Category: movies

15 slates from The Searchers

A couple of days ago I had the pleasure of watching The Searchers with my daughter Lily. She had seen a couple of other westerns previously, but this was her first time with The Searchers. Afterwords we talked about it. We talked about the character of Ethan Edwards and the complexity of his character. We talked about how the native Americans were portrayed and the historical reality of the genocide against them. We also watched the extra features and talked about how the film was created. I mentioned that many consider it to be one of the best westerns ever made. Lily said it IS the best western ever made. She’s my kid!

>that wonderful uncle

>

I am reminded again why Jacques Tati is one of my favorite filmmakers. Recently I sat down with my daughter Lily and we watched Mon Oncle (1958). This film is considered Tati’s best film by many, and it truly is a masterwork of the artform. Although my heart leans more towards Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday (1953), I still love Mon Oncle – and so does Lily. I must say both films are glorious.

As I was pondering why Tati’s films endear themselves to my sensibilities so, I thought of Jean Renoir. Renoir may be my favorite director, if I could actually have such a thing. What grabs me and holds me fast about Renoir’s film is their unabashed portrayal and love of humanity. Tati, though more stylized in his aesthetic, has the same generous and loving characteristic. Tati’s characters are closer to types than Renoir’s, but they are types as only the French can do them – a kind of multifaceted simplicity of forgiven sinners.

With this love of humanity in mind I was struck afresh by the opening credits. They stand out as an example of creatively dealing with two problems: 1) How can the credits actually be an entertaining part of the film rather than something merely tacked on? and 2) How can the credits actually contribute to the meaning of the film?

As the film opens we catch a glimpse of a construction site and hear construction noises. In the left foreground are signs with name on them. As I understand it, these signs correspond to the common practice of placing signs with the architect’s name and builder’s name on the construction site. We soon realize these names, however, are of the “architects” and “builders” of the film we are watching. It is both a clever and interesting way to present the film’s credits. It also says something about the story we are about to see and the kind of filmmaker who is giving us this film.

By juxtaposing the film’s “construction crew” with an actual building construction site the viewer is asked to see the film’s crew as laborers and collaborators. This film is a product of human effort, creativity, sacrifice, and love. Tati’s name is last, but not last as it is with most films for the purpose of being more prominent. Tati has set himself within the circle of collaborators. Yes, it is his film, but it is their film too.

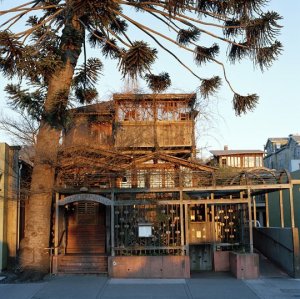

And then we cut to this:

The other world: Decay as Life

To my mind this is one of the great edits in cinema. Still within the credit sequence, we have the juxtaposition of this shot with the previous which loads it up with meaning – a meaning that the rest of the film will explore. We have gone from the new to the old, from a world of freshly built to a world of decay, from life as death to death as life – for it is in this world of decay that we witness the vibrant bustle of humanity interacting with itself rather than with machines and objects. Mon Oncle is a meditation on these two worlds. As we will see, buildings and houses, which are evidences of human activity and intention, seem to stand for the people who inhabit them. In other words, the artifice becomes the humanity. Thus, this run down street, which exudes a deep and flawed beauty, is the truer humanity.

Tati plays Hulot, and one can assume Tati loves Hulot for all his bumbling and goodheartedness. But Tati’s name, as per the credits, is associated with the new, the world of construction and building, the forever present. Hulot, the oncle of the title, is instantly associated with the old and crumbling. It is as though Tati recognizes that he lives and works in the modern world but finds himself reaching back vicariously to another, more romantic time and place. Hulot then may be his avatar as well as his clown.

I’m not the only fan of Jacques Tati. So is Frank Black:

I will now consider Frank a close friend.

>goodbye good man

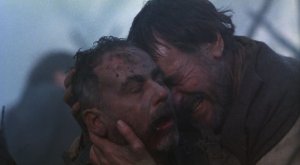

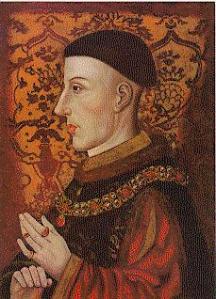

Henry V

Good king Henry V sporting a

popular haircut of the day.

