>Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris directed Little Miss Sunshine. Recently they were interview on NPR Radio here. They were asked to list some of their fave DVDs. Here they are (shamelessly copied directly from the NPR web site):

This Film is Not Yet Rated (2006): A Sundance favorite, this film shines light on the secretive Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) rating system. Dayton describes it as a dramatic and funny detective story that is both entertaining and troubling.

Visions of Light (1992): A film for film lovers, this documentary about the art of cinematography features clips from more than 100 movies. The film helps viewers appreciate cinematography. “It makes anyone who loves film a better viewer,” Dayton says.

Coming Home (1978): Hal Ashby’s 1978 film stars Jane Fonda as a nurse in a veterans’ hospital and Jon Voight as a wounded Vietnam vet. Dayton and Faris are both fans of Hal Ashby and consider this to be one of his best works. This film about the after-effects of war resonates as truthfully today as it did 25 years ago, Dayton says.

Gates of Heaven (1980): This comical documentary about the pet cemetery business helped launch Errol Morris’ career as a director. “It’s a film that keeps unfolding and becoming richer and funnier and sadder,” Dayton says. Faris adds that this rich character study is her favorite film. “Everyone should see this movie,” she says.

A Touch of Greatness (2005): This Independent Lens documentary profiles Albert Cullum, a maverick public school teacher who encouraged creativity in the classroom. Faris appreciated the beautiful archival footage shot by Robert Downy Sr. and describes the film as an incredible portrait of an amazing teacher. “If we had more teachers in the country like him,” she says, “we’d have a great country.”

Half Nelson (2006): Academy-Award nominee Ryan Gosling plays an idealistic public school teacher who develops a friendship with a student after she finds that he has a drug problem. Faris and Dayton praise Gosling and Shareeka Epps for incredible performances in a film that did not shy away from moral ambiguity.

The Five Obstructions (2004): This 2004 documentary about the creative process profiles a filmmaker charged with the task of remaking his favorite film five times — each time with a different obstacle. Dayton recommends this film for anyone involved in the creative process. Faris describes it as “creative hazing” and appreciates its illustration of the struggle and the joy of the artistic process.

ALSO RECOMMENDED

The Science of Sleep (2006)

The Office, U.S. Version, First Two Seasons

Mr. Show, The Complete Fourth Season

Unfortunately, I have to admit that the only film on this list that I’ve seen is Visions of Light, which I, in fact, mentioned in my previous post.

Category: movies

Cinema Sublime: considering contemplative cinema’s relationship to the infinite

Okay, the contemplative cinema blogathon is voodoo. I mean, I have been thinking about it too much when I should be working on my thesis. Bad, bad, bad. So here are more of my thoughts:

Contemplative cinema seems to have certain aesthetic traits. An excellent overview of the most obvious traits can be found at The Listening Ear: Defining Contemplative Cinema (Bela Tarr). I have also tried to triangulate somewhat on the traits with these posts on “Art Cinema” Narration: Part One, Part Two, and Part Three. Then I tried, somewhat unsuccessfully, to describe the distancing aspect of contemplative cinema by way of contrast here. And finally, I tried, feebly, to find some links to 20th century painting and contemplative cinema here. In some ways I feel my posts have only been scratchings at the surface and not really getting at the heart of the matter. I anticipate this post will also add to the scratching. Probably because I do not see a “solution” to the question of contemplative cinema, merely a myriad of signifiers in an ever expanding galaxy of meaning.

I firmly believe that contemplative cinema is not the sum of a set of unique traits – the long shot, narrative in the background, etc. – although there certainly are unique traits. Contemplative cinema must, I believe, come from a set of ideas – loosely organized and very arguable for sure. What those ideas are is too big of a topic for this post, but I have an idea that the ideas behind and underneath contemplative cinema are complex, very human, and have deep roots planted long before cinema was born.

Here’s just one possible approach to one kind of contemplative cinema.

