We used to be in the Christian Classical Home Schooling Movement. We home schooled our three kids until they moved over to public high school. I wrote the article below in 2011. I think it still holds up. In fact, as I re-read it today, I feel convicted. I need to follow the great saint’s teaching myself. I don’t so much of the time.

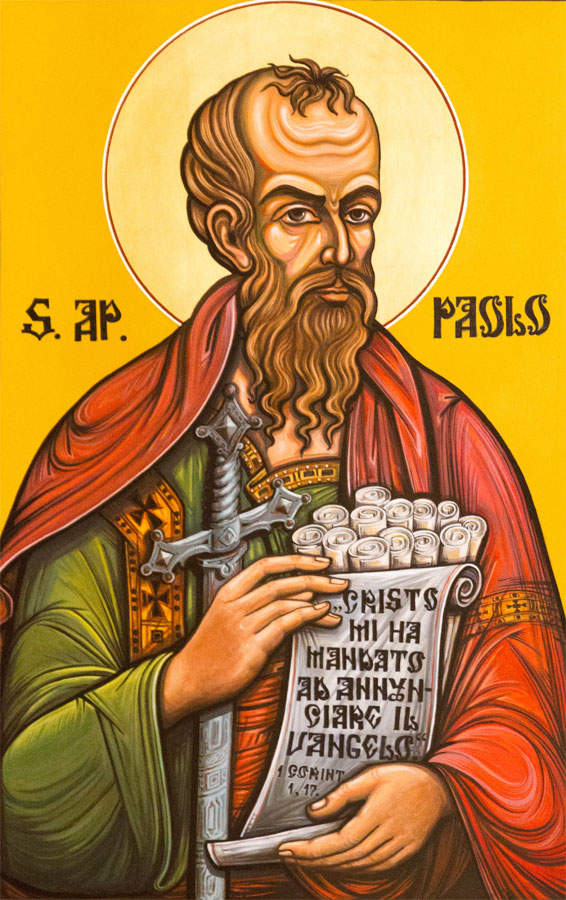

I do not know if Saint Paul ever developed a detailed educational foundation or curriculum or program in the way that we might today. He may have in person as he spread the Gospel, but he certainly didn’t in his letters. And I doubt he ever founded a school (of course, if he did he would not have needed to use the word “classical” in its name). I guess that for Paul “starting” this thing we call Christianity was enough to keep him busy and get him killed (of course he didn’t start it but he was a laborer laying the foundation). But still, as I ponder what Christian Classical Education is or might be, I wonder what Paul would contribute. Without trying to turn this into an overwhelming project for which I am unprepared, I want to briefly look at only a couple of verses from Paul’s letter to the church at Philippi. He writes in Philippians 4:8-9:

Finally, brothers, whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is commendable, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things. What you have learned and received and heard and seen in me—practice these things, and the God of peace will be with you. (ESV)

Consider this list:

- What is true

- What is honorable

- What is just

- What is pure

- What is lovely

- What is commendable

- What is excellent

- What is worthy of praise

What do we do with such a list? Imagine going to your local school board and proposing that the district’s curriculum be revamped to begin with this list. Ha! I dare you.

Paul says to think about these things.

To think. In the minds of our modern educators, and most of the rest of us, thinking is almost tantamount to doing nothing. Ever see someone thinking? What are they doing? On the outside they are often quite still, maybe staring into the distance. In effect, they are doing nothing. And yet, they are doing a great deal. Now, if they are not thinking alone, staring placidly off into space, then they are probably in dialogue with someone. But a true dialogue can seem to be unfocused and wandering, which is also antithetical to teaching in the modern sense. Our modern education system is partially based on a sense of urgency–we cannot afford to waste time with thinking when we have so much knowledge to get into those little brains. It is a system that must swap dialogue with lecture. But this modern system denies the existence of the human soul. Is that what we want?

Paul says to think about these things.

What is thinking? I know nothing about the brain as a subject of scientific study. I know there are chemicals and electrical impulses involved, but more than that? I know nothing. However, I gather thinking is a mystery of our minds, of our humanity. I use the word mystery because I doubt science can ever, truly plumb the depths and workings of thinking. Thinking is a mystery because it is a force of great power that seems to have no substance, no true existence, no way to completely contain it and control it as a totality. We can guide it, use it, encourage it, welcome it, and share it, sometimes even fear it, but we cannot subdue it. To think is to ponder, to wonder, to suppose, to engage, to meditate. More importantly, thinking is to take an idea into oneself, into one’s soul, and turn it over and over and make it one’s own, or to reject it in favor of another.