I haven’t been blogging as much about movies lately, and that’s for a number of reasons, mostly because it’s been Summer and we’ve been outside more than in, and also because I’ve been picking up books more than films. Now the leaves are beginning to turn and we are watching a few more films. Recently Lily and I watched Kenneth Branagh’s brilliant Henry V (1989). This was not Lily’s first Shakespeare, but it’s one of her first, and maybe her first not directed for kids. A few times we paused and I explained what was going on, or who was who, but for the most the part the film is easy to follow. More than this, it is a powerful play with great scenes, and great dialogue and speeches. But what struck me the most this time was how it portrayed war.

War is terrible. The great battle in Henry V comes right after one of the English language’s greatest rallying speeches – the St. Crispin’s Day speech. From the speech we get the title for Band of Brothers. In that speech young king Henry rallies his troops with promises of glory and honor, of future stories and brotherhood. That speech spins a aura of wonder and excitement around the coming battle. But then we get into the battle and it is awful. I am thankful Branagh took that opportunity to de-glorify war somewhat.

I was a little concerned showing Lily this film because of both the war images and the difficulty of the language, but I’m glad I did. We talked about the gruesomeness of the fighting and what that means. She and I have also talked numerous times about how films are made and that movie blood is really red paint, etc., so she gets it, but still images do move the soul.

Here are just a few of the many images of the horror, sadness, ugliness, and suffering of war from Henry V:

Of course the English win that war and they do go on to bask in a kind of earthly glory. Such are the lives of victors. But I hope I never forget the great gulf there is between speeches made about war and war itself – even if the speeches be written by the Bard himself and the battles won. I always want to remember that political speeches about the sacrifices made by soldiers and their families are easy to give.

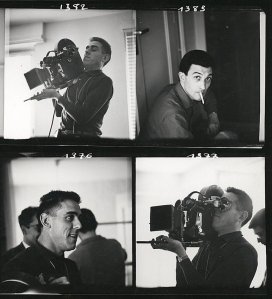

faves: cinematographers

The camera takes center as Cocteau directs.

I became more interested in cinema when I began to understand the various working parts of the medium. My interest especially took off when I started to grasp the idea of cinematography and the role of the cinematographer. This growing realization came upon me sometime during my undergraduate years. Like the music connoisseur who finds new albums by seeing which musicians are listed in the credits and then following the trail, I began to find films based on who shot them. If I liked the cinematography of Apocalypse Now (1979), I would see that it was shot by Vittorio Storaro, and that fact would lead me to the films of Bernardo Bertolucci. Or I could look for a kind of aesthetic story by tracing a cinematographer’s oeuvre, such as Robby Müller shooting the great early films of Wim Wenders, for example Alice in the Cities (1974) and The American Friend (1977), and then shooting Repo Man (1984), and then To Live and Die in L.A. (1985), and then Down By Law (1986).

Recently I noticed something about myself as well. The cinematic image is like a drug for me. In fact I am frequently more moved, and more intrigued, by the images on the screen than the stories they tell. Narrative is often not my main reason for watching and liking films. I watch films in much the same way that I walk through a gallery or museum, going from one art work to the next, tying them together in my mind, creating connections. As the images move and shift in a film I take in each shot like the paintings in a gallery. Maybe this is because I was a professional photographer for a number of years. Or maybe that’s why I became a photographer.

With cinema the images are part of a narrative, and I do find the way those images serve the narrative to be interesting as well. But it’s still the images that get me first. The story is the excuse for their existence. I can’t say that’s a good approach to watching films, but I can’t help it. I guess I am wired that way. That may also explain why learning about cinematography and cinematographers opened up my appreciation of cinema as a whole.

Here is a list of some of my favorite cinematographers. These are the ones who’s work have most influenced my appreciation of cinema. Needles to say, there are many more I could and should list, but then it just gets unwieldy. There is so much great work out there. I have broken the list up into two groups, not as a designation of quality or capability, but of the place each has played in my development. The list is also not ranked. They could go in just about any order.

GROUP ONE:

Freddie Young

There may be no more significant film in my cinephiliac development than Lawrence of Arabia (1962), which was the first of Young’s three academy awards for best cinematography. The other two were for Doctor Zhivago (1965) and Ryan’s Daughter (1970). But look at his other films, like: Treasure Island (1950), Lust for Life (1956), The Inn of the Sixth Happiness (1958), and You Only Live Twice (1967). Beautiful stuff.

