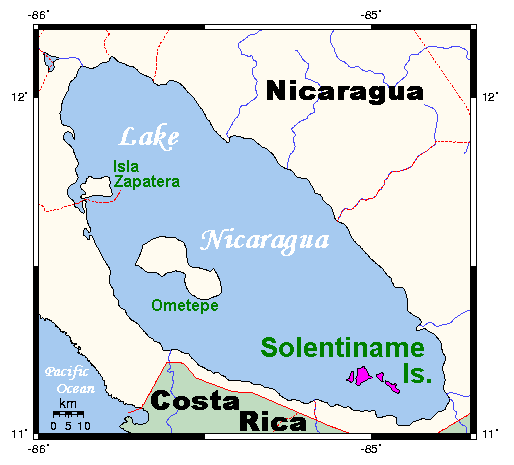

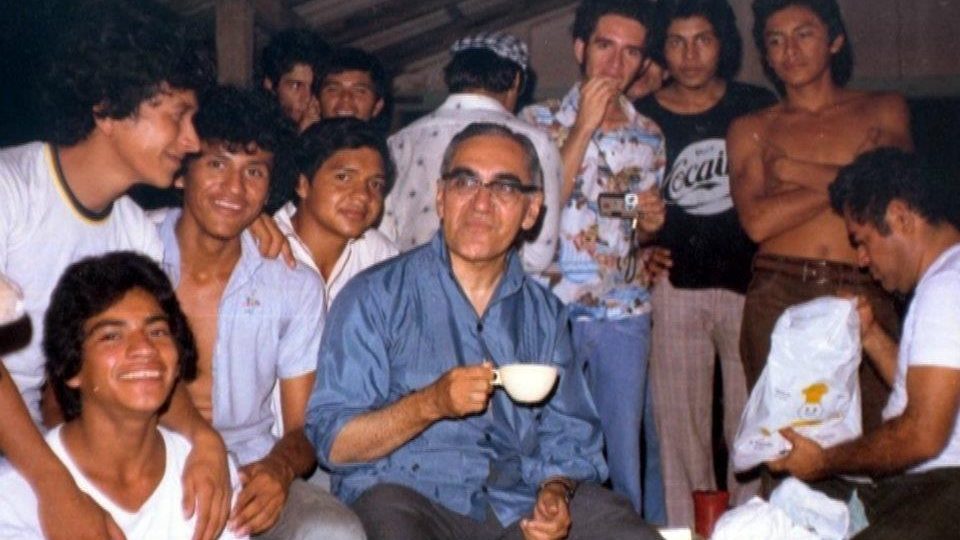

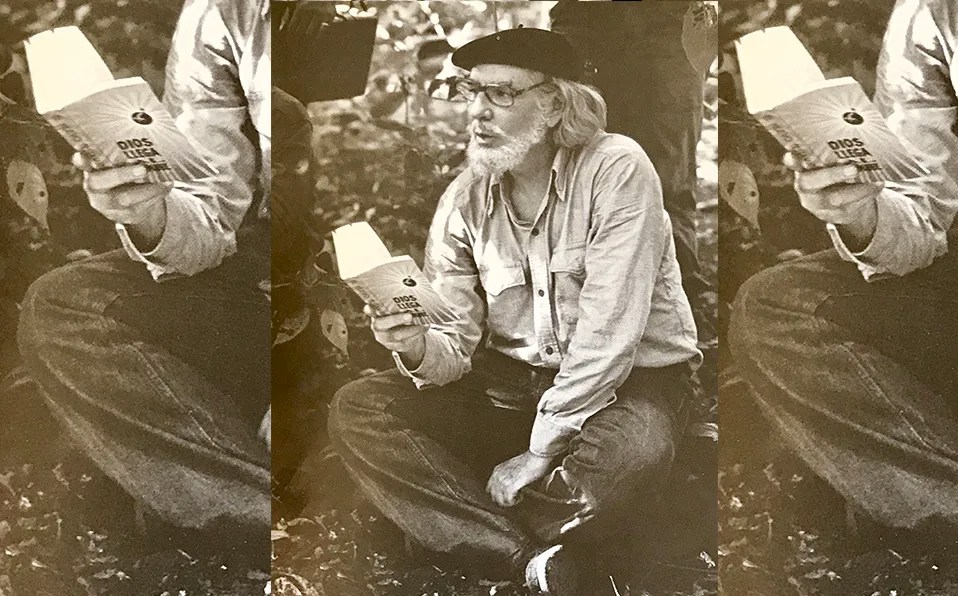

In the mid-to-late 1970’s, over a period of years, a group of campesinos (peasant farmers) in Solentiname, an archipelago in Lake Nicaragua, gathered together to read and discuss the teaching of Jesus. They focused on the beatitudes from the Gospel of St. Matthew. Below is a small excerpt from their larger discussion, facilitated by Ernesto Cardenal. This discussion occurred during the brutal dictatorship of the Somoza family and the long Nicaraguan civil war. In the end the Sandinistas overthrew the Somoza dictatorship.