The concept of the sublime and contemplative cinema

In the 17th and 18th centuries our (richer) predecessors trudged through Europe on their grand tours seeking that fullness of experience that would round out their lives and, if young, complete their educations. When confronted with the awesome grandeur of the Swiss Alps, these trekkers gaped in fearful admiration at nature’s terrifying and beautiful power. Trying to give name to the strange and conflicting experience of fearfulness and mutual attraction, philosophers gave it the name “sublime,” and then set out to argue about it from then until now. Edmund Burke and Emmanuel Kant both dove masterfully into the subject, but it is Schopenhauer who may have clarified it best for us when he listed off the stages of going from mere beauty to the fullest feeling of the sublime (taken from Wikipedia):

Feeling of Beauty – Light is reflected off a flower. (Pleasure from a mere perception of an object that cannot hurt observer).

Weakest Feeling of Sublime – Light reflected off stones. (Pleasure from beholding objects that pose no threat, yet themselves are devoid of life).

Weaker Feeling of Sublime – Endless desert with no movement. (Pleasure from seeing objects that could not sustain the life of the observer).

Sublime – Turbulent Nature. (Pleasure from perceiving objects that threaten to hurt or destroy observer).

Full Feeling of Sublime – Overpowering turbulent Nature. (Pleasure from beholding very violent, destructive objects).

Fullest Feeling of Sublime – Immensity of Universe’s extent or duration. (Pleasure from knowledge of observer’s nothingness and oneness with Nature).

For examples in painting we might look at Caspar David Friedrich’s Cloister Cemetery in the Snow (1817-1819)…

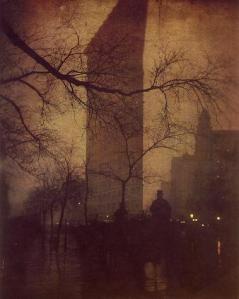

In photography we might consider Edward Steichen’s The Flatiron (1905)…

Prior to the 20th century the sublime was found mostly in nature, which, for all its potential danger, is fundamentally morally neutral. But in the 20th century unimagined horrors were foisted on humankind – trench warfare in WWI, the Nazi genocide of European Jews, the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, and the list continues. I would argue that a shift occurred in the concept of the sublime to include the fact that human beings commit such horrors, both consciously and subconsciously, and that that inclusion has had a significant affect on the arts including cinema. In other words, one could extend concepts of turbulent nature, overpowering turbulent nature, and the immensity of the universe’s extent to the apparently overpowering aspects of human desire, the power of technology, and human evil. A fully engaged response to this reality could include a scientific approach where one just has to face up to the emptiness of human existence in a world created by time + matter + chance, or it could explore the soul as though on a sea of meaning both frightening and hopeful.

What I am saying is nothing new. However, I think the modern concept of the sublime, with its roots going back to 17th century, may offer pointers towards an understanding of contemplative cinema. For example, it is obvious the Bergman’s The Silence or Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour are artistic explorations of a human response to the modern world from within a position of the nihilistic universe, but a more sublime film, such as Tarkovsky’s Stalker, might address the same concerns, but from a different vantage point. I would argue that that vantage point is not the scientific perspective of the individual in a cold universe, but the soul in relation to the infinite. This is not to say the Bergman or Resnais (in these examples) did not make contemplative films, but they do so by rooting the viewer in the narrative process and therefore in a materialistic world. I propose a sublime contemplative film calls the viewer beyond the narrative – and to me this seems to be a higher level of contemplation.

Another angle on the sublime might be:

The experience of the sublime involves a self-forgetfulness where personal fear is replaced by a sense of well-being and security when confronted with an object exhibiting superior might, and is similar to the experience of the tragic. The “tragic consciousness” is the capacity to gain an exalted state of consciousness from the realization of the unavoidable suffering destined for all men and that there are oppositions in life that can never be resolved, most notably that of the “forgiving generosity of deity” subsumed to “inexorable fate”. (also taken from

In this sense the sublime is an almost religious concept – one might think of the concept of fearing God (a combination of love, reverence, and trembling), for example. A contemplative film which has its roots in the sublime might then call on the viewer to transcend narrative construction (mentally speaking) in order to enter into a feeling of the “tragic consciousness” of the universe, and thus transcend narrative climax. The potential issue with this way of thinking, however, is the reality that the viewer’s response is personal, which is unique for each viewer. That is why I cannot go so far as to say the characteristics of contemplative cinema are a set of particular visual or narrative cues. But there may be characteristic goals.