Raoul Coutard

Coutard was THE cinematographer most closely associated with la nouvelle vague and, in particular, Jean-Luc Godard. He shot Breathless (1960), of course, but take a look at his list and you’ll see a what’s what of ground breaking films, including Week End (1967), maybe the most significant work of art in the latter half of the 20th century.

Vittorio Storaro

Storaro may have been the first cinematographer that I really noticed for what he did. For a while he was my favorite. His films include such seminal works as The Conformist (1970), The Spider’s Strategem (1970), Last Tango in Paris (1972), 1900 (1976), Reds (1981), Ladyhawke (1985), The Last Emporer (1987), and many others. He also has won three academy awards for best cinematography.

Robby Müller

Robby Müller does not get considered enough in the U.S. But look at his film list! I already mentioned some films above, others include The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick (1972), Kings of the Road (1976), Paris Texas (1984), Dead Man (1994), Breaking the Waves (1996), Dancer in the Dark (2000), Coffee and Cigarettes (2003), and many more. His work with Wim Wenders was seminal in my development. All that angst was just what I needed at that time. Sometimes I still do.

Néstor Almendros

For me it was a revelation to discover Almendros was the cinematographer for Eric Rohmer. Some of those films includes such greats as La Collectionneuse (1967), My Night at Maud’s (1969), Claire’s Knee (1970), Chloé in the Afternoon (1972), and more. He was also the cinematographer for Truffaut. Some of those films inlcude Two English Girls (1971), The Man who Loved Women (1977), and The Last Metro (1980). But he also shot Days of Heaven (1978) which is stunningly lensed.

Sven Nykvist

Ah Sven. There are few filmmakers that have had as much influence on me as Ingmar Bergman, and Nykvist was his primary cinematographer. I don’t need to list those films, you know them. He also shot Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice (1986) and Allen’s Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989).

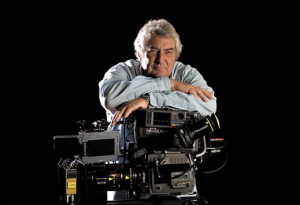

Roger Deakins

Deakins is almost the defacto shooter for the Coens. He started with them back on Barton Fink (1991). Before that conspiracy he shot Sid and Nancy (1986) and Mountains of the Moon (1990). He also lensed Passion Fish (1992), The Shawshank Redemption (1994), Kundun (1997), and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007), plus a lot of other wonderful films.

GROUP TWO:

Henri Alekan

I first heard of Alekan by way of Wings of Desire (1987). Only later did I realize that he photographed such great films as Beauty and the Beast (1946) and Roman Holiday (1953).

Dean Semler

For me Semler is the guy who shot The Road Warrior (1981). I can hardly think of a better way to use a camera than to build a cage around it, put it in the middle of the road and then, while its running, crash a car into it. That’ll give the guys at the lab heart palpitations, or at least it did back then.

Vadim Yusov

Yusov was the early cinematographer for Andre Tarkovsky. He and Tarkovsky cut their teeth together. His most famous film was Andrey Rublyov (1969). But Solyaris (1972) is worth a gander (as are all of Tarkovsky’s films). Tarkovsky is my second favorite filmmaker, right behind Jean Renoir. Or maybe they’re tied.

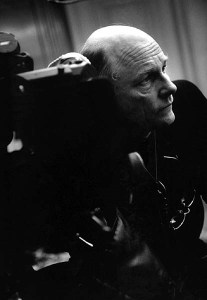

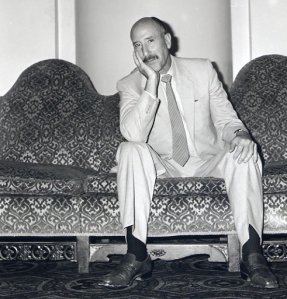

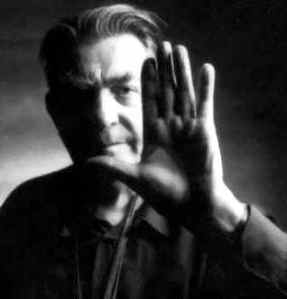

Karl Freund

I already wrote a post about Freund. Check it out. Don’t you just love that picture?

