Man is the servant of nature, and the institutions of society are grafts, not spontaneous growths of nature. ~Napoleon

The quote above is taken from the introduction of Honore de Balzac’s The physiology of marriage; or the MUSINGS of an eclectic philosopher on the happiness and unhappiness of married life. Balzac, who was the great recorder of the emerging bourgeois class of French (and European) society, and who cast his powerful gaze upon the vagaries of the human soul, plays a part, albeit through his literature, in Jean Renoir’s Boudu sauvé des eaux (1932). The idea that society has rules, and that humans are always trying to break them while judging others by those same rules, is central to understanding Boudu – both the film and the character.

In the story of Boudu, the bookshop owner M. Lestingois (Charles Granval), an example of this new bourgeois male, gets upset when he discovers that Boudu has spat in his copy of The physiology of marriage. “The man who spits in Balzac’s ‘Physiology of Marriage’ is less than nothing to me,” he says. Both comically and symbolically this moment is a nice touch. Renoir is drawing comparisons and contrasts through the film, and especially is poking fun at this new French middle class and all its trappings.

In this sense, though Boudu is the clown, the true comedy is with everyone else.

But Renoir, who, like Luis Buñuel frequently satirized the bourgeois, is ultimately much grander in his scope than mere satirization. I would certainly characterize Renoir’s project as parading before his audience the comical foibles of human beings, and therefore the list of Renoir’s films can, for the most part, be classified as la comédie humaine. But this is not a new insight on my part. What makes Renoir so great (and likely my favorite director), is that he shows humans in all their selfishness, pettiness, and ugliness (he is not afraid to do so), and yet he gets away with it because he has forgiven his characters before the story ever begins. We are watching characters who show us what we are, and yet they have been forgiven by the filmmaker, by their creator, and therefore we can find forgiveness too (for the characters and, by implication, for ourselves). Therefore, we love these characters. With Renoir there is no black and white, and not even grey, there is only the vibrant color of existence and human interaction – something that gets fuller treatment when Renoir begins later shooting his films in color.

For me, having just seen Boudu twice this past weekend was a revelation. It had been around 23 years since I last saw the film. The Criterion Collection DVD is a wonderfully produced copy of the film. But it is not the quality of the DVD that got to me. And it was not merely the incredible performance by Michel Simon as Boudu, as well as the rest of the cast. No, what got to me was the boldness of Renoir – both in terms of the story’s subject matter and of his directorial choices.

We all know Boudu, so I won’t go into plot synopsis, or produce a review. Thematically, Boudu is decades ahead of classical Hollywood cinema, not merely in terms of the sexual content of the film, but also in terms of class consciousness. I’m sure this is not entirely true, and Boudu is probably also ahead of much of French cinema of the era as well, and yet, while U.S. cinema dealt with class distinctions by thumbing it nose at them (think Fred Astaire – working class hoofer in his tuxedo wise cracking his way through high society, showing us the democratic worldview in action), in Boudu we have carefully drawn out and accepted social lines based in class, possibly democratically organized, but certainly socially stratified. And yet, Renoir is such a lover of people, of humanity, that his class distinctions ultimately get played out as comedy and we see his characters as real people filling the role of their class.

Another great element of Boudu is the use of exteriors and natural sounds. Lest we forget, 1932 was very early in the development of sound-recording technology for cinema. [And really the film is copyrighted in 1931.] Shooting talkies was not easy, and shooting exteriors with natural sounds and large group shots was often very difficult. Scenes tended to be shot in studios, and cameras were rendered almost immobile by placing them in sound booths. Typically, multiple cameras had to be used in order to shoot a scene with cutaways and reverse angles because the audio had to be recorded on one track at the time of the shooting – no sound editing later if one had characters talking. Music typically was included at the time of shooting as well. This has all been well documented by many historians. Renoir is using the latest knowledge of sound recording and finding ways to make it work for him.

In Boudu we have both interiors and exteriors. I find the easy transitions between internal and external to work extremely well, including the difficult process of recording and matching the audio. The exteriors seem to almost prefigure the kind of exteriors one will find with the Nouvelle Vague directors of the later 50s and early 60s. In fact, having just seen a couple of early Rohmer films, Renoir does a better job of capturing and mixing exterior audio for effect than does Rohmer 30 years later. In particular, I’m comparing Boudu with La Carrière de Suzanne (1963) because I just saw it as well (ah, thank you DVD player!). Of course Rohmer was doing something different than Renoir.