Does it make sense to see contemplative film, then, as primarily non-narrative? One might consider Love Song (2001) by Stan Brakhage, an abstract, undulating, “hand-painted visualization of sex in the mind’s eye.” No doubt this short, purely abstract film seeks to produce an effect within the viewer. No doubt it calls of the viewer to be open to exploration of the self in some capacity. But what can we really say about it? In my opinion, sublime contemplative film still needs something more tangible to hang on to, and part of that tangibility is narrative, even while seeking to transcend narrative.

Love Song (2001)

Love Song (2001)

Of course, a question raised by considering a film such as Love Song is whether or not sublime contemplative cinema succeeds by accurately representing something that is already sublime, or whether by using cinematic means, however so, to induce a feeling of the sublime in the viewer.

A better option may be to consider another Stan Brakhage film, Window Water Baby Moving (1962). In this powerful short film about the birthing process there is the natural narrative of the birth. Although told unconventionally, there is enough of a narrative, and just enough balance between abstraction and reality, that one can “enter” into the film more fully. This entering process then allows the transcending process to be more substantial, that is, it seems more likely that the viewer will end up in a different place at the end than at the start, psychologically and spiritually speaking. The sublime nature of the piece shines through in the combination of the beauty of body, life, and love with the graphic intensity of actual birth in bloody closeup.

Window Water Baby Moving (1962)

Window Water Baby Moving (1962)

Interesting, Window Water Baby Moving is constructed via the often rapid juxtaposition of many different images, and thus potentially subverts the idea that contemplative film is necessarily and characteristically made of lengthy shots in which very little action takes place.

Finally, a cinema of the sublime is not a genre or style or even a set of aesthetic choices so much as it is a particular attitude to the place of human beings in the universe. How this plays out in the arts can be varied and fascinating. I believe the concept of contemplative film includes the concept of the sublime whether is is of primary emphasis or resides in the background. I’m sure much more can be said, but I will leave it there.

les carabiniers and the death dance of imperialism

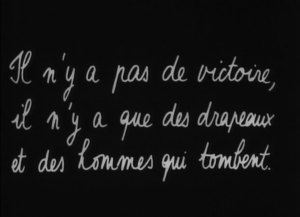

Finally, the scene ends with this quote:

il n’y a pas de victoire

il n’y a que de drapeaux

et des hommes qui tombe

In the context of the film this scene shows the extent to which the carabiniers have been brainwashed by their government – the king himself has asked them to do what they do, or so they believe. The scene also extends outward to the whole reality of war, of cinematic depictions of war, and to our present day. For me there is a mental connection with the final scene in Full Metal Jacketwhen the American soldiers come face to face with the young female Vietnamese sniper. As she lies on the floor of the shattered building, mortally wounded and writhing in pain, the soldiers stand around discussing her fate.

A portion of that scene goes like this:

DONLON stares at her.

DONLON

What’s she saying?

JOKER

(after a pause)

She’s praying.

T.H.E. ROCK

No more boom-boom for this baby-san. There’s

nothing we can do for her. She’s dead meat.

ANIMAL MOTHER stares down at the SNIPER.

ANIMAL MOTHER

Okay. Let’s get the f**k outta here.

JOKER

What about her?

ANIMAL MOTHER

F**k her. Let her rot.

The SNIPER prays in Vietnamese.

JOKER

We can’t just leave her here.

ANIMAL MOTHER

Hey, asshole … Cowboy’s wasted. You’re fresh out

of friends. I’m running this squad now and

JOKER stares at ANIMAL MOTHER.

JOKER

I’m not trying to run this squad. I’m just

saying we can’t leave her like this.

ANIMAL MOTHER looks down at the SNIPER.

SNIPER

(whimpering)

Sh . . . sh-shoot . . . me. Shoot . . . me.

ANIMAL MOTHER looks at JOKER.

ANIMAL MOTHER

If you want to waste her, go on, waste her.

JOKER looks at the SNIPER.

The four men look at JOKER.

SNIPER

(gasping)

Shoot . . . me . . . shoot . . . me.

JOKER slowly lifts his pistol and looks into her eyes.

SNIPER

Shoot . . . me.

JOKER jerks the trigger.

BANG!

The four men are silent.

JOKER stares down at the dead girl.

>a beautiful inscrutability

I just saw Le Cercle Rouge (1970) for the first time and I was blown away. I have yet to see Army of Shadows (1969/2006), which I desperately want to see very soon. I had seen Le Samouraï (1967) a few years ago, but I was not as taken with that film as with Le Cercle Rouge, although it is also very good.