Many of these cinematographers are rather long in the tooth and several have passed on. Many were long past their prime by the time I “discovered” them. Fortunately their work survives and still lives. I have not been keeping up with the newer crowd who are re-setting the standards. But my point here was to list off those who played a part in my earlier development as a lover of cinema. I cannot say how many I have left off the list, but it is a lot. I hope you have your favorites as well.

without roof or law

What is the difference between a dead body and a nearly dead person? Is it not a great gulf? Is not that gulf as great as the distance between the furthest stars and even further? That’s obvious, but strangely we can forget. People become topics of conversation, objects of judgement, things to behold. We put people in boxes, including ourselves.We simplify our world by simplifying each other. But it is a survival tactic that leads to death.

Agnes Varda’s film Sans toit ni loi (1985), translated as “without roof or law” (English title Vagabond), begins with a dead body, but ends with a living, breathing, suffering, confused, crying, dying human. And in that difference is the true power of the film.

Like Citizen Kane or Sunset Blvd, Sans toit ni loi begins with a body (or death), and the story that follows is the story of that body. Varda has not made an easy film. The story is episodic, but the arc of the main character is not really an arc as much as a steadily sloping line downwards to the right. But we have seen these kinds of stories before, the inevitable demise of a person as their life tragically spirals towards tragedy or death. In that light Sans toit ni loi could be understood as a meditation on nihilism. But I don’t think it is only that.

Mona Bergeron, played by Sandrine Bonnaire, is a woman without a compass, without any purpose other than staying alive and finding small, fleeting pleasures. She may be running from something or someone, but we don’t know. She might have been abused or abandoned, but we don’t know. What we do know is that at the beginning of the film we see that she has died in a shallow culvert, in the middle of winter, in a farmer’s field. We also know that she is fully human, even though her existence is truncated and deeply flawed. She would seem to be free: Free of life’s constraints, life’s worries, life’s responsibilities, life’s burdens.

Mona’s life has become distilled down to the barest rudiments of survival. It would be tempting to think of Mona as merely an animal, as a being without a soul. That would be wrong. Though she may not see it, she is an inherently valuable creature regardless of her history or her choices.

The first shot of the film displays her twisted body in the clean morning light almost as a work of art, nearly as an object. The last shot of the film shows her minutes before she dies, and then fades to black as she cries from deep hopelessness and emptiness. If it does anything at all, Sans toit ni loi strips away our tendency to see Mona as the “other.” She is not an object, or even a subject of investigation. In the film’s final moment she is a person profoundly like me, like you.

This last shot reminds us that, though we might judge her throughout the film, we cannot see her merely as worthless and deserving of her fate. Her final frailty is the frailty of us all. We are all so week, we are all so mortal, and we are all so contingent. For any number of reasons Mona has made a lot of bad choices, but she has done so as a human being, from within her will, not merely from instinct. She may reap what she sows, but in the end don’t we all.

If Citizen Kane‘s moral is banks shouldn’t raise children, then maybe Sans toit ni loi‘s moral is life is hard and freedom is even harder, and total freedom is death. Regardless, though Varda has given us a story that has little plot, and a character who does nothing but wanders aimlessly, yet this film speaks with the voice of the Universe.

The Pagnol/Waters connection: Chez Panisse and the good life

The reason people find it so hard to be happy is that they always see the past better than it was, the present worse than it is, and the future less resolved than it will be.

~ Marcel Pagnol

This post is about dreaming…

Alice Water in early 1970s.

Image by Charles Shere.

If you are a food lover then you’ve heard of Alice Waters. What I had never heard was the story behind the name of her famous restaurant, Chez Panisse. In the forward to the English translation of Marcel Pagnol‘s My Father’s Glory and My Mother’s Castle, Waters writes the following words:

Fifteen years ago, when I was making plans to open a café and restaurant in Berkeley, my friend Tom Luddy took me to see a Marcel Pagnol retrospective at the old Surf Theater in San Francisco. We went every night and saw about half the movies Pagnol made during his long career: The Baker’s Wife and Harvest, taken from novels by Jean Giono, and Pagnol’s own Marseille trilogy—Marius, Fanny, and César. Every one of these movies about life in the south of France fifty years ago radiated wit, love for people, and respect for the earth. Every movie made me cry.

