>40 years ago today the first two nodes of what would become the ARPANET were interconnected between UCLA’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and SRI International in Menlo Park, California. ARPANET was the birth of what we now call the Internet.

Author: Tucker

>marshall mcluhan

The spiritual disciplines of a married woman

Typically one does not go to Godard seeking a spiritual film. Not that his films are devoid of spiritual concerns (his 1985 film Je vous salue, Marie deals directly with spiritual concerns) but Tarkovsky or Bresson or Kieslowski are more typical choices for spiritual cinema. On the other hand, through a different lens as it were, Godard is a very spiritual director, particularly when it comes to his critiques of modern society. On the surface he catalogs – in his own dry humor – the many phenomena of our strange and extravagant late-industrial culture with all of its gaudy materialism, its objects, and its fetishes. And yet are not his characters often living out their new modern spirituality in a sea of things, words, actions, violence, sex, love, books, images, ideas, advertising, and every other signifier of something other? That something other may, in fact, be faith. The question, then, is what is this modern faith?

Godard’s cinema has always been a cinema de jour. His emerges from the endless world of the now. In this age where “God is dead” the drive within each of us for meaning, and finding that meaning in relation to something outside of ourselves, has not gone away. If we find no God we will make one, and as is always the case, we fashion our gods according to our own needs and desires, and in our own image. We then adopt forms of spiritual disciplines that serve our image of God and the imagined requirements of our new spirituality.

What is a spiritual discipline? There are numerous definitions but, in short, a spiritual discipline is a habit or regular pattern of specific actions repeatedly observed in order to bring one into closer relation to God and to what God desires for one to know. It is something one does as an act of devotion and a means of advancement or growth.

How do we see this playing itself out in Godard’s films? In À bout de souffle (1960), a paean to the Hollywood gangster film, Michel exhibits a kind of ritualistic and constant homage to the film gangster archetype, Humphrey Bogart. He goes through the motions, adopts character traits, tropes, stylistic postures, and language to inhabit the ideal of his film hero. His focus and devotion are fundamentally religious, and his actions play out like spiritual disciplines – immature and humorous at times, but spiritual disciplines nonetheless. What Godard gives us in his unique way is a portrait of the spiritual status of French youth in 1960. In a world where traditional religious options fade they are replaced by a new religion, that of the cinema. In the end Michel dies as a martyr to his faith.

In Une femme mariée: Suite de fragments d’un film tourné en 1964 (1964) Godard presents another kind of spirituality, that of the sexual body in a consumeristic world. Although sexuality is one of the oldest “religions” in human history Godard examines it within a thoroughly modern context. Charlotte, who is married to one man and in love with another, is juggling her relationships while gauging herself against the constant inputs she receives (accepts, seeks) from advertising – in particular, advertisements about female beauty and, especially, those pertaining to the ideal bust. Her life becomes a constant calculation of actions – maybe motions is a better word – to present herself both to the world and to herself. She becomes both priestess and offering at the altar of modern woman.

One scene in the film highlights Charlotte’s commitments. Here she is finishing her bath.

She meditates (on what we do not know) with perhaps an intelligent expression, perhaps vacuous. She exits the bath. The camera followers her legs. She dries off.

She then used scissors to trim her leg hair.

Then trims her already carefully coiffed locks.

She then trims her pubic hair.

The camera does not follow the scissors, but we hear them and assume she is not trimming her bellybutton hair.

European films of the 1960s gained a reputation in the U.S. for being risqué. Though tame by today’s standards, to have a woman trim her pubic hair, even if only suggested, would have called attention to itself, and Godard makes sure the camera holds long enough for us to notice. Within the context of the film this shot makes a great deal of sense. Her bathing and grooming, and the calling attention to the details of her actions present to us the actions of her spirituality, her disciplines. This is not a world without a god, rather it is a world of many gods (her husband worships airplanes and is a pilot) and her god is a combination of love, sex, her body, her image as woman, etc. In this quiet moment we are voyeurs to her prayer, to her communion.