I’m no expert on Melville, but in my mind Le Cercle Rouge is an example of brilliant and controlled filmmaking. As I watched this police procedural proceed with much less flashy action and dialogue typically found in American films of the same ilk, I couldn’t help but wonder at its director and how he thinks. I don’t mean what he thinks (or thought, actually) about, but “how.” What really was going on in his head? [Note: I tend to think of dead filmmakers in the present tense because their films are still in the present tense.]

I wonder because I fancy myself to be a filmmaker (in the future tense, but still…) and I am fascinated with Melville’s obvious assurance of his narrative capabilities. I say this because the crux of the film, the extended jewelry heist scene, takes many minutes of screen time with only one word of dialogue being uttered. In fact, there is very little on the soundtrack at all during this scene. One could say that Melville made a silent film and put it right in the middle of this big budget (relatively speaking) star vehicle movie at possibly the most vital narrative moment. And my eyes never left the screen. How did he do that?

I could analyze the scene shot by shot, but that might be like the old saying about analyzing a joke – you kill it in the process. In other words, for a “how did he make it work?” perspective I can only wonder in awe. In fact, that gets me thinking… for all the studying of filmmaking I’ve done over the years, and all the film/video production I’ve done in years past, and the television production classes I’ve taught (how many years ago??), I still don’t think I can really describe anything beyond basic filmmaking tactics and strategies. There is, and I believe always will be, a certain amount (great amount is more like it) of mystery to the process – as it is with all the arts. That is why those interesting little vignettes showing the filmmaker on the set discussing lighting and acting strategies reveal almost nothing of the true creative process – which is largely invisible. One can only see the outside shell of the process. As far as I’m concerned, there’s something really beautiful about all that.

At least we still have the films to watch – which is really what it’s all about anyway. For now, I have to see Le Cercle Rouge again, watch Le Samouraï again, and see Army of Shadows.

La Noire de…

This morning I watched La Noire de… (Black Girl). Directed in either 1965 (according to the DVD box) or 1966 (according to IMDB) by Ousmane Sembene (the “father” of African cinema), La Noire de… was his first film. And this was the first time I had seen it in 20 years.

The plot is rather straightforward (warning, I will be discussing the ending of the film, etc.):

A Senegalese woman [Diouana] is eager to find a better life abroad. She takes a job as a governess for a French family, but finds her duties reduced to those of a maid after the family moves from Dakar to the south of France. In her new country, the woman is constantly made aware of her race and mistreated by her employers. Her hope for better times turns to disillusionment and she falls into isolation and despair. The harsh treatment leads her to consider suicide the only way out. (taken from IMDB)

The story is told by jumping around between Diouana’s (Mbissine Thérèse Diop) plight in Antibes, France and flashbacks to her life in Dakar, Senegal before she went to France. This jumping around creates a deeper sense of the psychological complexity underlying the relatively uncomplicated surface.

Frankly, I don’t know very much about African cinema, or African culture(s) for that matter, but I find this story to be both simple and powerful, in particular because of the use of a traditional African mask as a symbol throughout the film. Here’s how I would suggest “reading” the mask within the narrative:

In the plot Diouana was hired by a white French couple to take care of their children. In her enthusiasm she gives them a traditional African mask. The couple take it and remark that it looks like the genuine article (truly African).

They don’t know exactly where to hang it up. The husband (Robert Fontaine) looks at the other masks they have – presumably just tourist items, not the genuine article.

Finally he sets it down on a shelf and they stare at it.

Then we see a close up of the mask.

Then, interestingly, we cut to a close-up of Diouana’s face framed in roughly the same manner as the close-up of the mask. This edit creates a visual relationship between Diouana and the mask. However, what it means is not exactly clear. Has she given up her mask – metaphorically – and what would that mean? Is she now more vulnerable as a person, in terms of who she is? Or is this a good thing that she has given up her mask?

This image of Diouanais one of the only times we see her with a smile; her face looks relaxed and she seems to have no worries.

The story takes a nasty turn as she slowly realizes that she was lied to by the French couple, and it is fair to say that she had false hopes based on her romanticizing of France and its culture. It is also fair to say that the French couple, who now treat her badly, are also merely acting out of their position as colonizers and that they, also, have in turn romanticized Africa.