Vahala a.k.a. Chez Panisse

Image by Aya Brackett

She goes on:

My partners and I decided to name our new restaurant after the widower Panisse, a compassionate, placid, and slightly ridiculous marine outfitter in the Marseille trilogy, so as to evoke the sunny good feelings of another world that contained so much that was incomplete or missing in our own—the simple wholesome good food of Provence, the atmosphere of tolerant camaraderie and great lifelong friendships, and a respect for both the old folks and their pleasures and for the young and their passions. Four years later, when our partnership incorporated itself, we immodestly took the name Pagnol et Cie., Inc., to reaffirm our desire of recreating an ideal reality where life and work were inseparable and the daily pace left you time for the afternoon anisette or the restorative game of pétanque, and where eating together nourished the spirit as well and the body—since the food was raised, harvested, hunted, fished, and gathered by people sustaining and sustained by each other and by the earth itself.

This little passage was a revelation for me. I am a fan of Waters and her vision. I love the slow food movement and community supported agriculture (though I need to put by enthusiasms more into practice). I had no idea of her love for Pagnol’s films or how Chez Panisse got its name. Maybe I am the last to know.

A video look at Chez Panisse.

I was searching the library catalog for the films My Father’s Glory and My Mother’s Castle, but the library only had the book, so I checked it out. Originally published in 1960 (in French of course) the Alice Waters’ foreword is from a 1986 edition.

Alice Waters today.

Image by David Sifry.

Two of my favorites things in this world – the kinds of things that makes me say “there is a god” – are great films and great food. I was so pleased to read those words from Alice Waters. Here is someone who is famous for her restaurant, her cook books, her simple, earthy philosophy – all of which I admire – and yet she displays a deeply felt response to cinema. And then she creates a permanent connection between the two great arts. That is the kind of human action of which we need more.

I am now in the hunt for the Marseilles Trilogy (a.k.a. The Fanny Trilogy). I see that is is available on DVD. Since my local library doesn’t have it this might be the final straw that gets me to sign up for Netflix (you’re wondering why I haven’t already). I know very little of Pagnol’s work, but I have a feeling I will love it. I would hazard a guess that he was an interesting individual and a great filmmaker.

The day would turn enchanting when Marcel arrived, unheralded, in the middle of our boring summer holidays in La Treille. From then on, our day was filled with unusual commotion as my brother would immediately stage some activity: long hikes in the hills, picnics, highbrow conversations way off our usual chattering.

~ René Pagnol, Marcel Pagnol’s brother

One day, I saw La femme du boulanger (“The Baker’s Wife”)… It was a shock. This movie is as powerful as a film by Capra, John Ford and Truffaut altogether. Pagnol must have been an outstanding man.

~ Steven Spielberg

Here is a three part homage to Pagnol and the world he inhabited, wrote about, and filmed:

I began this post by saying it was about dreaming. I dream of visiting southern France (where I’ve never been), of making films and writing books (which I’ve only done on the smallest scale), of cooking gourmet meals (which I’ve done many times, but there’s always more), and of eating at Chez Panisse (which I’ve also yet to do). These dreams, and others, keep me alive.

La Chinoise & The Weather Underground

The other day I inadvertently created one of the best double features that I’ve ever seen: First, the fictional narrative La Chinoise (1967) and then, second, the documentary The Weather Underground (2002), based on the revolutionary group of that name.

What makes this double features so powerful? We live in an age where violence against human beings in the name of some cause (religious jihad, war on terror, patriotism, personal peace and prosperity, etc.) is accepted by many generally reasonable people. The U.S. government and TV pundits are currently debating whether torture is okay, or whether certain kinds of torture can be called something else to get around legal requirements. Some argue that extreme force, including the killing of innocent people (collateral damage) in order to send a message (to those who would dare to use violence as a means of sending a message), is an acceptable response to terrorist acts – in other words, matching fatal violence with increased levels of the same.

But does violence work? I suppose it depends on what are one’s goals. In general, though I would argue, violence does not incite peace.

La Chinoise plays out the philosophical debates underlying these issues within a somewhat humorous and heavily symbolic world that might be called godardian. La Chinoise is a fictional tale of what underlies potential violent action, and of political idealism amongst the educated children of the bourgeois. La Chinoise is also considered to have presaged (and possibly encouraged) the student protests in Paris that occurred exactly one year after the film’s release.