More than Godard’s other films of this era Une femme mariée is a highly formalized, stylish, and unusually crafted visual fugue of body parts, actions and gestures, and environments. At times we are drawn toward comparisons with Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928) for its uncompromising formalism and spiritual quest of its protagonist, and to Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) also for its formalism, sexuality and the spiritual struggle of its characters in light of nuclear weapons. Godard takes the next step to characterize the spiritual quest of the modern woman (we should included men as well, though that is sometimes debatable with Godard) as neither traditionally religious/Christian or driven by existential terror, rather the new spirituality is a commodity based religion of self-image mediated through the world of late industrial production and consumerism. What makes this work, and elevates the film, is that Godard’s characters do not suffer the anguish of extreme religious piety or existential nihilism, rather they fully inhabit their world as accepting individuals who embrace the proscriptions of their circumstances – like peasants in medieval Europe, like good 20th century bourgeoisie.

In this way Godard stands as one of the more significant artists of the late modern/post-modern period. Later he would take these themes to greater and more political heights with such films as 2 ou 3 choses que je sais d’elle (1967) and Weekend (1967). Godard, though thoroughly materialistic, may also be a more spiritual director than most – a consideration we do not consider enough.

>brother can you spare a taser?

>We glorify the protests of the past. We have seen (or remember) the civil rights marches, the sit-ins and other actions. We remember the anti-war movement. We remember May 1968 and other important dates. But where are we today? Remember the huge global anti-war protests just prior to the invasion of Iraq. Or the mass protests at the Republican convention. Remember the police crackdown on the protesters? It was like clockwork, surgical, carefully crafted like extraordinary rendition. But it also got violent at times – the anti-riot police were the ones who typically led with the violence. And recently we saw the same thing at the G20 protests in Pittsburgh. But, like the protests of the romantic past, we once again wonder at the role of the police and the individual choices of each officer.

Check out this video and ask yourself what is really going on.

Now read this excerpt from a news report on National Public Radio regarding the G20 summit and, specifically, the protests outside the summit.

ROBERT SIEGEL (host): And have the protests been going on throughout the entire city?

SCOTT DETROW (on scene reporter): They have. After the tear gas, the march broke into many small groups. It stayed out of downtown, from what we can tell. Police are responding by breaking up these clumps of protesters. I saw one after the tear gas was fired. They were peacefully marching down the street and police officers swarmed the block from all directions. They got out of the car and they just pushed the protesters into side streets, and that’s what they’ve been doing. There have been arrests here and there, we’re hearing from other news outlets. But that seems to only be happening when marchers are directly confronting police officers. For the most part, police are just trying to show a presence and trying to get these marchers to break up on their own.

I find both the video clip and the NPR report fascinating, not because they are anything special, but because they say a lot about the structures of power that we have come to view as normal. But should they be normal? Consider the situation: A group of representatives from the richest and most powerful nations on earth come together to discuss the future for all of us. But the the G20 has been around for some time already and the world is in trouble with widening gaps between rich and poor, increasing corporate control over such basic things as water rights, food distribution, farmer’s crops, and of course the economy. In fact, it could be said the recent bailouts of large companies around the world represent a kind of coup d’état. It may just be that the current economic crisis (and the steps to remedy it with tax dollars) is evidence of the increasing loss of real power on the part of the government (a government of the people) over the economic/big business sector.

Consider this exchange from Michael Moore’s Capitalism a Love Story:

MICHAEL MOORE: We’re here to get the money back for the American People. Do you think it’s too harsh to call what has happened here a coup d’état? A financial coup d’état?

MARCY KAPTUR (Representative from Ohio): That’s, no. Because I think that’s what’s happened. Um, a financial coup d’état?

MICHAEL MOORE: Yeah.

MARCY KAPTUR: I could agree with that. I could agree with that. Because the people here really aren’t in charge. Wall Street is in charge.

Given our democratic ideals the situation looks grim. One could easily see the recent election as a kind of sham (as are most elections but especially this one), a game those in power managed in order to help all of us feel like we participated in their power play. Maybe democracy as it’s been sold to us is a way to tie us up with mythological fairly tales so that the powerful few remain in power. So why would not people peacefully (or even angrily) march down the streets where the G20 is being held to protest? And why wouldn’t those marchers see the police as something like turncoats?