Let’s go now to the southern islands of Lake Nicaragua and read from The Gospel in Solentiname.1

Dichosos los que tienen espíritu de pobres,

porque de ellos es el reino de los cielos.

Blessed are the poor in spirit,

for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

ALEJANDRO: “[…] The poor who are bourgeois, who are opposed to revolutionary changes, they do not have compassion in their hearts, and they are not the poor of the Gospel.”

LAUREANO: “A perfect communism is what the Gospel wants.”

PANCHO, who is very conservative, said angrily: “Does that meant that Jesus was a communist?”

JULIO said: “The communists have preached what the Gospel preached, that people should be equal and that they all should live as brothers and sisters. Laureano is speaking of the communism of Jesus Christ.”

And PANCHO, still angry: “The fact is that not even Laureano himself can explain to me what communism is. I’m sure he can’t.”

[Ernesto Cardenal] said to PANCHO: “Your idea of communism comes from the official newspaper or radio stations, that communism’s a bunch of murderers and bandits. But the communists try to achieve a perfect society where each one contributes his labor and receives according to his needs. Laureano finds that in the Gospels they were already teaching that. You can refuse to accept communist ideology but you do have to accept what you have here in the Gospels. And you might be satisfied with this communism of the Gospels.”

PANCHO: “Excuse me, but do you mean that if we are guided by the word of God we are communists?”

[Ernesto]: “In that sense, yes, because we seek the same perfect society. And also because we are against exploitation, against capitalism.”

REBECA: “If we come together as God wishes, yes. Communism is an equal society. The word ‘communist’ means community. And so if we all come together as God wishes, we are all communists, all equal.”

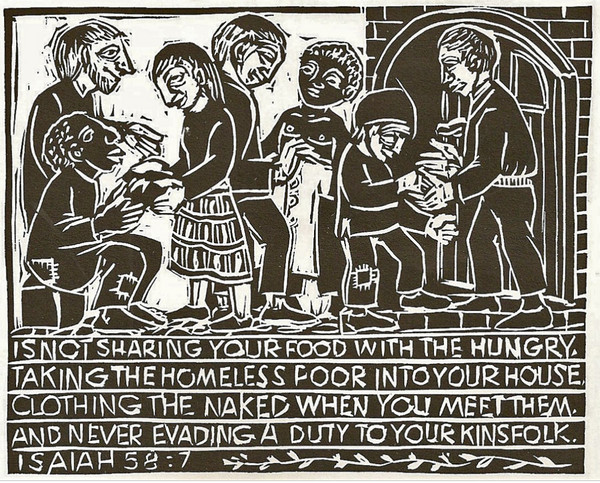

WILLIAM: “That’s what the first Christians practiced, who had everything in common.”

PANCHO: “I believe that communism is a failure.”

TOMAS: “Well, communism, the kind you hear about, is one thing. But this Communism, that we should love each other…”

PANCHO: “Enough of that!”

REBECA: “It is community. Communism is community.”

TOMAS: “This communism says: Love your neighbor as you love yourself.”

PANCHO: “But every communist speaks against all the others. That means they don’t love each other.”

ELVIS: “No, man. None of them talk that way, man. They do tell us their programs. And they’re fine.”