The Weather Underground, on the other hand, exposes the reality of those actions and their implications by showing what actually played out in the U.S. In other words La Chinoise says “suppose” and The Weather Underground says “regard.”

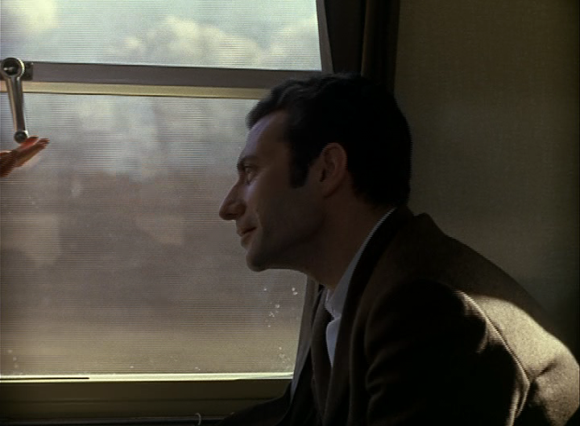

La Chinoise is a kind of remarkable film. I say kind of remarkable because it is also enigmatic and therefore its remarkableness is still very much open to interpretation and evaluation (but isn’t most Godard?). One asks is Godard serious or making fun? Is the film a polemic or a comedy? Is it meaningful or ultimately empty? I can’t say. Many others have done a far better job than I at exegeting the film. But I can say there is one scene I believe is the centerpiece of the film, at least philosophically. That scene is the discussion on the train between Veronique and Blandine Jeanson (playing himself).

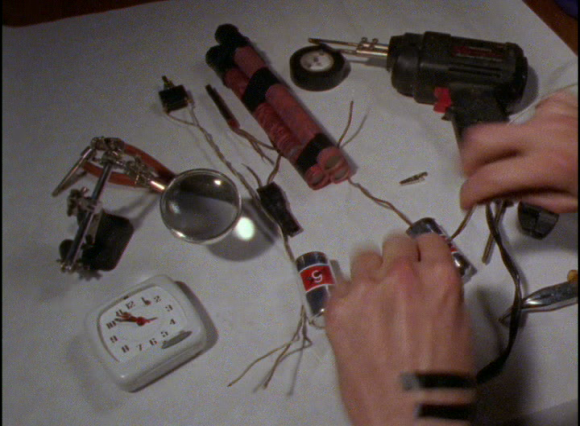

In that scene they talk about the value and implications of using terrorism in the service of a cause. Veronique, and the revolutionary cell of which she is a part, is planning on using a bomb to kill some students and teachers at the university in order to jump-start a revolution. She argues that the bomb will convince others of the seriousness of their cause. Jeanson argues that violence will not produce the results she is looking for. In fact, killing others will only cause everyone to turn against her and her political group.

From my perspective Veronique seems very naive. However, many people felt similarly in the 1960s and early 1970s. I suppose some still do. What would drive a person to such conclusions as Veronique? The Weather Underground explores just such a question.

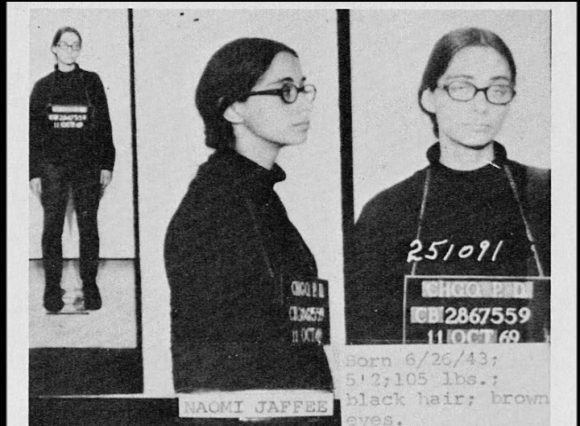

The activist group The Weather Underground began as the Weathermen, a radical outgrowth of Students for a Democratic Society. The film The Weather Underground is a history of that group and the times in which it functioned. It is one of the best documentaries I have seen.

What drove the Weathermen was a desire to change the world. Frustration in the slowness of change, and even the continued deterioration of certain concerns (such as the escalating war against the Vietnamese), gradually led the group down the path toward violent action.