And this brings me to more questions: Why do police (working class men and women apparently there to uphold basic freedoms of speech, especially when it is most needed) seem to automatically view protesters and demonstrators as enemies and radical provocateurs? Are they trained to think that way? Or is it something closer to social influence and group think? Why, when anti-riot forces come out in overwhelming force, they end up being the group most prone to violence? Could it be something like the old adage, ‘to the man with a hammer every problem looks like a nail?’

Why does our society accept as normal such activities as the use of tear gas, batons, knocking people to the ground, tasers and rubber bullets, and now anti-riot siren devices, by police against weaponless, non-violent protesters? What is the psychology?

I won’t pretend to have the answers to these questions. However, when I see the way the police in this country deal with protesters I cannot help but be reminded of some very famous sociological studies, horrific events, and historic observations. My point here is not to equate actions so much as highlighting the way the human mind works in various situations.

- Milgram experiment: Showing that people will do terrible things as long as someone (preferably someone “official”) tells them to.

- Stanford prison experiment: Demonstrated the impressionability and obedience of people when provided with an apparently legitimizing ideology along with social and institutional support.

- My Lai Massacre: Showing that individuals are capable of anything when part of a group, following orders blindly (as soldiers and police are trained to do), and operating in a tense situation outside of normal experience.

- Banality of evil: Hannah Arendt’s observation that evil acts are most typically carried out by ordinary people viewing their actions as normal.

- Social influence: How we are all greatly influenced by others around us, the situation we are in, and tendencies we have toward self preservation, being liked, and not being stigmatized.

I have come to believe the actions of police toward protesters reflects aspects of all these sociological and psychological characteristics found in the list above – though to a substantially lesser degree in some cases. But there is one other factor that possibly plays to largest role, that of hegemony.

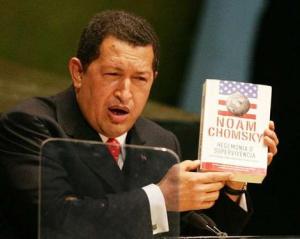

Now hegemony is a good college level word for why people acquiesce, and even embrace, the power structures that control, and even sometimes enslave, them. If you did not study the word in college you may remember when Hugo Chavez touted the book Hegemony or Survival: America’s Quest for Global Dominance by Noam Chomsky when he spoke at the U.N.

Chavez aside, the concept of hegemony, first proposed by Antonio Gramsci as a way of trying to understand why the working classes did not rise up against their oppressors as the Marxists predicted, is a way to understand how the powerful persuade the less powerful to adopt the values of the ruling class. We live in a country that denies the existence of class structures in terms of power. We speak of middle class or working class merely as sympathetic terms used by politicians to manipulate votes. We do not accept the concept of a ruling class, but maybe we should.

In the videos on this page look at the faces of the police (the ones not wearing Darth Vader masks). There is a lot of anger in their eyes. I wonder if the anger comes from an internal struggle. I can only hope. I imagine the police feel a tension between the hierarchies of power they have come to believe must be protected (of which they are sworn to uphold) and their deeply internal sense of humanity and their belief in democracy (an understanding of which was probably formed in grade school like it was for most of us). They are caught in the clash of values, but they are a group operating with broad impunity and supported by the social dynamic of being able to hide within the apparent pawnship of their job. So they continue to manhandle, arrest, and attack the protesters. But their anger gives them away. They are alienated from the power they protect, and suppressing the very voices that are pointing out that alienation. That would make just about anyone angry.

Consider this video of another protest. If not for the police intervention it would almost be humorous.

I cannot imagine a less threatening protest. In fact I find it almost comical. Why then the overwhelming police force? Are they afraid of another Battle in Seattle? Clearly this is an example of those in power acting out of fear, but what do they fear? In fact, the whole thing has a kind of choreographed arc that not only speaks of a profound lack of imagination on both sides, but indicates the protest may be as much a product of hegemony as the police presence.

What do we do with all this? First, we should not romanticize the past. The efforts of the civil rights and anti-war movements of the past were often heroic, but they were also brutal and scary at times. People were seriously hurt and some died. Many went to prison. And we should know that external actions come from what is inside, but also know that one’s external actions affects one’s soul. The police who give in to the psychosis of power, abuse other humans, act out of anger, and stand in the way of freedoms that are not given by governments but only taken away, those police are damaging their own souls. And they are human just like me – frail, prone to delusion, living in a powerful culture, needed to be loved, and wanting to do what is right. We should not feel sorry for them, but we should empathize.