At this point the husband takes her suitcase and the mask back to Dakar to give it to Diouana’s mother (I could not find her screen credit). He also tries to give her Diouana’s pay that is due. Diouana’s mother refuses to accept the money. The Frenchman walks away followed by the young boy (Ibrahima Boy) who holds the mask over his face. The Frenchman walks quickly as though he is trying to get away from the boy.

After the Frenchman boards the ship to leave Dakar the boy stares at him through the mask…

…and then slowly lowers it to reveal his own (true) face.

I would say that Diouana gave up her mask and paid the price. Her French “owners” never did understand. The final image seems to be saying symbolically that the maskof Africa (or specifically of Senegal) has driven out the colonizers (specifically the French). In this sense, one might also say that the French came and went, but the true Africa still lives on.

>The Mayflower and the Life of Cinema

>If I remember correctly the summer of 1977 was rather hot. This was also the year that Star Wars was released in theaters. I mention this because the only theater in the thriving metropolis of Eugene, Oregon that had Star Wars was the (now gone forever) Mayflower, and the Mayflower did not have air conditioning. Good riddance I say.

The Mayflower was right across the street from the run-down frat house used in Animal House the next year – also gone. Why it was called the Mayflower I do not know, but rumor had it that it was slated for demolition, but the revenue generated from Star Wars kept it standing for another couple of years. Good riddance, yes, but not without some sense of loss. I mean those were the days. The next year – 1978 – I would sneak into the same theater with a friend and watch Hooper three times back to back – hiding under the seats between shows – and dreaming of becoming a stuntman. Yes, good times for a kid.

In 1977 I was eleven going on twelve and that was the year in which another movie patron told me to shut up – actually told me and my friend to shut up (yes, the same friend I saw Hooper with). I was so mortified that no one has ever told me to shut up in a theater again, as far as I can recollect. But I cannot take all the blame. Some of the blame goes to Star Wars. You see, Once I had seen Star Wars that first time, I had to see it again. In fact, I saw Star Wars six times the first week of its release – and twelve times that year (all at the Mayflower). By the fifth or sixth viewing my friend and I had most of the dialogue memorized. From the first moments of the 20th Century Fox logo I would feel giddy with anticipation, and at some point during one of those viewings my friend and I just couldn’t keep ourselves from quoting out loud each line. Needless to say some of the other filmgoers were not amused.

Why do I say this? Sometimes I get annoyed going to the movies; People talking, cell phones ringing, not being able to pause the movie if nature calls, having to see the film at a particular time decided by someone else, bad reel changes, bad odors, poor wine selection, etc. You know what I mean. However, I have to say that, for the most part, the multi-plex for all its crass commercialism is an improvement over the single screen theaters of the past – at least for those films that would have already been coming to town, since multi-plexes still don’t show many truly independent or foreign films. The seats are better, the projectors are better (the projectionists are not, however), the sound is better, etc. You know what I mean. So the reason I bring this up is that it has become a common move to periodically decry the death of cinema, even from it’s birth. Louis Lumière once said, “The cinema is an invention without a future.” It would be easy for me to long for those golden days of my youth when I could watch films in rickety theaters with bad pictures, bad sound, bad odors, and annoying patrons (including myself I guess). But that would be like longing for the good old silent film days, or the good old days when the screens were smaller, or the good old smoke filled theater days, or the good old pre-steadycam days, whatever. One might as well long for the good old pre-film days when the cinema was just a wonderful dream, just a twinkle in the eye really – think of all the possibilities.

In a recent piece for the New Yorker (Big Pictures), David Denby writes about how cinema as we know it, or have known it, is changing, and probably not for the better. I can’t say that I disagree with much that he writes, and I won’t pretend to have a tenth of his knowledge, but I don’t have the same fear that he expresses. He describes the (mostly past) utopian vision of seeing a film at the local neighborhood theater:

[W]e long to be overwhelmed by that flush of emotion when image, language, movement, and music merge. We have just entered from the impersonal streets, and suddenly we are alone but not alone, the sighing and shifting all around hitting us like the pressures of the weather in an open field. The movie theatre is a public space that encourages private pleasures: as we watch, everything we are—our senses, our past, our unconscious—reaches out to the screen. The experience is the opposite of escape; it is more like absolute engagement.