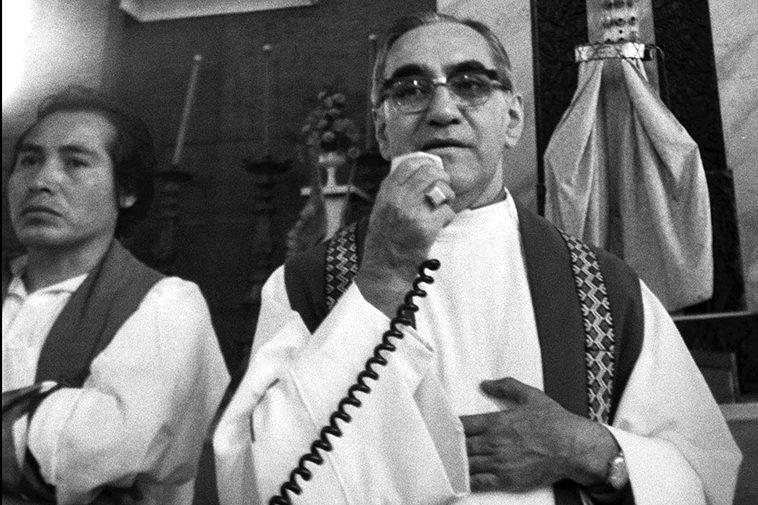

Increasingly, I’ve come to see the Gospels in a way similar to these Nicaraguans do. I used to think somewhat similarly to Pancho, who can only see equating Christianity and communism as outrageous. But I now see there is a kind of communism at the heart of the good news of Christ. In fact, I’m inclined to think it’s the communism; all others are imitations in degree, some very dark indeed, but others have been closer to the Gospel. But Christ must be the center and all other things ordered to Him, that is, to love itself. And unlike some Catholic apologists who publicly argue that a person cannot be both Catholic and a socialist (which is provably false), I’m inclined to go the other way – to be Catholic is to be, in one way or another, a socialist and perhaps even more specifically a communist (a distinct form of socialism). One can argue that without Christ at the center any form of communism will fail, but also one can argue that with Christ at the center then communism is inevitable. In this I empathize with Cardenal who did not waver in his conscience or commitments after being publicly reprimanded by Pope John Paul II:

“Christ led me to Marx,” Father Cardenal said in an interview in 1984. “I don’t think the pope understands Marxism. For me, the four gospels are all equally communist. I’m a Marxist who believes in God, follows Christ, and is a revolutionary for the sake of his kingdom.”2

Although I don’t call myself a Marxist (yet) because I don’t like overly loaded terms and I don’t want to be labeled an “ist” anything, I do find the use of Marxism as a social science useful in helping us get at the roots of economic inequalities and forms of alienation that both plague our societies today and are what Jesus preached against. And I find many of the core goals of communism at least interesting in the light of the Gospel. Long before communism came into existence as an ideology, I find Scripture pointing in that direction, especially in terms of liberation and freedom. In short, “liberation theology is nothing other than theological reflection on oppression and on the people’s commitment to freedom from this oppression[.]”3 I find this a fundamental and essential Catholic pursuit. But who am I? I’ve still got so much to figure out.

The Gospel in Solentiname has been a revelation for me. Jesus and His disciples were more like the Nicaraguans in Solentiname than the Americans in my neighborhood or parish. The insights from these campesinos, I believe, are closer to the kinds of insights one would expect from those listening directly to Jesus, or those of William Herzog in his book, Parables as Subversive Speech, than those spoken in a homily on the beatitudes in the tradition of Christendom. They are earthy, human, sensitive to the struggles of liberation, arising from a place of poverty, and more concerned with how to love one’s neighbor than in one’s interior spiritual attitude or a personal psychological definition of faith. In other words, they don’t overly “spiritualize” the Gospels but, in fact, more clearly preach the Gospel as it was delivered and heard two thousand years ago.

I am not willing to say the insights found in The Gospel in Solentiname are unproblematic, but they are refreshing in their frankness and challenging in their non-bourgeois perspective. They also highlight something important that I think many of us have lost—that basic human need to read and discuss the Scriptures with others in a kind of dialectical circle of interpretations. We Catholics tended to be trapped in a prison house of pedigreed teaching and official interpretations that we fear stepping out and taking the risk of speaking our own interpretations born from our own lives. But if we step back we discover the Church (if not, for example, Catholic Twitter) has a rich tradition of multivalent perspectives and rarely provides singular interpretations of Scriptural passages. Personally, I long for a Solentiname discussion group. What a joy it would be.

Finally, the last member of the group to speak was a person named Elvis. I believe this is Elvis Chaverría, a member of the Solentiname community and a revolutionary guerrilla in the fight for freedom. On October 13, 1977…

Nicaragua’s leftist guerrillas, the Sandinista National Liberation Front (F.S.L.N.), thought to have been decimated by years of repression, launched a new military offensive against the Somoza regime, attacking National Guard barracks at Ocotal in the north and San Carlos in the south, losing two rebels but killing two dozen soldiers.4

One of those two rebels killed was Elvis Chaverría who was involved in the attack at San Carlos. He “was captured during the raid on San Carlos, taken up the Río Frío, and shot in the head.”5 That attack precipitated the beginning of the end for the Somoza regime. Elvis is remembered as a hero and a martyr of the revolution. He gave his life in the struggle to bring about a more just society for his neighbors.

1Ernesto Cardenal, The Gospel in Solentiname, trans. Donald D. Walsh (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2010), 122-123.

2Elia E. Lopez, “Ernesto Cardenal, Nicaraguan Priest, Poet and Revolutionary, Dies at 95,” The New York Times (The New York Times, March 1, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/01/world/americas/ernesto-cardenal-dead.html.

3David Inczauskis, “Once I Discovered Liberation Theology, I Couldn’t Be Catholic without It,” America Magazine, June 4, 2021, https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2021/06/04/liberation-theology-catholic-faith-240599.

4“National Mutiny in Nicaragua,” The New York Times (The New York Times, July 30, 1978), https://www.nytimes.com/1978/07/30/archives/national-mutiny-in-nicaragua-nicaragua.html.

5Sarah Gilbert, “Revolutionary Trails in Nicaragua,” Wanderlust, accessed July 6, 2022, https://www.wanderlust.co.uk/content/travels-in-nicaragua/.