The fact is many of the above sociological/psychological concerns raised about police action can apply to the protesters. At times it appears some of the protesters are seeking to recreate a May ’68 kind of experience for their own pleasure. I wonder how many made the effort to reach out to the police in the days or weeks prior to their marches. I wonder how many pre-judged the police as irredeemable, in part because it is both the easier route and less romantic than manning the barricades. This is one reason that, while I support the protesters in general, I think the predictable protests outside every G20, G7, World Bank, etc., meeting may be as much a symbol of failure as righteous anger. We need more than theater, we need transformation.

Finally, we are all in this thing called life together, whether we want to admit that or not. It’s easy to march, easy to crack skulls, and very easy to write blog posts, and it’s difficult to love, forbear, and forgive.

>Tim McCaskell explains Neoliberalism

The Gospel of Supply Side Jesus

Thank you Al Franken, thank you.

Who inherits the earth?

Protesters outside the G20 in Pittsburgh

demanding fundamental change.

Consider these quotes:

“The great and chief end…of men’s uniting into commonwealths and putting themselves under government, is the preservation of their property.”

~ John Locke, 1689“But as the necessity of civil government gradually grows up with the acquisition of valuable property, so the principal causes which naturally introduce subordination gradually grow up with the growth of that valuable property.”

~ Adam Smith, 1776“Till there be property there can be no government, the very end of which is to secure wealth, and to defend the rich from the poor.”

~ Adam Smith, 1776

Pittsburgh police, defending the rich

from the poor at the G20.

If you didn’t know who wrote these words you might think they were from the pen of Karl Marx. Interesting. More substantive than economic systems and their ideologies (and their debates) is the concentration of power and its supporting hegemonies. In other words its all about who inherits the earth and how they keep it. Little do they know…

“Blessed are the gentle, for they shall inherit the earth. ”

~ Jesus, c. 30

The gentle, or meek, have a different relationship to property and wealth than those who climb over others to make the world their own. It is not that they do not want the world, it is that they recognize having the world for their own is not worth being the kind of person who has no interest in loving others as their primary motivation. To love the world is to give up loving people. It is not a good trade – no matter how free the market. Gaining the world is not worth a lousy character, and no amount of economic ideology can convince otherwise.

Questions of character are always personal, but what about our institutions of power? We live in a world that places a kind of sacred halo around the idea of private property. We know that the Declaration of Independence almost contained the phrase “life, liberty and the protection of property.” I don’t want anyone to take my home away from me, but I have to think that the ownership of property and all its attendant rights (real or perceived) only gets understood as sacred in a world that has turned its back on truth. The irony is not merely that to gain the whole world is to lose one’s soul, but also to gain one’s soul is to gain the world.

There is that old adage that all governments lie. It is just as true that governments, first and foremost, exist to protect the haves and the things they own. Only secondarily, and usually through great struggle, are benefits secured for the have-nots.

I stand, in spirit, with the protesters who call for change and accountability from our governments and the captains of industry. I stand against the obvious seeking of power and influence for selfish ends. I stand against clearcutting forests and mountain top removal mining, and against the pollution of our air and water, and against insurance companies managing our healthcare, and subsidies to weapons manufacturers and to farmers of vast genetically modified monocultures. And I stand against the use of violence to solve problems, such as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. (The list can go on and on.) On the other hand, I cannot demand that those in power give up the world, as it were, so that I might have it instead. Though my power and influence is small, I am not morally superior than they. Rather, they must give up the world because it does not belong to them.

>Žižek on Children of Men

>

Slavoj Žižek raises his arms.

I wrote a Personal Response to Children of Men, which has received quite a few hits since its posting. I recently came across Slavoj Žižek’s brief commentary on the film here. I think you will find it interesting at least. Žižek is a fascinating cat and one of the more entertaining philosophers.

>This break is called the electro fffunk daddy superstar break

>Just in case you found my previous post too esoteric or your French a little rusty, here is something to cleanse the palate.

[Thank you Andrew & Toby for bringing this to my attention.]

>Czesław Miłosz interviews in French

>