Without an element of cruelty at the root of every spectacle, the theater is not possible. In our present state of degeneration it is through the skin that metaphysics must be made to re-enter our minds

~Antonin Artaud, Theatre and its Double (1938)

To interpret a text is not to give it a (more or less justified, more or less free) meaning, but on the contrary to appreciate what plural constitutes it.

~Roland Barthes, S/Z, (1970, trans. 1974)

You have seen No Country for Old Men and you liked it. You have read the reviews and their obligatory references to Javier Bardem’s hairdo. You may have even noticed how much this film draws from all the other Coen brothers’ films, both stylistically and thematically. But what is most interesting to my limited sensibilities is the film’s ability to give us something that seems entirely new while yet existing within the conventions of classical Hollywood narrative.

And then, on the other hand, No Country for Old Men gains power by thwarting classical narrative through subversions to plot expectations, through dreams, and through the character of Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem). Chigurh is a driving force, like the character of Frank Miller in High Noon (1952) who is coming to bring death upon the marshall, or General Zaroff in Connell’s The Most Dangerous Game (1924) who relentlessly hunts his human prey, or the terminator in The Terminator (1984) bent only on the destruction of Sarah Connor. Chigurh is also a psychological enigma, like Norman Bates of Psycho (1960) or Michael Myers in Halloween (1978). It is this second aspect, that of the psychological enigma, that thwarts the narrative.

For classical narrative to function it requires characters who can be understood, both in terms of their psychologies and in terms of their actions. According to Bordwell (1985):

The classical Hollywood film presents psychologically defined individuals who struggle to solve a clear-cut problem or to attain specific goals. In the course of this struggle, the characters enter into conflict with others or with external circumstances. The story ends with a decisive victory or defeat, a resolution of the problem and a clear achievement or nonachievement of the goals. The principle causal agency is thus the character, a discriminated individual endowed with a consistent batch of evident traits, qualities, and behaviors. (p. 157)

Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin) is our protagonist. He is the most specified character and the primary causal agent. He is who the audience identifies with, and for whom the audience roots. His actions, that of finding the satchel of drug money and deciding he could take it and get away with it, are what compel the story forward. His hold on the satchel is not unlike the monkey who puts his hand in the jar, grabs the shiny object, and then cannot get his fist out of the narrow opening. Chigurh is the antagonist. He exists to thwart Moss. He is the relentless, unstoppable force. But his psychological makeup is a mystery. We have trouble guessing what he might be thinking. As sheriff Ed Tom Bell says, Chigurh is more like a ghost than anything.

After we have been introduced to the landscape via the beautiful opening shots of the film, and after we have been introduced to the killer Chigurh, we are introduced to Llewelyn Moss. The landscape proscribes the stage on which the action begins. It also functions as the “undisturbed stage” (Bordwell, 1985, p. 157) from which “the disturbance, the struggle, and the elimination of the disturbance” issue forth. Chigurh has, so far, only been shown as a killer. As he strangles the deputy we see Chigurh’s face ecstatic to the point of rapture. One might conclude Chigurh’s ecstasy is psychologically defining, that may be, but he remains, in narrative terms, a simple character. Llewelyn Moss, on the other hand, is given carefully determined narrational moments that flesh out who he is, what kind of person he is, and define him as more fully human rather than as a stock protagonist.

When we first see Llewelyn Moss he is hunting antelope. This is how the film introduces us to Moss:

Moss looks through the scope of his hunting rifle. He has a seriousness about him. He is a hunter. He aims for the largest of the male antelopes. He shoots, but the animals run away. Now he has to track them.

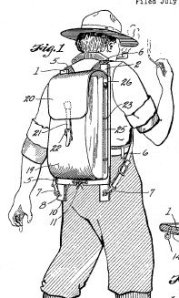

The fact that he is using a traditional hunting rifle says a lot. In our world of available hi-tech weaponry where men are typically fascinated with military-style armaments, Moss caries a rifle from another world. This rifle has a wood stock, is bolt action, and mounts a typical hunting scope. It is also a .270 caliber, which is a classic round for antelope hunting.

Here is the description from the book by Cormac McCarthy:

The rifle strapped over his shoulder with a harnessleather sling was a heavybarreled .270 on a ’98 Mauser action with a laminated stock of maple and walnut. It carried a Unertl telescopic sight of the same power as the binoculars. The antelope were a little under a mile away.

Moss wears a plaid shirt with sleeves rolled up. He is working class in appearance. The color of his shirt, skin, and rifle blend in with the light brown of the desert landscape. He is a man in his element. There is something about him and this desert environment that are similar.

He also wears a white hat. In the tradition of the western genre there is no wardrobe choice more conspicuous than the white hat for the good guy and the black hat for the bad guy. Ghigurh does not wear a hat, but he sports and undeniably conspicuous hairdo that effectively functions as a “black hat.”

