We live is an age of great abundance for many. And yet, so many struggle for basic things, like shelter. Many of us, though not particularly wealthy by Western/Northern standards (I live in the U.S.), still live like kings compared to much of the rest of the world. And yet, sometimes we still know (I still know), at times, the struggle just to get by, especially those of us who have tried to support a family on a meager paycheck.

With those thoughts/experiences in mind (sometimes buried, sometimes glaring) I watched a fascinating documentary on La maison de Jean Prouvé (part of a great 4 DVD series called Architectures by ARTE France, distributed in the U.S. by Facets Video). I was struck by the simple story of a man who lost his business, faced into a difficult financial crisis, and had to then find appropriate shelter for his large family. His solution was to build on land others said could not be built on, use prefabricated pieces, ask his friends for help, and do it quick and cheep. What Prouvé created became one of the most famous, yet modest dwellings of the 20th century. The house is also both a challenge and an inspiration to me and my aspirations for someday designing my own house. But it is more than merely a question of design.

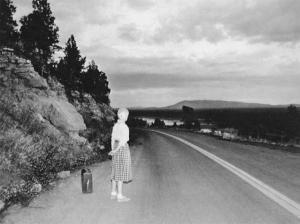

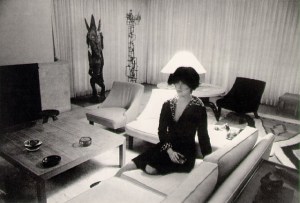

A few pictures will give some idea of the concept by way of the reality.

As one can tell, the house is simple, though not exactly austere; the design is modern, though far from being overrun with ideology; and the space is very economical, giving what needs to be given without giving too much. It is truly an economy of means.

What I also like was how communal and personal the building became, and how it became that way out of necessity. Photos show the Prouvés and their friends hauling materials up the steep hills, laying foundations, putting up walls, and helping the Prouvés reach their goals.

My own philosophy, though still rather unformed, ranges toward the modern and the simple. I love quality and innovation. I also love the challenge, but so too do I love the finished product that can then be enjoyed. Although there are many aspects of Prouvé’s house I would do different, I often think about how much I have and want in contrast to what I actually need.

I believe design and art are central to the human spirit. I am only willing to give up beauty when it is absolutely necessary, and only for temporary periods, for beauty is like air. Some will not find Prouvé’s house to be a work of beauty. To each her/his own. For my part I find tremendous beauty in the simplicity and design of this house, but I also see an acceptance of one’s place in the world. Prouvé was able to achieve both. Live within your means, that is a kind of beauty too.

Jean Prouvé built his house in 1953. I find it an interesting coincidence that I began recently watching Eric Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales. Rohmer began directing the loosely connect series in 1962. I won’t attempt an overview of Rohmer’s life or a critique of his films, but I will say that I find his circumstances of production to be equally as fascinating at those of Jean Prouvé.

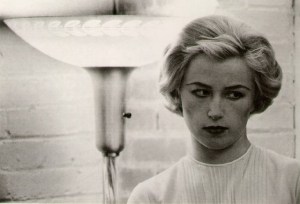

In the beginning Rohmer had no money to make films. He had written one novel and then some stories. He was unhappy with how the stories turned out and he felt he needed to make them into films to adequately get across his ideas. Eventually he got what he needed, but only just. His films, especially the early ones, are excellent examples of an economy of means. He shot on a shoestring budget, often using small crews and working with friends. He also tended to shoot in limited takes and tended to prefer first takes. He rehearsed his actors relentlessly and then tried to not let them ask for more takes. Sometimes he used improvisation during rehearsals, but rarely in production. His first feature-length film, La Collectionneus (1967), was shot at less than a 2:1 ratio, which means that most of the takes were at most done twice, and many only once.

Rohmer’s first of his moral tales, La Boulangère de Monceau (1963), was shot MOS (silent), dubbing the audio in later and relying mostly on voice-over, on 16mm format, using found locations. Never released in theaters, this 20 minutes film was almost more of an experiment in style and production, but it clear set the tone for the later films.

Here is a brief look at the filming/story telling style of Rhomer. While we hear a voice-over we watch a simple moment based mostly on looks and glances that are fuller of meaning than the rather unemotional surface gloss might suggest.

When I compare Rohmer and Prouvé I see two driven men, singular in their ideas and ideals, producing great artifacts within strenuous limitations. I also see a mode of production, whether by choice or by acceptance, that is truly independent from larger financial/corporate interests. No one is completely independent, but smaller scales of production, working with friends and colleagues, forced to stay focused on the end goal, and beholden more to one’s own vision than to those of others, makes Rohmer’s moral tales and Prouvé’s family dwelling about as independent as one could hope for.

Some might say that Prouvé’s home is too simple and lacks too much. Some might say that watching Rohmer’s films is like watching paint dry. I know it is a matter of taste, but sometimes I would like to believe that not all taste is equal. Certainly, I find the final products of these two men more satisfying than so much else in this world. And that is what I look for in my own “limited means” life.