The other night I introduced my daughters to the film version of West Side Story (1961). In so many ways this is a great film, not least of all because it is a great American sociological document of sorts. The story revolves around the big gang fight, or rumble. Everything leads up to it and then reacts to it. The rumble is not only the central event, but it also contains the key defining moment. That moment is the movement from wanting peace to using violence – the quintessential movement that produces the “how could this have happened” scenario.

Here’s how it plays out: The two gangs, Sharks & Jets, meet under the overpass to fight it out. What they are fighting about is really anyone’s guess – territory, honor, hormones, it’s hard to tell. Tony (a.k.a. Romeo), the former leader of the Jets, but now a guy with a job and a love interest (Maria, a.k.a. Juliet), shows up just as the rumble is getting started. He tries to stop the fight. He pleads, pushes gang member apart, gets mocked and hit, but to no avail.

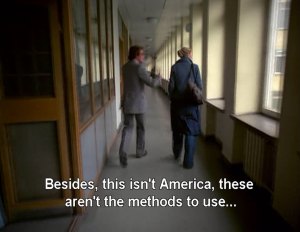

Here he pleads with Bernardo, the Sharks’ leader, to stop the rumble:

Bernardo has no interest in not fighting. He is there to fight. He calls Tony chicken. Tony is not phased by this. He lets the others mock him, but he cannot let them fight. But then, as Tony tries to keep Ice from fighting Bernardo, Riff strikes Bernardo in the face. The knives come out. Then Riff gets stabbed and killed by Bernardo. Tony, in a moment of rage, picks up the knife and lunges at Bernardo.

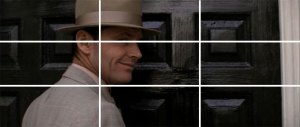

With almost identical angle and framing we go from an image moments earlier (the shot above) of attempted reconciliation to this moment on rage and murder:

What happened in those few moments between these two shots? How could Tony have gone from seeking peace to vengeful murder in less than three minutes? What caused this movement from peace to violence? One answer is that peace was fundamentally foreign to him. In his life he had gone from being a young man of violence as the leader of the Jets to a slightly older, but still young lowly worker in the same neighborhood. But it’s not just that his environment has not changed much. He hasn’t really changed much. Although his job had begun to civilize him a bit, his problem is that he has not consciously sought peace, or a life of peacefulness, until a girl enters his life. Love is a strong motivator for many things, but not enough to overcome deeply ingrained habits on such short notice.

Practicing peace is a conscious effort to form new habits as well as to engage one’s mind towards peaceful solutions. We not only live in a violent world, but we Americans are trained by our culture to think and behave violently. Our culture provides us with constant justifications for using violent means to “solve” our problems and deal with our enemies. Our country was formed through bloodshed, slavery was overcome through bloodshed, the Westward expansion was accomplished through bloodshed, and it goes on and on. We call heavily armed soldiers paroling the streets of other people’s countries “peacekeepers.” Our nuclear arms policy is “mutually assured destruction.” We believe we can establish democracy in various parts of the world at the end of a gun. These things are reported daily by our popular news outlets and rarely do we cringe. To live in such a world will inevitably train us into people who consider violence a normative option for achieving our goals. Violence is always “on the table” as our politicians are fond of saying – and it’s as old as Cain and Able. It doesn’t take much to encourage and reinforce the violence that is already in our hearts.

Peace is not a state of being as much as it is a way of life. Peace takes courage and creativity. The tragedy for so many people is that peace is something one hopes for after the dust has settled. But peace is not some languid, passionless rest. Peace is the activity of loving our neighbors as ourselves, of loving our enemies, of being servants, and of holding each other accountable. In a violent world peace requires thinking out of the box, out of bounds, charting unfamiliar territory, and being willing to keep asking questions that seem to have already been answered. Peace is something we need to practice everyday, both for today and for tomorrow. Tony did not practice peace and was unprepared at the moment he most needed a creative solution. More than that, he had not been working toward peace in his neighborhood all along. He had no foundation, no authority.

There is a moment late in the film when Doc asks the Jets, “When do you kids stop? You make this world lousy.” And one of the Jets replies, “We didn’t make it, Doc.”

This line could be seen as an indictment of our society. In other words, how else could or should these kids behave when the world given to them is so lousy? But Doc, rather than being silent at that moment, could have answered, “No, we all make this world. With every choice and every action you are making this world just like the rest of us in this neighborhood. You can choose peace or violence, love or hate, but whatever you choose and whatever you do, you are making this world too.” Doc’s lack of a proper response indicts him as well in this mess. The real tragedy of West Side Story is the profound lack of wisdom from every character.

Using West Side Story to discuss the concept of practicing peace may seem a bit strange. West Side Story is a big , colorful, sappy, song and dance spectacle. It is nearly fifty years old and in many ways it is dated, though still a great evening of entertainment. However, sometimes watching films that are outside our own period make it easier to see what is going on. Storytellers rely on conflict to drive a story forward. In fact, I cannot think of a single film that does not have conflict somewhere in the story. Audiences lose interest quickly if there is no conflict. More than that, if there is great conflict with stunning violence and massive destruction, audience flock to the theaters. In West Side Story it is easy to think these characters should just get over it, move on, get jobs. It is easy to ask what is wrong with these kids, why don’t they stop fighting? But in films of our own period (think of all the blockbusters of the last ten years) it can be more difficult to see because we are enjoying them so much.