Much of the film includes interviews with former members of the group. It is fascinating to hear them describe what choices they made, why they made those choices, and what they think of them now. There is a lot of regret for some of the former members. In a sense the film pulls back the romantic veneer of the 1960s anti-war movement and shows a more realistic complexity. What we get is something that makes La Chinoise appear to be both more profound and more like a cartoon of itself.

>vive la commune | vive la vérité

>

Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.

~A. J. Liebling

One of the most fascinating and important scenes in Watkins nearly 6 hour (the shortened version) masterpiece La Commune (Paris, 1871) is when the established press (print) discusses with the burgeoning Commune TV* crew about the nature and goals of journalism. They argue over the nature of television news and its relationship to the worker’s uprising and the establishment of La Commune de Paris (the temporary socialist/anarchist government that ruled Paris in mid 1871).

The question on the table is why the television team doesn’t dive more deeply into the issues and, in particular, focus on the debates raging within the new government about its policies and procedures. The short answer is that serious debate just isn’t appropriate to the nature of television. This is the same concern we have today.

At its inception Commune TV was all enthusiasm. They had taken/stolen some television equipment and started covering the revolution like some community television crew – great ebullience and limited technical knowledge.

Here the two reporters, male and female (as apposed to the single male reporter for national television), introduce themselves. Alongside them stands a representative of the revolutionary press.

Commune TV gets many of its ideas from the press. In some ways they become a kind of mouthpiece for the revolutionary newspapers, but they also back away from getting too deep into the issues. Their goal is to primarily give voice to the citizen revolutionaries. So they provide lots of individuals’ opinions and talking heads without a lot of organization.

The national television station provides the “official” perspective on the revolution. This perspective represents the traditional bourgeois and ruling class interests. Its format and style is much more professional and apparently reasonable, conveying ideas and perspectives in a droll monotone as though they are merely unarguable facts.

And here is the scene in which the revolutionary press argues with Commune TV about how they cover the revolution and why they don’t present some ideas critical to the raging debates about the new government and its direction.

The answer given by Commune TV is essentially two parts, 1) They don’t want to cover anything that isn’t import, thus censoring their coverage based on what they like and don’t like, and 2) They don’t like long, drawn out debates, rather they like short, exciting pieces that keep people interested. In this way Commune TV provides a kind of in-the-trenches, embedded revolutionary news while following some of the assumptions of the national news about the television medium itself. Thus, what we find is that both the national television news and the commune’s television news provide limited and distorted perspectives on what is happening.

La Commune (Paris, 1871) is a remarkable film. It is a far more important film than its largely unknown status might indicate. It will never be widely popular because it does not fit the mold of popular films, but it is both mesmerizing and challenging. By raising the questions of what is the role of news and, in particular, what is the role of news in a time of revolution (war), this film calls us to re-evaluate the present. We are in a time of revolution. There are those today who, with unprecedented corporate power and military might, are seeking to shape the world according to imperialistic philosophies of power. This is truly revolutionary. And the mainstream media plays along. I would argue that we need another revolution, one that is not based on imperialism, “might equals right”, corporate greed, or nationalistic patriotism – even if the words freedom or democracy are attached.

If this is brought up in polite conversation many will say, “I just don’t see it.” At least that has been my experience. But we are often like fish in water when it comes to our own culture. I think of it like the visual puzzles that look like one thing, but if you stare long enough, and maybe with someone guiding your vision a little, you begin to see the “buried” image hidden within. Look behind our popular media and you will find amazing and troubling things.

That is why I like Democracy Now.

Amy Goodman and Juan Gonzalez of Democracy Now.

Democracy Now is just one outlet, but a great one for alternative news, and this is not an endorsement, just a statement of fact. Other outlets include The Guerrilla News Network and Truthdig.

What then is the role of independent news? The following video is one of the most powerful examinations of how the media and the Iraq war have and continue to go together like hand and glove. Without an independent media, without other sources of news, how are we to know what is really going on in the world? How are we to realize that when we think we understand even the basics we too easily don’t?

http://video.google.com/googleplayer.swf?docid=-6546453033984487696&hl=en

*Just in case your were wondering, television had not yet been invented in 1871. Watkins uses this creative device to draw comparisons with that era and ours, and the to highlight the relationship of news media to truth.