If you can forgive me, which you must, then you will understand I blog much of the time for my own selfish edification and education. This is one of those times.

I do not know much about the history of modern German cinema. But I am interested. In my more brilliant moments I might say something like “the present is always built on the past.” How true that is! On the DVD extras for the Criterion release of Ali: Fear Eats the Soul there is a short documentary by the BBC called Signs of Vigorous Life: New German Cinema (1976). From today’s perspective one might say the film is about how one person’s past is another person’s present is another person’s future. On the other hand, the film is also about breaking with the past and creating something genuinely new and authentic.

Now, this documentary is not at all dazzling, but it does focus on several filmmakers (Fassbinder, Schlöndorff, Wenders, Herzog) who exemplified the New German Cinema, as it is called. These filmmakers continue to influence film history and other filmmakers on numerous levels. Ironically, it is the one filmmaker who died too young that may still have the most influence.

One thing that filmmakers like to do when the camera is turned on them is to talk. Especially if talking is a means of saying what is wrong with the world and what it is that filmmaker is uniquely doing to change it. We get some of that in this film. New German Cinema began, like most all of the “new” cinemas, in and around the early 1960s, which was a time all about what was wrong world and how to fix it. (It still should be in my opinion.)

The group of filmmakers featured in this documentary are/were part of the second generation of the New German Cinema. The first generation never achieved quite the level of critical acclaim, financial success, or notoriety as the second, but it did establish a kind of vision that, though not exactly marching orders, did point to the future. This vision, expressed in writing, is known as the Oberhausen Manifesto, with with the old film was declared dead – Der alte Film ist tot. (I’ve included the manifesto below.)

Whether the second generation was influenced directly by the manifesto is debatable.

L’enfant terrible

Two shots of Fassbinder on the set somewhere in the 1970s:

Fassbinder on the set of Berlin Alexanderplatz two years before his death:

Two images of a dishelved Fassbinder from Wenders’ film Room 666 (1982):

Room 666 was shot in May of 1982 at the Cannes film festival. Fassbinder died on June 10, 1982.

What do I think of Fassbinder? I am troubled by him. I no longer hold the romantic view of artists that I once did, so I cannot look at his life and swoon over how beautifully tragic is was. And yet I know that his drug use, high energy, promiscuity, etc., played a huge part in the creation of his art – and I love his films. The BDR trilogy ranks for me as a pinnacle of filmmaking. I cannot wait to get my hands on Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980).

I have a feeling that Fassbinder might have made an annoying friend, one of those friends that you cannot let go of and yet you’re always shaking your head at wondering when he is going to excavate himself from the mess of his life. Of course, I only know of him from what I’ve read, which is quite limited, so maybe his excesses got all the press and there is more to him than that.

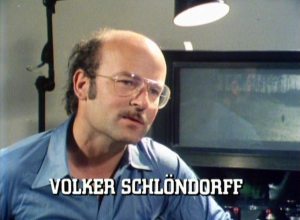

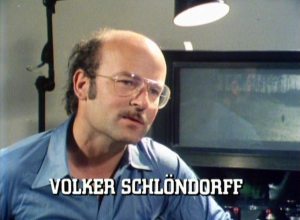

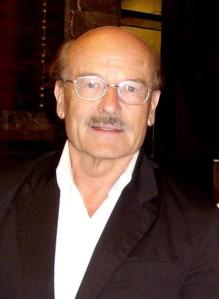

The Brain

Schlöndorff confers with someone on the set somewhere in the 1970s:

Schlöndorff now:

What do I think of Schlöndorff? I cannot speak of Schlöndorff with any authority. I have only seen part of The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum (1975) – which I thought was incredible, but need to finish. I have not seen The Tin Drum (1979), which looks really heavy. I did see his version of Death of a Salesman (1985), which I loved, as well as the documentary about the making of the film. Any recommendations as to which of his films I should see I welcome.

Somehow I think that having Schlöndorff over for dinner would be an evening of interesting conversation. But I imagine he would be the kind of guest to sneak into the kitchen and nibble on the food before it’s brought out.