Denby then contrasts that cinematic utopia with this description of seeing a film in a modern multi-plex:

The concession stands were wrathfully noted, with their “small” Cokes in which you could drown a rabbit, their candy bars the size of cow patties; add to that the pre-movie purgatory padded out to thirty minutes with ads, coming attractions, public-service announcements, theatre-chain logos, enticements for kitty-kat clubs and Ukrainian bakeries—anything to delay the movie and send you back to the concession stand, where the theatres make forty per cent of their profits. If you go to a thriller, you may sit through coming attractions for five or six action movies, with bodies bursting out of windows and flaming cars flipping through the air—a long stretch of convulsive imagery from what seems like a single terrible movie that you’ve seen before. At poorly run multiplexes, projector bulbs go dim, the prints develop scratches or turn yellow, the soles of your shoes stick to the floor, people jabber on cell phones, and rumbles and blasts bleed through the walls.

My thought is this: Denby’s utopia does sometimes exist, especially at the few remaining art-house theaters and at some college campus or film festival screenings. I also think it exists when a group of friends gather around the flat panel HDTV at someone’s home, after a great meal and good wine, crank up the surround sound, pause the film half way for potty breaks and glasses of good scotch, and then follow the film with a discussion. In fact, Denby’s dour description of the multi-plex experience is really no different than the theater experiences we had in the “good old days.” Communal cinematic experiences are always fraught with potential problems as well as potential joys. Today, however, we have more viewing options available to us. Certainly I decry Denby’s imaginary experience of watching Lawrence of Arabia on a video iPod just as much as he does, but that’s just it, it’s an imaginary experience. The films being watched on video iPods today are Pirates of the Caribbean (another Denby example) and frankly I couldn’t care less if someone watches it on a two inch screen. I am inclined to believe that films will find their most appropriate presentation options and people will seek out those options with some films gaining a large audience through video iPods and other films through other means.

So finally, I wouldn’t give up the summer of 1977 and my twelve times watching Star Wars at the lousy Mayflower. I also wouldn’t give up the 16mm screenings of the cinematic cannon in those cold lecture halls I frequented in college. If I have the time to get to the multi-plex or the local art-house theater I will. And if could afford to buy a video iPod I would. Cinema is not dead. The movies keep moving. In fact, I’m inclined to think that motion pictures are as alive today as ever before. What I do see changing is the almost hegemonic power of Hollywood and the limited methods of delivering movies to all of us. Old cinema gets old (and sometime better with age), just like we all do, and new cinema is born. This is not a value judgment. It’s just life. And we all know how life is.

more fun with contemplative cinema

New York, N.Y.

Franz Kline, 1957

Takka Takka

Roy Lichtenstein, 1962

A thought experiment on “contemplative cinema.”

As I mentioned in my previous post (towards an exploration of contemplative cinema) on the subject, I see contemplative cinema producing a distancing effect, but not in terms of the politics of the image, as one finds with Godard. In other words, not in terms of power. I see the distancing effect being much more subtle and ultimately inviting – a kind of drawing one into the subtext of the film by way of “asking” the viewer to contemplate the object (film, image, etc.). Contemplative film is, in this way, highly connotative. The reason I bring up Godard by way of comparison is because his work is such a good example of one kind of of disanciation, and I want to foreground the other. One side of distanciation pushes the viewer back, making her aware of the contingent and contrived nature of cinema, of the power of the cinematic image, and the ability (even necessity) of subverting that image by the viewer. The other side is to see the process helping the viewer to more fully and consciously participate in the philosophical and artistic implications of the cinematic image. For the contemplative film I believe those implications are frequently grounded in the sublime rather than the political.

[Note: I use the term “political” in a structuralist/post-structuralist sense developed within screen theory which treats filmic images as signifiers encoding meanings but also, thanks to the apparatus through which the images are projected, as mirrors in which, by (mis)recognizing themselves, viewers accede to subjectivity. In my view, contemplative cinema is concern with other things.]

