Several days ago I watched les carabiniers (Godard, 1963) and I have not been able to get it out of my head since. I won’t go into the details of the story since it’s a film widely known, and I know I should have seen it ages ago, but it’s one of those films that I just passed over, until now. I truly enjoyed the film and I was struck by one scene, for me the most important scene of the film, and the mental connections it produced for me.

[Side note: One thing that I find somewhat interesting is that when one is analyzing a Godard film, one is aware that Godard knows you are analyzing it.]

The scene is where the carabiniers execute the young Marxist woman. Now this film is a dark comedy, and is obnoxiously (but I love it!) so throughout, but this particular scene has a moment of real pathos and poignancy.

The young woman has been caught by the carabiniers and is put in front of the ad hoc firing squad. She has already had a chance to espouse some Marxist philosophy only to make the commander upset. The men raise their rifles and get ready to shoot.

However, the woman, with her head covered by a handkerchief, begins to repeat slowly “brothers,” “brothers,” “brothers,” “brothers.”

The men have trouble with her simple pleas. Several times their guns waver. Something inside them responds to the reality that they are all brothers in a bigger struggle. The handkerchief is then taken off her head and she recites a parable from Mayakovsky. But finally, they shoot and she is dies. But she doesn’t die quick enough, so as she lies on the ground a soldiers says she is still moving…

…while another repeatedly pulls the trigger.

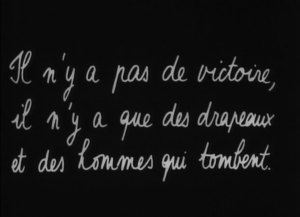

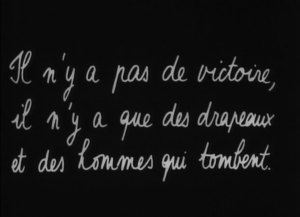

Finally, the scene ends with this quote:

il n’y a pas de victoire

il n’y a que de drapeaux

et des hommes qui tombe

“There is no victory

There are only flags

and fallen men”

In the context of the film this scene shows the extent to which the carabiniers have been brainwashed by their government – the king himself has asked them to do what they do, or so they believe. The scene also extends outward to the whole reality of war, of cinematic depictions of war, and to our present day. For me there is a mental connection with the final scene in Full Metal Jacketwhen the American soldiers come face to face with the young female Vietnamese sniper. As she lies on the floor of the shattered building, mortally wounded and writhing in pain, the soldiers stand around discussing her fate.

A portion of that scene goes like this:

The SNIPER gasps, whimpers.

DONLON stares at her.

DONLON

What’s she saying?

JOKER

(after a pause)

She’s praying.

T.H.E. ROCK

No more boom-boom for this baby-san. There’s

nothing we can do for her. She’s dead meat.

ANIMAL MOTHER stares down at the SNIPER.

ANIMAL MOTHER

Okay. Let’s get the f**k outta here.

JOKER

What about her?

ANIMAL MOTHER

F**k her. Let her rot.

The SNIPER prays in Vietnamese.

JOKER

We can’t just leave her here.

ANIMAL MOTHER

Hey, asshole … Cowboy’s wasted. You’re fresh out

of friends. I’m running this squad now and

I say we leave the gook for the mother-lovin’ rats.

JOKER stares at ANIMAL MOTHER.

JOKER

I’m not trying to run this squad. I’m just

saying we can’t leave her like this.

ANIMAL MOTHER looks down at the SNIPER.

SNIPER

(whimpering)

Sh . . . sh-shoot . . . me. Shoot . . . me.

ANIMAL MOTHER looks at JOKER.

ANIMAL MOTHER

If you want to waste her, go on, waste her.

JOKER looks at the SNIPER.

The four men look at JOKER.

SNIPER

(gasping)

Shoot . . . me . . . shoot . . . me.

JOKER slowly lifts his pistol and looks into her eyes.

SNIPER

Shoot . . . me.

JOKER jerks the trigger.

BANG!

The four men are silent.

JOKER stares down at the dead girl.

There is a bit more dialogue, and then the final scene is of the soldiers walking through the war ravaged terrain singing the theme from the Mickey Mouse Club.

The connection with les carabiniers is not merely that you have a bunch of men killing a solitary, young female. Although that is both powerful and telling in each case. For me the connection is the fact that in each film the female represents a person of character, not necessarily for good or evil, but for something higher and bigger than either the shallow materialistic goals of the soldiers in les carabiniers, or the shallow and aimless goals(?) of the soldiers in Full Metal Jacket. In les carabiniers the young revolutionary quotes Lenin and Mayakovsky. She appeals to their common brotherhood. She willing goes to her death (maybe she didn’t have a choice). In Full Metal Jacket the young sniper is in her own country, fighting for her beliefs and, most telling, she prays. The soldiers of Full Metal Jacket, as is made clear throughout the film, are almost soulless products of American consumer culture fighting from within their own nihilistic world. This contact they have with a soulful, spiritual human being has no impact on them.

What I believe is happening here in Full Metal Jacket is a description of how horrible and damaging war is to the soldiers who are involved – not just physically, but spiritually. A more typical modern interpretation of the experience of war is what we find in Platoon. In that film the characters witness the horrors of war, and yet the film still manages to find a way for those involved to grow as people. The Charlie Sheen character speaks of at least learning something valuable at the end, regardless of how bad it got. Full Metal Jacket does not grant such notions. Here soldiers are emotionally and psychologically damaged, just as though they have lost limbs. There is no going back. There is no coming to terms with what they have done, or are doing. I find this perspective to be rather profound, especially in light of a number of the stories coming out of the U.S. occupation of Iraq.

Then there is another connection in the web of meaning, that is the film Why We Fight (2005) which I also watched recently and highly recommend. Could it be that today (maybe always) war is a financial venture on the part of big business in collusion with big government? For those who have been paying attention, this is an old question. But just in case anyone missed it, Why We Fight takes a close look at the hows and whys of war-mongering.

Some salient points in the film:

A slightly younger Dick Cheney hammering out U.S. foreign policy and pulling political strings:

Cheney then gets hired as CEO of Halliburton. His personal wealth skyrockets from less than a million $ to many, many millions of $$$ in just three years. He uses his political connections to get business for Halliburton.

The defense industry makes it money from war mongering – as long as politicians are for war then the defense contractors make their money, and apparently they like lots of money.

Now Cheney is Vice President. The people of the U.S. elected a defense contractor as second in command!

Donald Rumsfeld greets Saddam Hussein, promising friendship, political backing, and weapons of mass destruction for the war against Iran.

[The popular saying in Washington D.C. before no weapons of mass destruction were found in Iraq was, “We know he has weapons of mass destruction, we have the receipts.”]

Just a few years later tens of thousands of Iraqi civilians die, and many more are seriously wounded, by the U.S. military “shock and awe” strike against the Iraqi people – including thousands of children.

And the only true interest the U.S. has in the region is the vast oil reserves.

Now Iran is in the crosshairs.

I cannot help but think that those who are willing to sacrifice something while being sent off to war are caught between mythologies of nobility and the real motivations of those who send them off to war. Are not modern “carabiniers” promised much the same kinds of things promised to those in les carabiniers? Are these not the realities of “surge” and “sacrifice?” Is it not, truly, a dance of death?

A final note: I love the connection that Godard makes with Chaplin’s The Great Dictator. Notice the sign of the “Double Cross” on the dictator’s hat with the crosses on the hats of the carabiniers in the image at the beginning of this post. Wonderful!