The hat (hats have played significant roles in other Coen films) situates Moss in the mythological West. Moss is presented as a kind of cowboy. Chigurh is presented as something other. This contrast will feel a little like that of the old world versus the new world in Lonely are the Brave (1962) and, like the story in that film, the cowboy loses.

It must be highlighted that our first glimpse of Moss has him with a gun. This denotes him as a killer. Moss “as killer” is a critical characteristic. The contrast between the killer Moss and the killer Chigurh will become the ground for the narrative’s causality.

This scene also denotes Moss as hunter, which is different than killer. The story will turn this characteristic on it head and makes Moss the hunted. We might assume, then, that Moss will become something like Rambo in First Blood (1982).

After Moss fires his shot the antelope run away. He stands up and watches them run off. He then does something interesting. He bends over, picks up the empty shell from his expended round and puts the shell in his shirt pocket.

My father is a hunter. I grew up hunting with him, although I personally haven’t hunted in years. My father is the kind of hunter who likes tradition and economy. He likes true hunting rifles rather than the popular militaristic styles. He saves his shell casings so he can reload his own rounds. He will carefully measure the gunpowder into each shell casing and then seat a particular bullet into the shell. Notes are taken for future adjustments. Quality and exactness are critical. Different kinds of bullet and powder combos are tested. Choices are made based on what game will be in the sights. It is a kind of primal craft, something from the past. My father has often said he was born a hundred years too late.

Moss represents that past. He is the archetype of the self-sufficient, frontier man who can live off the land, live by his wits, and take care of himself no matter what comes. He is the man’s man of the Zane Grey novel or John Ford film. He is the dream of the West. He is an incarnation of John McClane (Die Hard). His character remains consistent throughout the film to that archetype.

The simple detail of Moss picking up the shell and putting it in his pocket tells us a lot about him. He is a kind of craftsman. He is thoughtful and meticulous. He lives out a kind of economy of not wasting even the littlest thing. This economy will make him a formidable foe for Chigurh. Unfortunately for him, his wife, and others, Chigurh is more than just a bad guy – he is a force of nature, like the coming of darkness or the second law of thermodynamics.

But what makes up this darkness? Death eventually comes to all. Chigurh does not increase death, for death is total for every generation. But Chigurh is relentless. He is, in Lyotard’s words, a monad – a self-contained entity only aware of his own concerns. Lyotard (1991) says of the monad: “When the point is to extend the capacities of the monad it seems reasonable to abandon, or even actively to destroy, those parts of the human race which appear superfluous, useless for that goal. For example the populations of the Third World” (p. 76-77). In this sense Chigurh might be seen as symbolic of larger cultural forces, such as the ruthless drive of capitalism or empire. Or he might be just a tornado.

It is not merely that Chigurh is a bringer of death. Or even that he is like the character of Death in Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957), which he also is. Chigurh represents the deep human fear of chance as destiny. With Chigurh every choice becomes and existential choice, and the chooser never has all the information. Characters have choices, but those choices, like all choices, are ultimately about who one is and who one will be. However, those characters don’t always realize the profound nature of their choices. All to often human beings live their lives as though in a dream. Consider this famous scene:

Anton Chigurh

Call it.

Gas Station Proprietor

Call it?

Anton Chigurh

Yes.

Gas Station Proprietor

For what?

Anton Chigurh

Just call it.

Gas Station Proprietor

Well, we need to know what we’re calling it for here.

Anton Chigurh

You need to call it. I can’t call it for you. It wouldn’t be fair.

Gas Station Proprietor

I didn’t put nothin’ up.

Anton Chigurh

Yes, you did. You’ve been putting it up your whole life you just didn’t know it. You know what date is on this coin?

Gas Station Proprietor

No.

Anton Chigurh

1958. It’s been traveling twenty-two years to get here. And now it’s here. And it’s either heads or tails. And you have to say. Call it.

Gas Station Proprietor

Look, I need to know what I stand to win.

Anton Chigurh

Everything.

“You’ve been putting it up your whole life you just didn’t know it.” That just might be the most important line of the film. A man’s life is a story, true, but it is a mix of choice and chance. Like the journey of the coin, and of what the coin represents: a choice between heads or tales. But what kind of choice is that? One chooses, but chance decides. The gas station proprietor chooses heads and it is heads. He gets to keep on living for now. Does he know the nature of his choice? Do we know the nature of our choices? Of course, like Lazarus being raised from the dead, the gas station proprietor has not been save from death, it will still come, it is inevitable.

So where does this leave us? No Country for Old Men gives us a story of characters, of the choices they make, of the consequences of those choices, all set within a consistently circumscribed world. And yet, at the end, where are we?

Sheriff Ed Tom Bell is our narrator. Llewelyn Moss is our protagonist. Anton Chigurh is our antagonist. The stage was undisturbed, a disturbance occurred, and struggle ensued. But the classical narrative runs dry; it does not seem to be able to sustain itself. Why? There are at least three reasons.