In this light, I wonder what connections to other arts can we make. I believe that comparisons can be a good way to zero in on the topic. One thought is in the comparison we can create by placing two painting genres side by side: abstract expressionism and pop art. I see these two painting genres to be somewhat similar to the differences we find between contemplative cinema and what we might call, more or less, political cinema. It seems to me that New York, N.Y. by Franze Kline (1957) can be compared with Takka Takka by Roy Lichtenstein (1962) along similar lines as one might compare, for example, The Mirror by Tarkovsky (1975) and Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle by Godard (1967). I don’t have the time at this point to go into a full analysis (I would love to if I could), but I think there are a few salient points. I think it is fair to say that both paintings call attention to themselves, that both point to something beyond the obvious features of each, and that Takka Takka sets one back on one’s heels bit while New York, N.Y. calls for attentive, yet quiet contemplation. That is the difference, as I see it, between two possible intentions of distanciation.

This kind of comparison seems valid to me, but I am curious as to how others see it. I am also curious as to other contemplative cinema comparisons with non-cinema stuff, such as landscape archtecture or poetry. I welcome your comments.

>humor to ponder

towards an exploration of contemplative cinema

Here are some of my thoughts on the concept and/or reality of contemplative cinema. I am writing this in response to the contemplative cinema blogathon . I must include that I don’t know if I will produce any clarity around the subject. I merely hope to explore some possibilities for approaching the topic.

The folks at the blogathon are loosely defining contemplative cinema thus:

contemplative cinema: the kind that rejects conventional narration to develop almost essentially through minimalistic visual language and atmosphere, without the help of music, dialogue, melodrama, action-montage, and star system.

Or, one could say “boring art films,” as so many do.

And so I dive (or flop) in…

What is going on in a film in which nothing is going on? As I ponder this question I cannot help but ponder a seemingly unrelated question, but one which is actually fundamental: Where is the film?

The contemplative film is, as it is with any film, both up there on the screen and in here – inside my head, and inside yours. That is why we can have very different subjective experiences of a very real aesthetic object – even disagreeing about seemingly basic aspects of the object itself. So, while we are conversing about those specific contemplative films out there in the world in which we can all share, we are also talking about the contemplative films which we construct in our heads. [Note: I won’t pretend to be either a seasoned film critic or professional philosopher, but I will try to make myself clear as best I can.]

In other words, a film is a complex combination of a number of things: images, sounds, editing, beginnings and endings, scenes, characters, music, etc. These complex combinations are organized in such a way that the viewer is encouraged to create a mental construction that is, in a sense, a mental version of the film, or what we might call the “true” film. This so called “true film” or mental film is the goal of the creator (or creators) of the film that is up on the screen. And films are made knowing that you the viewer have the capacity to “put it all together.” [It should be obvious on this point that I am siding with the Russian constructivist theorists via David Bordwell’s great book Narration in the Fiction Film (1985).]

An obvious question, then, is what are the cues being given us by contemplative films that other films do not provide, or provide differently? I believe the answer to this question could be long and debatable, even more so than a list of typical genre characteristics. However, I will posit that what makes a contemplative film one as such, is that the process of cueing the viewer is for producing two effects: (1) break the tendency to forget the brain is constructing the film – an act of distanciation, and (2) with a view to effect number one, to encourage the viewer to go beyond narrative construction into a higher plane of self-awareness. The first is about inviting the viewer to move beyond expectations of mere narrative construction, and the second is about inviting the viewer to become a conscious and personal participant in the film experience.

That’s all fine and good, but one could say the same thing about some of the not-so-boring art films, say Weekend by Godard (at least I don’t find the film boring or slow). Having the film push one away from itself, so to speak, for the purpose of thinking about something other than an imaginary story one can escape into, is a fundamental characteristic of modern art as a whole – to make strange, the “shock of the new,” etc. What then makes contemplative cinema unique? Or, maybe a better question is: What is it that we are contemplating? The film, ourselves, a cosmic spiritual dimension, the nature of film itself? In this sense I believe that intent comes into play, but I do no propose that we try to read any director’s mind. No, I believe that the intent of a film will emerge from its own qualities to suggest and imply a certain approach. Contemplative cinema, it seems to me, calls us to a mental state that is not always easy to clearly defined, yet we know it when we experience it, like love or ennui.

So then, what is going on in a film in which nothing is going on? A great deal. First, the mind is fully capable of being as active as it is with any other film regardless of pace or general “boringness.” However, with a contemplative film one might ask if a greater burden (or a more substantial request) is being placed on the constructive activities of the mind. This may be so. Certainly it appears that less is present on the screen so the brain may have to work harder (that is debatable). Second, one might ask if a contemplative film relies on more than just the mind to do the constructive task. This is the key question, I believe. In other words, might the intent of a contemplative film be to activate the soul as well as the mind?