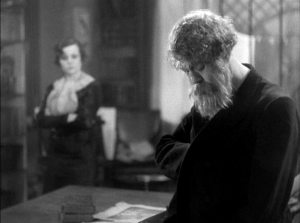

Now here is an exterior/interior transition moment that uses great natural audio and also shows Renoir staging his action along the z-axis. Boudu has just been rescued from the river (in a wonderful exterior rescue sequence with great crowd shots and use of extras) and he is being carried to the Lestingois book shop.

As the crowd moves forward, Mme. Lestingois and the maid rush ahead to open the shop door. The camera has now jumped from exterior to interior, looking through the shop doors.

Up to this point the shot from this angle has been in one take with the action coming towards the camera. Now the camera cuts 180° and we see the action moving directly away from the camera.

They set Boudu down on a bench and then we get several exterior shots of the curious crowd outside.

And then we cut back to an interior shot, this time a medium shot, and slightly different angle than before.

What I like about this little sequence is the ease with which Renoir uses a combination of exteriors and interiors, cuts naturally between the two, and stages his action along the z-axis, thus giving the scene a dynamism that is both inherent and fitting to the story. Renoir is also a master at working with crowds. His ensemble staging and use of the natural energy that crowds provide allows him to more deeply examine human nature because of the interplay among his characters.

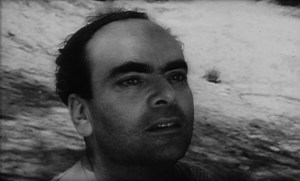

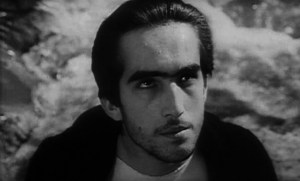

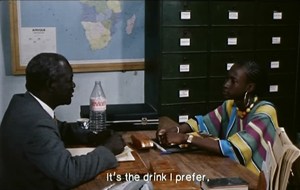

To watch older films is to engage in an act of archaeology. Boudu is an old film that offers evidence of another time and place (even another place for modern Parisians). One aspect of Boudu is the arrangement and development of action in dynamic space through ensemble staging and longer takes. I imagine that the average shot length (ASL) for Boudu is around 15 seconds, much longer than the ASL of most films today. Here we have a scene in which Renoir plays with the arrangement of the characters (four characters) in space (a single room) over the course of a complete scene.

In a wide shot (WS) M. Lestingois and Boudu talk at the table. Boudu gets up and walks over to a post and leans against it.

We cut to a medium close up (MCU) of Boudu. This edit, as are all the others in this scene, are both large jumps from WS to MCU and yet are fully beholden to the rules of continuity. In other words, although the edit suddenly brings us in close, we accept it as a seemless moment of the film.

Now the camera is back at the WS and Mme. Lestingois enters.

Boudu walks around the far side of the table and leans on it. We cut to a medium shot (MS) showing Mme. Lestingois behind Boudu. This offers a nice opportunity for Boudu to express his thoughts and Mme. Lestingois to show us her reactions. There is also a nice sense of depth in the framing.

Now back to the WS.

Then another big jump to an MCU to focus our attention on the interplay between M. Lestingois and Boudu.

According to Bordwell (The Way Hollywood Tells It, 2006), as cinematic techniques and practices changed over time, past techniques and practices have been lost. Bordwell argues for what he calls intensified continuity where the ASL has dramtically shortened and where action moves forward through editing rather than developing through space over time. What we have lost is the tendcy to stage action with an ensemble of of characters, each playing off each other, editing and shot framing emphasizing the action/reaction between characters, and even gradation or levels of meaning with each shot. Here in Boudu we see Renoir following the older techniques, one might say more theatrical techniques, of a more static camera, longer takes, ensemble staging, and a clearly defined space in which the action can take place. For better or for worse, rarely do filmakers shoot this way anymore.

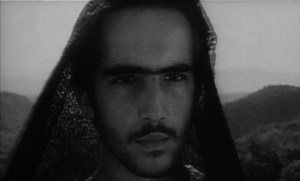

Another great little moment in Bouduis this dinner scene in shich the action is down the hall from the camera. Here the maid leans over the Lestingois’ table and picks up a plate. The camera begins to truck left as the maid also walks to our left.

And then the maid stops in the kitchen and takes off her appron. We see here through two indows that look out onto a courtyard.