1) Moss, rather suddenly, ends up dead. After following his struggle so closely and with so much detail the narration leaves out his last struggle. We do not see him die. His corpse lies on the floor of his hotel room before the film is finished with its story. This death, though later in the story than the death of Marion Crane in Psycho (1960), still comes too early to be a climax. And yet it would seem the final confrontation between Chigurh and Moss was what the film was building up to. But no, the audience is left hanging, as it were, in the wind.

2) Chigurh is a cypher, a ghost. We know he is odd, probably psychotic. We know he is a ruthless killer. We know he is tough and maybe impossible to kill. But what do we really know about him? Almost nothing. What is his motivation? Money? No. Power? Maybe. Principles? We are told yes, but are we sure, and what principles exactly? And is he really a part of the world as presented to us? Or is he part of a different world? On more than one occasion the lives of those who come in contact with Chigurh depend on whether they “see” him.

Nervous Accountant

Are you going to shoot me?

Anton Chigurh

That depends. Do you see me?

One could take this to mean that if one does not talk one lives. On the other hand, to see Chigurh is to believe in ghosts. The last shot of him shows him walking away down a sidewalk. We know he is sure to get away, he always does.

What an interesting shot. It is so bland, so ordinary, just an ordinary street. He is the figure of death resuming his journeys. This last image of Chigurh then slowly dissolves to a profoundly troubled and puzzled Ed Tom Bell.

3) Ed Tom Bell’s has two dreams. It is possible that just about anything is easier to interpret and understand than a person’s dreams. Ending the film with two (not just one) dreams produces a number of potentialities of meanings upon meanings. Certainly there is a weight to the dreams, but they are naturally vague and open. The film stands at the precipice of being plural, that is, it hinges on the possibility of an infinity of meanings, which means it could have no meaning. Consider the dreams:

Loretta Bell

How’d you sleep?

Ed Tom Bell

I don’t know. Had dreams.

Loretta Bell

Well you got time for ’em now. Anythin’ interesting?

Ed Tom Bell

They always is to the party concerned.

Loretta Bell

Ed Tom, I’ll be polite.

Ed Tom Bell

Alright then. Two of ’em. Both had my father in ’em . It’s peculiar. I’m older now then he ever was by twenty years. So in a sense he’s the younger man. Anyway, first one I don’t remember to well but it was about meeting him in town somewhere, he’s gonna give me some money. I think I lost it. The second one, it was like we was both back in older times and I was on horseback goin’ through the mountains of a night. Goin’ through this pass in the mountains. It was cold and there was snow on the ground and he rode past me and kept on goin’. Never said nothin’ goin’ by. He just rode on past… and he had his blanket wrapped around him and his head down and when he rode past I seen he was carryin’ fire in a horn the way people used to do and I could see the horn from the light inside of it. ‘Bout the color of the moon. And in the dream I knew that he was goin’ on ahead and he was fixin’ to make a fire somewhere out there in all that dark and all that cold, and I knew that whenever I got there he would be there. And then I woke up.

What do we have here? I believe there is meaning here. I believe that we can tease out what McCarthy and what the Coens are getting at. But we do so without finality. We find layers, complexity, multiplicities, and contradictions. In other words

No Country for old Men ends but it does not resolve. Lack of a clear resolution saws off, as it were, the possibility of a classical narrative ending.

In structure No Country for Old Men proceeds largely by way of a classical narrative, but it also has elements of, and ends by way of art-cinema narration. These two narrational modes are logically at odds with each other. According to Bordwell (1985):

For the classical cinema, rooted in the popular novel, short story, and well-made drama of the late nineteenth century, “reality” is assumed to be a tacit coherence among events, a consistency and clarity of individual identity. Realistic motivation corroborates the compositional motivation achieved through cause and effect. But art-cinema narration, taking its cue from literary modernism, questions such a definition of the real: the world’s laws may not be knowable, personal psychology may be indeterminate. (p. 206)

Ed Tom Bell’s confusion at the end is also our confusion. What disturbs him is not merely the extreme violence he has witnessed. He is confounded by his inability to understand the world anymore. He has assumed, and been hoping for, a clear resolution to life. He has taken for granted a meaning to the universe and come up woefully short.

“And then I woke up.” Ed Tom Bell is how awake. He has been living in a kind of dream his whole life. He has been wagering his existence his whole life and he just didn’t know it. Now he knows it, but he has no answers. His eyes are finally open but the scene before him is indecipherable. The extreme violence he has witnessed compares to the narrative violence, that is, to the deep rupture to the classical narrative expectations he was expecting. These two violences have caused metaphysics, as it were, to re-enter his mind. His presuppositions have been stripped. He sees life for what it is not. He is lost in a world of choice and chance.

. . . and that’s one way of looking at this polysemous film.

References:

Bordwell, D. (1985). Narration in the fiction film. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Lyotard, J. F. (1991). The inhuman: Reflections on time. (trans. G. Bennington & R. Bowlby). Oxford: Blackwell.