specifically draws attention to itself. I imagine the filmmakers intend the line to read something like “I am the fictional, mythological god Shiva (in a metaphorical sense of course) who is bringing about a kind of death to you, a death that you are powerless to avoid.” In other words, we are not to assume that the filmmakers or the characters actually believe in the existence of Shiva, rather the idea of Shiva is appropriated in order to convey something meaningful.

To the person who does not believe in Shiva, such a line might merely have a kind of cool factor. To a devout Hindu this line might be somewhat disconcerting – I don’t know because I am not a Hindu. What is interesting is that none of the characters have made a conversion to any religion, or even gone through any particularly religious experience. Edens has had mental breakdown because of deep moral tensions. Clayton has crossed over into a personally powerful existential decision. But neither have obviously embraced Hinduism. (If I missed something, let me know.)

Interestingly, the narrative arc of Michael Clayton follows a traditional Western style morality tale. And yet, one could say the characters, who do not overtly believe in any god, still wrestle with issues that derive their moral content from a Judeo-Christian heritage, and then, ironically, symbolically claim a Hindu god as justification for their actions. I find this both puzzling and not surprising. It is exemplary of the pluralistic/post-modern society that I live in.

In the film’s final shot we see Clayton riding alone in the back of a taxi. It is a meditative shot. He does not look happy or fulfilled. Maybe he is, but his countenance is rather sullen. Has he saved himself by his actions? Has he found redemption for who he was? How can he be sure he has actually changed as a person? None of these questions are answered. One could say that finally he made the right decision after a life of bad ones, and that is good. But one could say that he still has not solved the deeper question of his existence.

The radical truth is that in a world without a God that stands as an ultimate source of meaning then any decision made by Clayton does not really have any meaning. His final decision, though it may resonate powerfully within us the viewers, doesn’t really matter, no matter how personally, existentially transforming it may be for him. At best one can say he made his decision, so what. Any decision would have had the same value. But, of course, we know deep down that can’t be true. We live knowing there is right and wrong, and what we believe we believe to be true.

Crimes and Misdemeanors

Consider the film Crimes and Misdemeanors, Woody Allen’s brilliant 1989 film about morality, choice, and justice. In this film Allen explores how morality flows from where one begins, that is, from the set of presuppositions one claims about God, the universe, our existence, meaning, etc. He also seriously toys with our expectations (our need) for justice to win out.

The film is also very much about the existence, or non-existence, of God, and what that means. I love this quote from Judah Rosenthal:

I remember my father telling me, “The eyes of God are on us always.” The eyes of God. What a phrase to a young boy. What were God’s eyes like? Unimaginably penetrating, intense eyes, I assumed. And I wonder if it was just a coincidence I made my specialty ophthalmology.

There is something both sinister and humorous about it. It also represents our modern tendency to analyze ourselves and mistrust our motives.

But there is so much more to consider in this quote and in this film. The following two part video analysis is an excellent overview of the film’s themes:

When I first saw Crimes and Misdemeanors I was both stunned and thrilled. At the end I thought “perfect”, that’s how it should end, with him getting away with murder, not because I wanted him to, but because I so expected him to get caught and I liked the irony. Allen turns everything on it head and gets us to think. Thinking is a good thing, especially about truth and morality.

Our view of God has a great deal to do with how we understand and appreciate Crimes and Misdemeanors. If there is no God are the characters and their actions meaningless? Is our desire for justice merely a temporary chemical reaction to a situation that emerged from the chance combination of sub-atomic particles? Or do we live as though our desire comes from someplace more profound?

[Side note: In Star Wars, when the Death Star blows up the planet Alderaan, do we merely observe the rearranging of material particles (something of ultimate inconsequence), or do we assume that blowing up a planet and its inhabitants is an act of evil? Get over it old man Kenobi, you moralist! That was no tremor in the force. Probably just gas.]

Finally

I am inclined to think there is no such thing as a narrative without some moral content.Either a series of events are purely a-moral, an arbitrary grouping of cause and effect acts without meaning, or they are, in some way, the result of decisions. If decisions are involved then those actions have meaning and therefore have a moral dimension. I see narrative as being fundamentally the result of decisionsand therefore fundamentally moral.

But as soon as well make a moral claim we assume an absolute. We might say our claim is purely cultural or situational or merely a personal decision, but we don’t really live that way. When we say war is wrong, or rape is wrong, or Nazi death camps are wrong, we assume a universal. And if we claim universals then what is our foundation? This is the very point at which our belief or non-belief in God, god, or gods, has the most gravity.

Woody Allen leaves the question open in Crimes and Misdemeanors, but he is relying on the fact that we cannot. He creates in us a tension, and something to talk about. Michael Clayton leaves us somewhat satisfied, yet under its surface there is no final meaning, its only opinion. What is great about both of these films is how they tap into the very human predicament of having to sort out the deep questions of how we are to live our lives and upon what are we going to base our choices.

I can be in awe of an artist even though our beliefs about God may differ. What we have is a common humanity, which is a truly profound connection. Even so, it is worth calling out our differences as well, not for the sake of creating divisions, but of understanding each other and seeking the truth. For we are, by nature, truth seekers. But then that’s another universal I am claiming.