>

“The earth is blue. How wonderful. It is amazing.”

~ Yuri Gagarin to Ground Control, 1961

Lately I’ve been going back to some classic science fiction writing. I started Asimov’s Foundation, Heinlein’s Have Space Suit–Will Travel, and Bradbury’s R is for Rocket.

Here is Isaac Asimov remembering

the Golden Age of Science Fiction:

I am convinced if there had to be a golden age of science fiction it had to be exactly when it was, in the couple decades prior to actual space travel. Technology had developed, because of WWII and the Cold War, to such a degree that many of the far fetched fantasies of earlier years now seemed almost plausible. And yet no object had yet been put into orbit or sent to another planet, and certainly no human had entered space. With this situation of having technology’s promise so close and yet so far it is no wonder the imaginations of so many were fueled in that direction. Once Gagarin orbited Earth the golden age had little time left. That had a lot more to do with the appearance and disappearance of sci-fi’s gold age than an emphasis on the rise of pulp magazines, etc.

And as a special bonus…

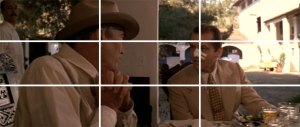

You know you’ve arrived as an author when you can get paid doing prune commercials.