So then we ponder and wonder, suppose and engage, meditate and bring into one’s soul

- What is true

- What is honorable

- What is just

- What is pure

- What is lovely

- What is commendable

- What is excellent

- What is worthy of praise

Can you think of any better education? I can’t.

Paul could have left it there, but he goes on. He writes, “What you have learned and received and heard and seen in me…” Consider this, Paul is able to confidently write that the Philippians have directly experienced him in such a way that they have:

- learned from Paul

- received from Paul

- heard from Paul

- seen in Paul

This list is somewhat cryptic, but I think we can get a glimpse into how Paul was a teacher. First the Philippians learned from Paul. He saw himself as a teacher. He had intent. He knew what he wanted to teach them. And he taught them thoroughly enough, with enough feedback, to know that they leaned. Then he says they have received. This implies a giving, a handing over. There was something that he left with them, something they now have. He can write to them because he knows they have what he gave. In this sense they are more like Paul than they were before. The goal of the classical educator is that his pupils will one day become his colleagues. The Philippians are now that much closer to being colleagues of Paul; they have something that Paul has. Third he says they heard from Paul. Teaching often involves speaking and hearing, but sometimes we forget what a gift is language. If you are like me then you love Paul’s letters, but you would really love to hear him speak, to ask him questions, to sit at his feet. Paul engaged their minds as God intended, as their minds were designed to function, by using language. Speaking also requires presence. Paul was with the Philippians, in person, in the flesh; they heard his voice, knew its sound, picked up on nuances of meaning in the subtleties of his voice. To hear in this way, that is to listen to ideas spoken, is a profoundly human experience. We do not know if the Philippians heard Paul specifically because he preached, or perhaps led them in Socratic dialogue, or even just through conversation, but they heard. Finally, and this may be the most important, they saw. Paul presented himself as an example. He lived what he taught. Or better yet, he embodied the Logos. The Gospel, the message, the content that Paul taught, handed over, and spoke, was also visible in his life and actions. Paul could rightly say, “look at me.” The best teachers embody the logos.

Can we find more about how Paul taught? Yes, I’m sure we can. But just from these two verses we get something profound. We find that Paul, with confidence, can say the Philippians

- learned from Paul

- received from Paul

- heard from Paul

- saw in Paul

And what did they learn?

- What is true

- What is honorable

- What is just

- What is pure

- What is lovely

- What is commendable

- What is excellent

- What is worthy of praise

From this alone we can know that Paul was a master teacher in the fullest Christian Classical model. How this will look in your own teaching will be unique, but there is no better foundation that I can find.

And then Paul writes:

“…practice these things…”

Paul both taught in person and was writing to the Philippians with an Ideal Type in mind, that is the complete or perfect Christian, that is Christ. Christ is the logos. We, because we are Christians, because we are disciples, seek to embody the Logos in our lives. It is not enough to find the idea of the Ideal Type good or fascinating or excellent. One must put it into practice and live it. To practice is to work and persevere at imitation. To imitate is to behold, to embrace, to take into one’s being and seek to embody the Ideal Type in one’s life and actions.

David Hicks wrote: “To produce a man or woman whose life conforms to the Ideal in every detail is education’s supremely moral aim.” (Norms and Nobility, p. 47) Is this not also the passion of Paul, that the Philippians live’s would conform to the Ideal of Christ in every detail? And how are the Philippians to do this?

“…practice these things…”

Now, if you haven’t noticed, I have not defined what Christian Classical Education is or how to do it. Partly this is tactical; I don’t have a clear answer. On the other hand I will offer a quote from Andrew Kern:

Education is the cultivation of wisdom and virtue by nourishing the soul on truth, goodness, and beauty so that the student is better able to know and enjoy God.

I cannot think of a better, more fundamental description of what a Christian Classical Education is all about. There is a lot in there, and a lot of room for developing strategies of teaching, but if this is what we are aiming for, if this is what we are building on, if this is our longing, then consider again the words of Saint Paul:

Finally, brothers, whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is commendable, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things. What you have learned and received and heard and seen in me—practice these things, and the God of peace will be with you.

Do that and the God of peace shall be with you.