So then, where is the film? It is up there on the screen, in my head, and, if I let it, in my soul. [Note: I am using “soul” rather loosely. I do not intend to dive deeper into a discussion of metaphysics per se.] Contemplative cinema is a cinema of the soul. That is its intent.

Of course, watching some contemplative films may feel a little like staring at one’s navel. And yet, a powerful film in this vein may, in fact, produce a powerful and profound spiritual experience for the viewer. [I am using “spiritual” rather loosely as well.] One might say that a “successful” contemplative film moves along a path from objective film to subjective film to spiritual film. But I want to be careful with the term “spiritual.” I do not mean to imply that such films transport one to a different plane, or that one, via the film, will somehow transcend this existence. No, contemplative film is not about an “out there” or “up there” or even cosmic gesture. I see the soul as being deeply rooted in this existence, in this world. In fact, one could say the intent of contemplative film is to strip away much of the artificiality found in mainstream cinema in order to encourage the viewer to more fully engage with reality.

Finally, if what I have laid out (and I admit not very well) is true, then what one brings to the film at hand is paramount – and I’m not talking about the popcorn. On the other hand, I don’t believe there is a formula or list for what one should bring. But it seems to me that a person who is inclined to explore deeper existential questions, who is inclined to see life as a journey, and who finds the quieter moments in life to be valued, may have brought the right things.

By way of example, a comparison might be in order – in this case Godard and Tarkovsky. I have already mentioned Weekend as a film which has some qualities found in contemplative cinema, yet does not, in my opinion, qualify as a contemplative film. In Weekend there is a famous tracking shot that follows a car driven by the two main characters as they try to pass a long line of cars on a country road.

The camera follows the progress of the car as it passes the other cars in the traffic jam…

…and continues past a number of social vignettes…

…until we see the reason for the traffic jam, a bloody, gruesome accident…

…which our characters speed by without a care.

…which our characters speed by without a care.

This shot takes up around 9 minutes (if I am not mistaken) and feels longer. Clearly the viewer is asked to consciously participate in the film in a way different from a more typical, seamless narrative structure. Godard does not seem to care if one becomes more attuned to one’s soul, he is concerned about the viewer being more aware of the film in the world (and the viewer in the world). This has a more critical arch to it and less of a contemplative arch as I am describing above

This shot takes up around 9 minutes (if I am not mistaken) and feels longer. Clearly the viewer is asked to consciously participate in the film in a way different from a more typical, seamless narrative structure. Godard does not seem to care if one becomes more attuned to one’s soul, he is concerned about the viewer being more aware of the film in the world (and the viewer in the world). This has a more critical arch to it and less of a contemplative arch as I am describing above

…and so I humbly submit

>Movies and Mastication

>I could have titled this Film and Food, but Movies and Mastication just has a certain ring to it.

Okay, so I have this reoccurring tendency to compare watching movies with eating food, and the preparation of a meal with the making of a film. I know the link between the two is technically weak. I know I am not the first person to think of it either. And I also know that in many cases the analogy can offer some interesting insights. A simple example is that one’s taste in both categories can greatly improve with some guidance and education. Another example is that a diet of either only junk food or junk films will lead to a kind of jelly-fied bloating.

Lately, however, I’ve been thinking of the combination of food and film. That is, the selection of particular comestible spreads with particular cinematic fare for an overall enhanced experience. I figure this is a little like choosing an ideal double feature combo. For example, one might say that pizza and film “X” make a great combo (although I am imagining gourmet food as well). Imagine you have invited some friends over to watch one of your all-time favorite films and you also have to provide dinner (or lunch); what would be the film and what would be the meal?

Truth is, I love to cook, and I’ve been thinking for a long time about working on a cookbook. Today I had the idea of writing a cookbook that combined my passion for cooking and my passion for good films into a food/film combination book. And although I know the concept just might work, I am stumped for ideas. Plus, I want to start inviting more friends over for films and food on a more regular basis. So I’m looking for any ideas anyone has. Let me know what you think.

I think it would be appropriate to include a list of drinks as well – good wines, mixed drinks, iced tea, whatever.

Also, has a book like this been done before? I’m curious.