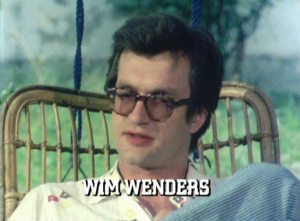

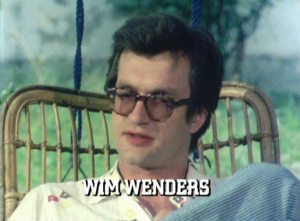

The Metro-Intellectual

Wenders looks through the camera for a moving shot on Kings of the Road:

Wenders now:

Wenders discusses using music in his films, a failed attempt to work with Radiohead on a film, and his past collaborations with U2:

What do I think of Wenders? I have been a big fan of his for years. A number of his films I love, and a number I like despite their flaws. In the 1980s I “found” him, and his films were part of the introduction I received into the world of non-U.S. films. I do have an issue with him though: Wenders has a way of letting a certain hipness get in the way of going as deep philosophically as his films seem to promise. I feel that he, like Woody Allen, often comes up to the precipice and then turns away. And yet, Wenders has so often captured the post-war German angst on film as good, or better, than anyone. And I find that angst to be far more universal than nationalistic. I can see myself in his characters. That may be why I gravitate to his films so much.

I can imagine that if Wenders was staying over as a house guest one would have great conversations about the relationship between images and one’s identity in the post-modern world. One would also have to tell him to stop video taping everything.

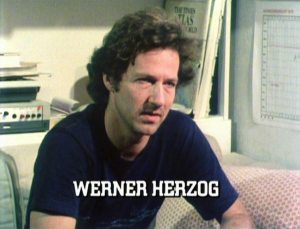

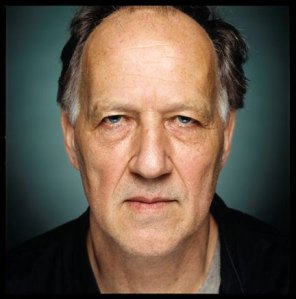

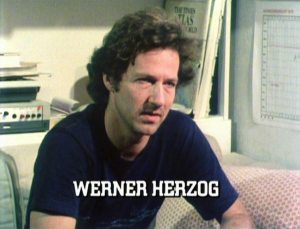

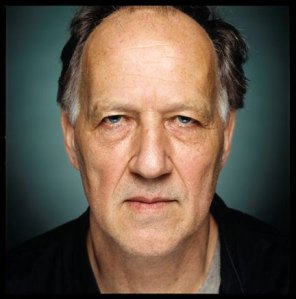

Mr. Serious

It has been a while since I have seen any of Herzog’s films. I certainly have not kept up with his more recent efforts.

Herzog scouts locations somewhere in the 1970s:

Herzog now (looking more and more like Pete Townshend):

After losing a bet to filmmaker Errol Morris, Herzog eats his own shoe:

What he’s after:

What do I think of Herzog? For me Herzog might be the best of the bunch, but it might be a toss up with Fassbinder. Herzog’s films, especially from the 1970s, are a combination of classical narrative and significant boundary pushing. I was blow away when I saw Stroszeck (1977), Aguirre: The Wrath of God (1972), The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974), and Fitzcarraldo (1982). All films I need to revisit soon.

On the other hand, I think Herzog is probably the kind of house guest who would take off his shoes and socks as soon as he sat down in one’s livingroom, and then complain about working with actors and producers. On the other hand he probably is very funny when he gets a little drunk.

Conclusion:

My soul resonates with many of the films of the New German Cinema. There is often a sense of emptiness, of being lost, of trying to find one’s way in the darkness, that I see in my own life. There is also a sense that there is something darker and less life-giving under the shinier aspects of society. I know this to be true. I am not a morose person, and yet I am inclined more towards a glass-half-full perspective, as my wife will remind me. In that respect the New German Cinema seems more authentic and true to me.

Oberhausen Manifesto

The collapse of the conventional German film finally removes the economic basis for a mode of filmmaking whose attitude and practice we reject. With it the new film has a chance to come to life.

German short films by young authors, directors, and producers have in recent years received a large number of prizes at international festivals and gained the recognition of international critics. These works and these successes show that the future of the German film lies in the hands of those who have proven that they speak a new film language.

Just as in other countries, the short film has become in Germany a school and experimental basis for the feature film. We declare our intention to create the new German feature film.

This new film needs new freedoms. Freedom from the conventions of the established industry. Freedom from the outside influence of commercial partners. Freedom from the control of special interest groups.

We have concrete intellectual, formal, and economic conceptions about the production of the new German film. We are as a collective prepared to take economic risks.

The old film is dead. We believe in the new one.

Oberhausen, February 28, 1962

Oberhausen Manifesto discussion forum 1962